- Speaker: Rich Hickey

- Event: New York City Java Special Interest Group meeting - June 2008

- Video: Part 1: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=P76Vbsk_3J0 Part 2: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hb3rurFxrZ8

[Editor's note: I have included the original code examples from the talk. In a very few places, there are editor marks in square brackets that also give the modern versions, if the ones in the talk did not work with Clojure 1.10.1, the latest as of 2019. There are very few examples of this, and it appears that the syntax changes were made before Clojure 1.0 was released in 2009, after this talk was given.

This page says the presentation was given in June 2008: https://github.com/tallesl/Rich-Hickey-fanclub

That date fits with a mention in this talk of another talk Rich Hickey planned to give later in Europe at the ECOOP workshop, whereas in September 2008 when he gave his "Clojure for Lisp Programmers" talk, he mentioned giving the ECOOP talk earlier. ECOOP 2008 was held July 2-11, 2008.]

[Time 0:00:00]

slide title: Clojure

A Dynamic Programming Language for the JVM

An Introduction for Java Programmers

Rich Hickey

Hi. I am Rich Hickey. I am here to talk about Clojure, which is a programming language I wrote for the JVM.

This particular talk is oriented towards people who program in Java or C# or C++. In particular, I am not going to presume any knowledge of Lisp. So you might find some of it tedious, although I am preparing for a talk I am going to give at ECOOP to the European Lisp Workshop, where I am going to talk about the ways Clojure is a different Lisp. So maybe some of this will be interesting to you in that respect.

[Time 0:00:45]

slide title: Introduction

+ Who are you?

+ Know / use Lisp?

+ Java / C# / Scala?

+ ML / Haskell?

+ Python, Ruby, Groovy?

+ Clojure?

+ Any multithreaded programming?

But that is the nature of this talk. It is going to be an introduction to the language, a fly-by tour of some of the features. I will drill down into some of the others.

I started to ask this question before, but I will just ask it again to sort of see. Is there anyone here who knows or uses any flavor of Lisp? Common Lisp, Scheme, or Clojure? OK, so mostly no.

I presume a lot of Java, or anything in that family: C++, C#, Scala anyone? You must be playing with it, right?

How about functional programming languages like ML or Haskell, the strict guys? Anyone? A little. You do not really want to raise their hands about that one. OK. That is good. In particular, I think coming from that background, you will understand a lot of this straight away.

How about dynamic programming languages: Python, Ruby, or Groovy? Yes, about half.

And I asked before: Clojure? And we have a few people with their toes in the water.

The other key aspect of Clojure that would matter to you if you are a Java programmer is whether or not you do any real multi-threaded programming in Java, or in any language. Yes? So some.

[Time 0:02:01]

So you use locks, and all of that nightmare stuff.

I am a practitioner. I have programmed in C and C++ and Java and C# and Common Lisp and Python and JavaScript and a bunch of languages over the years.

Way back, this same group, I think it is the same lineage, was the CSIG. And when I first started to come, I started to teach C++ to the CSIG. And it became the C++ and CSIG, and eventually the C++ and Java SIG, and now the Java SIG. So back in the 90s, early 90s and mid 90s, I taught C++, and advanced C++ to this group, and ran study groups. And I have come back tonight to apologize for having done that to you, and to try to set you off on a better track.

[SIG is probably an abbreviation for Special Interest Group]

[Time 0:02:59]

slide title: Agenda

+ Fundamentals

+ Syntax and evaluation model

+ Sequences

+ Java Integration

+ Concurrency

+ Q & A

So we are going to look at the fundamentals of Clojure, and it will be also of Lisp in many ways, but I am going to say Clojure. Do not take offense. All of these things, or many of the things, I say are true of Clojure are true of many Lisps. I did not invent them. They are not unique to Clojure. But some things are.

Then we will look at the syntax and evaluation model. This is the stuff that will seem most unusual to you if you have come from a compile, link, run language, and one of the curly brace, C derivees, like Java.

Then we will look at some aspects of Clojure, sequences in particular, and the Java integration, which I imagine will be interesting. And I will finally end up talking about concurrency. Why Clojure has some of the features it does, and how they address the problems of writing concurrent programs that run on the new, and indefinitely -- for the indefinite future, multicore machines.

[Time 0:04:05]

And I will take some questions. At some point in the middle, we will probably take a break. I do not know exactly where that is going to go.

[Time 0:04:10]

slide title: Clojure Fundamentals

+ Dynamic

+ a new Lisp, not Common Lisp or Scheme

+ Functional

+ emphasis on immutability

+ Hosted on the JVM

+ Supporting Concurrency

+ Open Source

So what are the fundamentals of Clojure? Clojure is a dynamic programming language. And dynamic has a lot of different meanings. In particular, it is dynamically typed. That would be an expectation you would have of Python or Ruby or Groovy. It achieves that dynamic nature by being a Lisp, and I will talk more about that.

I do not see a lot of people who know Lisp here, but that does not mean there is not a bias against Lisps. I mean, how many people have seen Lisps and said: Oh, my god! Ugh! I cannot believe the parentheses.

And I would say: I would hope you put that bias aside for the purposes of this talk. It ends up that for people who have not used Lisp, those biases have no basis, and for most people who have given it a solid try, they vanish. And in fact, many of the things that you consider to be problems with Lisp are features, down the line.

But having said that, Clojure is a very different Lisp. It is syntactically much leaner than a lot of Lisps. It has fewer parentheses. It uses more data structures in its syntax, and as a result, I think is more succinct and more readable. So it may be the time to try Lisp again.

Another aspect of Clojure is as a functional programming language. And again, I am going to talk in detail about these things. For now you can just say that means a focus on immutability in your programs, to write programs primarily with immutable data structures. And if you are coming from another Lisp, this will be an area where Clojure is definitely different. I made different decisions about the data structures in Clojure.

[Time 0:06:05]

The third leg of Clojure -- it sort of stands on four points. It is dynamic. It is functional. It is hosted on the JVM, and it embraces the JVM, its host platform. There are ports of other languages that sort of just sit on the JVM. There are ports of, for instance, Common Lisp that sit on the JVM, but they do not really connect very well. For a number of reasons. One is: they are implementing a standard. The standard was written before Java was written, and there is just no merging the type systems.

On the other hand, Clojure was written for the JVM, and so it is very heavily integrated with it. So not only does it reside there, which is a benefit because you can run it if that is your environment, but it embraces it, which means the integration is good, and it is pretty transparent to go back and forth.

The fourth aspect of Clojure is the concurrency aspect. I work in C# with guys writing broadcast automation systems. They are multithreaded. They have all kinds of nasty stuff going on, multiple connections to sockets, lots of databases, data feeds from all kinds of places.

And it is not fun writing programs like that, that need to share data structures amongst threads, to have them get maintained over time, and have everybody remember what the locking model is. It is extremely challenging. Anyone who has done any extensive multithreaded programming with the locking model knows how hard it is to get that right.

So Clojure is an effort on my part to solve those problems, in an automatic way, with language support.

And the last thing is, it is an open source language. It is very transparent, the implementation, and everything else is up there for you to see.

[Time 0:07:55]

slide title: Why use a dynamic language?

+ Flexibility

+ Interactivity

+ Concision

+ Exploration

+ Focus on your problem

We started to talk about this before. Why use a dynamic language? Some people are very happy. Of the people who are programming in Java, how many are happy about that? They like Java. They have no complaints. OK. Not too many.

It ends up that, I think, many Java programmers look at people who are using Python, or Ruby, and being very productive, and I think, justifiably, envy their productivity, the succinctness, the flexibility they have. And in particular, how quickly they can get things done.

And it ends up that that is a fact of the static languages, especially the ones like Java, that they are inherently slower because of the amount of, well some people call it ceremony, that you have to go through to communicate with the language. It slows you down.

So flexibility is a key thing you would look for in a dynamic language. Interactivity is another key point. Again, this goes back to Lisp. Lisp has pretty much always been an interactive language. And that means a lot of things. In particular, it means that when you have got a Lisp up and running, you feel like you are engaged with an environment, as opposed to shoveling your text through a compiler phase to produce something else out the other end.

So that interactivity is kind of a deep thing. The REPL is part of it. That means Read, Eval, Print, Loop, and I will talk about that in detail in a little bit.

Dynamic languages tend to be a little more concise. That does not mean that static languages cannot be. Haskell, in particular, is very concise. But the curly brace languages are not concise. Java is probably a great example of a language that is not concise.

And that is not just a matter of tedium. It is a matter of where is your logic? How far apart is your logic? How spread out is it? Can you see what you are thinking about, or is it in pieces? Is it spread out by a bunch of things that are not about your problem?

[Time 0:10:00]

Dynamic languages are definitely more suitable for exploration. There is a certain aspect in which static languages are like concrete. That is a good aspect when you are trying to finish. In some systems, concrete is going to be more resilient. It is more resilient to change. It is more structured, and it is rigid.

On the other hand, that is not necessarily the kind of materials you want to be working with when you are trying to figure out what your structure should look like in the first place. So dynamic languages are better for exploration.

And in particular what I like about dynamic languages, and Lisp, fundamentally, and I think in a way that other languages do not achieve, is it lets you focus on your problem. You can, with Lisp, and its ability to do syntactic abstraction, suck everything out of the way, except the problem. And for me, when I discovered Lisp, I was a pretty expert C++ programmer, I said to myself: What have I been doing with my life? It was that big a deal.

[Time 0:11:14]

slide title: Which dynamic language?

+ Many options on the JVM

+ allow you to leverage your existing knowledge and code

+ Ports to JVM

+ JRuby

+ Jython

+ Native to JVM

+ Groovy

+ Clojure

So there are many dynamic languages. I am going to talk about Clojure. And I will not do bashing of other languages, but I will try to highlight why you might choose Clojure over some of the other options, because in particular now I think it is a great thing that there are many dynamic languages available for the JVM, and dynamic languages are supported as a concept in the Java community.

You know, at Java One there were plenty of presentations on Jython and JRuby and Groovy, and these other languages. And Sun has hired some of the developers of these languages, and given it kind of official support as something that is viable to do on the JVM. So you are going to see mixed language programming being accepted in Java shops.

[JavaOne https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/JavaOne]

[Time 0:12:01]

So how do you pick? I think you can categorize languages in one dimension pretty straightforward. Are they a port of a language that exists somewhere else, or were they written for the JVM?

Ports have a bunch of challenges. One is: there is a canonic version out there, because most of these languages are not defined by a specification. They are defined by a canonic implementation. So there is CRuby. There is CPython. Those are, really, the languages. And the other things are ports, which have to struggle to follow along with the C version.

The other problem ports have is: a lot of the infrastructure for the languages, especially the ones that do not perform very well, are written in C. In other words, to get the library performance they need, the support libraries for Python are written in C. So an effort to port Python to Java means having to replicate those C libraries. So there is that.

I would say the main appeal to a ported language is: if you already have an investment in Ruby, or Python, or you happen to really love the language designs, that is a good way to go here.

I would say if not, if you are just starting from scratch, you may find that a language that is native to the JVM is going to give you better integration. You know the version you are using is the canonic version. The canonic version of Groovy is the JVM language. The canonic version of Clojure is the JVM language.

And I would say of the two, Groovy is going to let you do what you do in Java, except a little bit more easily. Fewer semicolons, more dynamic, there are some builders, there are some idioms, there are closures. Sort of the fun of dynamic programming, and a lot of the similar syntax, to Java. So I think if you are just interested in dynamic, and want to continue to write programs that are like your Java programs, Groovy cannot be touched.

[Time 0:14:00]

Clojure is not about writing programs like your Java programs. Clojure is about realizing what is wrong with your Java programs, and doing something different. So you will find some of that through the talk.

[Time 0:14:15]

slide title: Why Clojure?

+ Expressive, elegant

+ Good performance

+ Useful for the same tasks Java is

+ Wrapper-free Java access

+ Powerful extensibility

+ Functional programming and concurrency

So Clojure itself, it inherits from Lisp an expressivity and elegance I think is unmatched. Depending on your mind set, you may or may not agree, but there is a certain mathematical purity to lambda calculus, and the way it is realized in Lisp, the uniformity of the syntax, is elegant.

Clojure also has very good performance. Again, I am not going to get involved in any language bashing, but I am pretty confident no other dynamic language on the JVM approaches the performance of Clojure in any area, and is unlikely to. But everybody is working on performance.

[Audience member: Can I interrupt you just for a second?]

Certainly.

[Audience member: The thing that you hear tbd]

We have converted them. They are Java programmers now.

[Audience member: tbd]

So the performance is good. I made a point before starting the talk that an objective of Clojure is to be useful in every area in which Java is useful. That you can tackle the same kind of problems. I do not write web apps, and put stuff in and take it out of the database kind of applications. I write scheduling systems, broadcast automation systems, election projection systems, machine listening systems, audio analysis systems, and I write them in languages like C# and Java and C++. And Clojure can be used for those kinds of problems.

[Time 0:15:55]

It does not mean that it cannot also be used for web apps, and people did that right away with Clojure, and database and UI stuff. But it has that same kind of reach. And one of the nice things about Java is it has a wide range.

Clojure has direct wrapper-free access to Java. Some of the ported languages have to use wrappers, because those languages have their own object systems that imply a bunch of dynamic features that they have to glom on top of Java objects when you interoperate with them. Clojure was designed to provide direct access to Java. It looks like Clojure, but it is direct.

Clojure, being a Lisp, is extensible in a deep way, and we will talk a little bit more about how you get syntactic extensibility through macros.

And then Clojure, I think, is completely unique amongst the languages on the JVM in promoting immutability and concurrency, much more so than even Scala, which is often talked about as a functional language, but is not deeply immutable. It sort of is an option. Clojure is really oriented towards writing concurrent programs, and immutability for its other benefits outside of concurrency.

[Time 0:17:19]

slide title: Clojure is a Lisp

+ Dynamic

+ Code as data

+ Reader

+ Small core

+ Sequences

+ Syntactic abstraction

So how does Clojure get to be these things? It is a Lisp. Again, put what you think about Lisp aside. I will explain what that means in depth as I go into each of these points. But Lisp in general is dynamic in that way, interacting with an environment, having a REPL, having introspection capabilities on the environment, being able to modify things in a running program, are all characteristics that make it dynamic.

A fundamental feature of all Lisps, if they want to be a Lisp, is that code is represented as data. And again, I will explain that in detail.

[Time 0:18:00]

There is a reader, which is part of the implementation of "code is data". It is sort of something in between your text and the evaluator.

Being a Lisp means having an extremely small core. You will find, when you contrast Clojure to other languages, even languages that are theoretically light weight like Python or Ruby, Clojure has way less syntax than those languages. Far less complexity, in spite of the fact that they appear easy.

Lisps generally have tended to emphasize lists. Clojure is not

exactly the same way. It is an area where Clojure differs from Lisps

in that it frees the abstraction of first and rest from a data

structure, the cons cells. And in doing so, offers the power of Lisp

to many more data structures than most Lisps do. So there is that

sequence thing, and I will talk more about that in detail.

[More on cons cells, and the function named cons that exists in

Lisps, including Clojure: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cons]

And syntactic abstraction. Again, we have abstraction capabilities with functions or methods in most languages. Lisps take that to the next level by allowing you to suck even more repetition out of your programs, when that repetition cannot be sucked out by making a function.

[Time 0:19:22]

slide title: Dynamic development

+ REPL - Read-eval-print-loop

+ Define functions on the fly

+ Load and compile code at runtime

+ Introspection

+ Interactive environment

OK. So we will dig down a little bit more. What does it mean to do dynamic development? It means that there is going to be something called a REPL, a Read Eval Print Loop, in which you can type things and press enter, and see what happens. I guess we should probably do that.

[Screen switches from slide to a Mac desktop with some windows open,

one with a file test.clj containing Clojure code, another containing a

REPL prompt user=>.]

So this is a little editor. It is kind of squashed in this screen

resolution, but down below is the REPL. This is Clojure in an

interactive mode, and we can go and we can say (+ 1 2 3) and we get

6.

[Time 0:20:00]

We can do other things Java-like. I will show you some more of that

later. But the general idea is that you are going to be able to type

expressions, or in your editor say "please evaluate this". I mean I

can go up here to (. Math PI) and hit the key stroke that says

"evaluate this", and you see below we get that [3.14159265...].

And that is kind of what it feels like to develop. I am going to show you even more after I explain what you are looking at, because I do not want this talk to be yet another where people are shown Lisp, not having had explained to them what they are looking at. So we are going to do that first.

But you have this interactive environment. You can define functions on the fly. You can fix functions on the fly. You could have a running program, and fix a bug in a running program. And that is not like being in a mode in a debugger where you have this special capability to reload something. It is always present. If you build an application with some access to the ability to load code, either a remote REPL connection, or some way to do that, your running production systems will have this capability to have fixes loaded into running programs.

In general, there is not the same distinction between compile time and run time. Compiling happens all of the time. Every time you load code, every time you evaluate an expression, compilation occurs. So that notion of phases of compilation is something you have to relax when you are looking at a language like Clojure, and I will show you the evaluation model in a second.

I talked a little bit about the introspection, but that is present. You are sitting at a REPL. Clojure is there. Clojure has namespaces. You can get a list of them. Clojure has symbols. You can get a list of those. You can look inside the infrastructure that underlies the run time, and manipulate it.

And that is what I mean by an interactive environment. I just do not mean typing things in. I mean there is a program behind your program. That is the run time of Clojure, and that is accessible.

[Time 0:22:03]

slide title: Atomic Data Types

+ Arbitrary precision integers - 12345678987654

+ Doubles 1.234 , BigDecimals 1.234M

+ Ratios - 22/7

+ Strings - "fred" , Characters - \a \b \c

+ Symbols - fred ethel , Keywords - :fred :ethel

+ Booleans - true false , Null - nil

+ Regex patterns #"a*b"

If I say something that you do not understand, you can ask for clarification.

I am endeavoring to try to come up with the ideal way to explain Lisp

to people who have never seen it, and this is what I have come up

with, which is to talk about data. Lots of languages have syntax.

You can talk about Java, you can talk about "here is main", and here

is what public means, and static, and then you can dig in to

arguments to a function and things like that.

But we are going to start here with data. In particular, data literals, and I think everybody understands data literals from the languages they are familiar with. You type in "1234", and you know that is going to mean one thousand two hundred and thirty four to your program.

So Clojure has integers. They have arbitrary precision. They can get as large as your memory can support. And the promotion of small integers to larger integers while arithmetic is going on is automatic.

[TBD: This is somewhat nuanced in modern Clojure as of 2019. Good to have very brief explanation, or better a link to one, here.]

It supports doubles as the floating point format. Those are Doubles.

Those are big D Double Java doubles, when you type them in.

[Audience member: tbd]

Right. They are Java doubles. But they are the big D doubles. So one of the things you are going to see about Clojure is: everything is an object. All numbers are boxed, at least until you get inside a loop, where I can unbox them. But it is a language in which numbers are boxed, unlike Common Lisp, where you have access under the hood to use tagged integers and tagged numbers, which is more efficient in allocating them on the heap, no capability of doing that in the JVM.

There has been talk about it, them adding it [developers of the JVM itself], which is stunning to me. Apparently the guy, there is this guy John Rose at Sun who really does understand Lisp very well,

[Time 0:24:00]

and has talked about all kinds of really neat features, which if they make it into the JVM would make it stunning. Like tail call elimination and tagged numbers.

But in the absence of that, numbers are boxed, so that everything can be an object, and can be treated uniformly.

You have BigDecimal literals. You have ratios. 22 over 7 is

something, it is not divide 22 by 7. It is a number. It is a number

that is not going to lose any information, versus dividing 22 by 7 and

either truncating or converting it to a floating point format where

you will lose information. So ratios are first class.

String literals are in double quotes. They are Java strings. Same thing, immutable. No conversions. No mapping. Again, being a native JVM language means I can just adopt the semantics of Java literals. I do not have to take strings from a language spec that said, for instance, that they could be mutable. They have to force that on the JVM by having my own type and conversions to and from. So because I am an immutability oriented language, I am very happy with Java's definition of a string being an immutable thing. So Clojure strings are Java strings.

[Audience member: Question.]

Yes.

[Audience member: Is there any way to reference underlying units. In other words, to say that tbd centimeters or meters, or something like that. You do not know.]

No. Try Frink. Have you ever seen it?

[Audience member: No.]

Oh. You will love it. You can add all kinds of units and figure out how many balloons of hydrogen it would take to move a camel across this much distance. It is amazing. Units for absolutely everything. Old ancient Egyptian units. It is fantastic. The guy is just a fanatic about precision, making sure you do not lose anything. But you can arbitrarily multiply all kinds of units. Everything is preserved. Everything works correctly. Fantastic framework.

[Time 0:26:07]

[Audience member: What was the name?]

Frink. F R I N K.

[Frink https://frinklang.org/ ]

[Audience member: And is that Java, or is that Lisp?]

Frink is a language for the JVM. It is its own language. But it is a lot of fun. I have seen the guy talk, and he has some great examples. Some involve how many belches it would take to move a hot air balloon to the moon, and things like that.

OK. So we have string literals in double quotes. We have characters

are preceded by a slash, a backslash. So that is a character literal.

And that is a big C Character, Java character.

Now we are going to get to two things that are possibly a little bit

different, because they are not first class things in Java. One would

be symbols, which are identifiers. They cannot contain any spaces.

They have no adornments. Symbols are used as identifiers, primarily

in code, but they can be used for other things as well. They are

first class objects like strings. If you have one of these things,

you can look at it, and it will be a symbol, clojure.lang.Symbol.

[Audience member: Are fred and ethel two symbols?]

fred and ethel are two symbols. That is correct.

The other thing Clojure has are keywords, which are very similar to

symbols, except they always designate themselves. So they are not

subject to evaluation, or mapping to values by the compiler like

symbols are. So a symbol might be something you would use for a

variable. You could make fred be equivalent to 5. You could never

make :fred be equal to 5. :fred will always mean itself.

So when it gets evaluated, the value of the keyword :fred is the

keyword :fred. It is sort of an identity thing. And they are

extremely useful.

[Time 0:27:59]

They are very useful, in particular, as keys in maps, because they are very fast for comparison, and they print as themselves, and read as themselves. That will make a little bit more sense in a minute.

There are Booleans. This is different from Lisp, although there is

still nil as false. But in addition, there are proper true and

false, mostly for the purposes of interoperability. It ends up that

you cannot solve the nil becoming false problem. At least, I could

not. So there are true and false, and they are for use in

interoperability with Java. You can use them in your Clojure programs

as well, but conditional evaluation in Clojure looks for two things:

it looks for false or nil, which is the next thing I am going to

talk about.

nil means "nothing". It also is the same thing in Clojure as Java

null. It did not have to be, but it is. So you can rely on that.

So nil means nothing, and it is the same value as Java null. So

when you get back nulls from Java, they are going to say nil. nil

is a traditional Lisp word.

But I like it, because also traditionally in Lisp, you can say if nil, and it will evaluate to the else branch, because nil is false.

nil is not true. So that is another literal thing, that nil.

There are some other things. There are regex literals. So if the reader reads that, it is just a string regex, with exactly the same syntax as Java's, preceded by a hash, will turn into a compiled pattern. So at read time, you can get compiled patterns, which you can then incorporate in macros, and things like that, which is very powerful. And shows how that delineation between compilation and run time is a little bit fungible.

[Time 0:30:04]

[Audience member: So nil is different from the empty list.]

Correct. And there is a good reason for that. And the reason is:

empty list is no longer as special as it was, once you have empty

vector and empty map. However the sequencing primitives, the

functions that manipulate sequences, return nil when they are done,

not the empty list. So that aspect of being able to test for the end

of iteration with if is still there.

So Clojure sits in a unique point. He is asking about aspects of

Clojure that differ a little bit from Common Lisp and Scheme. There

is a long standing fight between what should the difference between

false, nil, and the empty list be? Should they be unified? They are

in Common Lisp. Should there be some differences? There are some

differences in Scheme. Clojure actually does some of both. There is

false. However, nil is still testable in a conditional. It does

not unify nil and the empty list, which is a difference from Common

Lisp.

However, all of the sequencing or list operations, when they are done,

return nil, not the empty list, which is an important thing for

Common Lisp like idioms, where you want to keep going until it says

false, as opposed to having to test for empty explicitly, which we

would have to do in Scheme. Does anybody know Scheme here? Yeah, you

know Scheme, but you know both, so you know what I am talking about.

For everyone else, I would not worry too much about that, because you

would not have presumed nil would have been the empty list. Right?

Probably not.

[Time 0:31:44]

slide title: Data Structures

+ Lists - singly linked, grow at front

+ (1 2 3 4 5), (fred ethel lucy), (list 1 2 3)

+ Vectors - indexed access, grow at end

+ [1 2 3 4 5], [fred ethel lucy]

+ Maps - key/value associations

+ {:a 1, :b 2, :c 3}, {1 "ethel" 2 "fred"}

+ Sets #{fred ethel lucy}

+ Everything Nests

OK. So those are the atomic things. They cannot be divided. That is what atomic means. A number is not a composite thing. But there are composite or aggregate data structures in Clojure, and they are kind of the core abstractions of computer science.

[Time 0:32:06]

One is the list. And in this case, I mean very specifically the singly-linked list. And even more specifically the singly-linked list in which things get added at the front. So when you add to a list, you are adding at the front. The list is a chain of things, which means that finding the N-th element is a linear time cost. It is going to take N steps to do that.

On the other hand, taking stuff on and off the front is constant time, because that is the nature of a singly-linked list. So it has all of the performance promises of a singly-linked list with stuff at the front.

And its literal representation is stuff inside parentheses, separated by spaces. There is no need for commas. You will see some commas. Commas are white space in Clojure. They are completely ignored. You can put them in if it makes you feel better, or makes things somewhat more readable, but they are not actually syntax. They are not considered by the evaluator.

So any questions about lists? Stuff in parens.

[Audience member: tbd]

Right. Well these commas, the ones between (1 2 3 4 5) and (fred ethel lucy), are actually English commas. But there are some commas,

for instance when we get down to maps here, you see commas inside the

data structure? Those are ignored. Those are white space.

[Audience member: I understand white space in lists. What about the difference between comma and decimal in a number?]

[Time 0:34:00]

I do not support any commas inside numbers. The printed representations of numbers in Clojure are those of Java.

[Audience member: tbd]

In Lisp?

[Audience member: tbd]

No. In Lisp they grow at the front. Cons a onto something makes

a the first thing in that list. And that is true of Clojure, too.

[Audience member: Is it based upon java.util.List?]

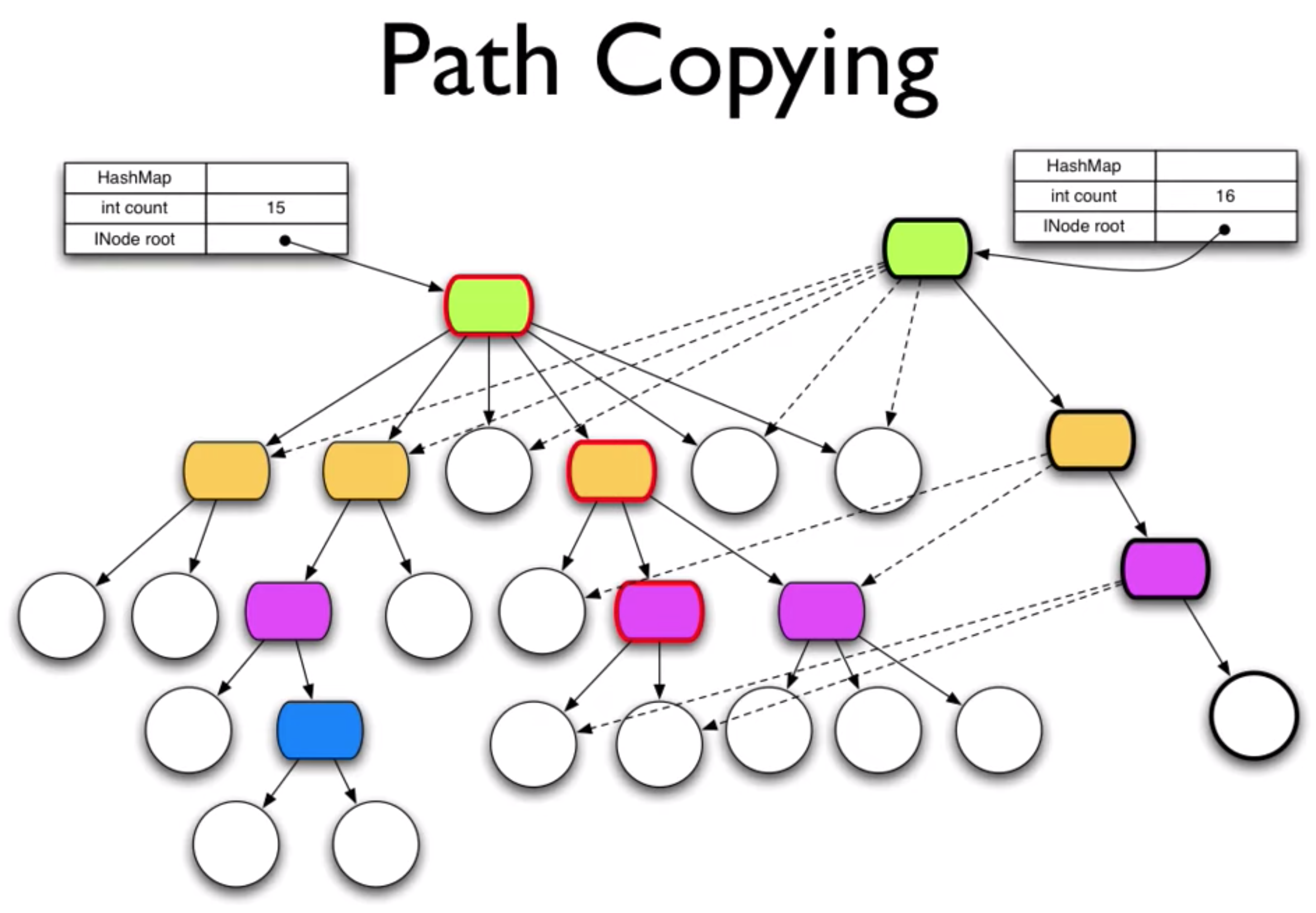

Absolutely not. All of these data structures are unique to Clojure. I am only giving you some very high level descriptions of their representation and their performance characteristics, but what we are going to find out later is: all of these things, and in particular I am talking about adding to the lists, all of these data structures are immutable. And they are persistent, which is another characteristic I will explain a little bit later.

So these are very different beasts, and they have excellent performance. Yet they are immutable, and it is sort of the secret sauce of Clojure. Without these, you cannot do what I do in the language.

[Audience member: In the second list, fred ethel lucy tbd]

That is correct.

[Audience member: What fred references, though, can it change?]

Again. How this gets interpreted, we are going to talk about it in a little bit. Right now what you are looking at is a list of three symbols. You may end up with, in your program, a data structure that is a list of three symbols. You may pass this to the evaluator and say: evaluate this, in which case it is going to try to evaluate each of those symbols and find out its value, and treat the first one as if it was a function. But we are not there yet.

[Time 0:35:57]

So that is a list of three symbols. The list at the end is a list of one symbol and three numbers. So heterogeneous collection are supported in all cases. I did not necessarily show them everywhere, but they are. It is not a list of something. It is a list. It can contain anything, and any mix of things.

OK with lists?

The next thing is a vector. It uses square brackets. That should imply, I would hope, for Java programmers and people from that domain, array. Square brackets mean arrays. Well, they do now.

So a vector is like an array. In particular, it supports efficient indexed access. It is an expectation you would have of a vector you would not have of a linked list, that getting at the 50th guy is fast. It is not going to be 50 steps to do that. And the Clojure vectors meet that performance expectation. Fast indexing.

In addition, it is a little bit like java.util.Vector, or

ArrayList, in that it supports growing, and in this case, at the

end. And that also is efficient, as efficient as your expectation

would be of ArrayList. That is a constant time operation to put

things at the end.

Similarly, it can hold anything. The first is a vector of five numbers, the second is a vector of three symbols.

[Audience member: Must it be homogeneous?]

No. All of the collections can be heterogeneous.

OK so far? So that is going to behave like an array, in terms of being able to find the N-th element quickly.

And finally, as a core data structure we have maps. And a map is like a Java map, or any kind of associative data structure, in providing a relationship between a key and a value, each key occurring only once, and having a mapping to a value.

[Time 0:38:08]

So the way they are represented is in curly braces. And they are represented simply as key, value, key, value, key, value. Again, the commas do not matter. So they are white space. They get eliminated. For instance, in the second map you see there, that is a map of the number 1 to the string "ethel", and the number 2 to the string "fred". You do not need the commas.

And the expectation with a map is that it provide fast access to the value at a particular key. There are usually two kinds of maps you would encounter in ordinary programming languages. One would be sorted. Some sort of sorted map, in which case the access is going to be typically log N to find a particular guy, depending on how many things are in the map, because they use trees, or red black trees, and things like that. And Clojure does have sorted maps.

The one you get from the literal representation like this is a hash map, and the expectation of a hash map is constant, or near constant, time lookup of values at keys. And that maps to hash tables.

So what you have in the Clojure literal maps is the equivalent of a hash table. It is fast.

Everybody OK so far?

[Audience member: What would happen if I introduce another key in this?]

Another :a? It will be replaced.

[Audience member: So the last number replaces the first one.]

Correct. There is only one instance of a key in a map. Is that your question?

[Audience member: Yeah.]

Yes. So if you were to say ...

[Audience member: No, I am saying if I type it out like this, and

after the :c 3 put :a again, is that an error, or is it just a

replacement?]

[Time 0:40:02]

It is probably a replacement. I see, in the same thing, yes. I do not think it is an error. That is a good question. I might type it in later for you.

[Audience member: tbd]

Yeah.

[Audience member: tbd set]

It is the same thing. Well, there is no associated value, so fred

will be there.

So let us talk about sets. The fourth thing I am showing you here is sets. Sets are a set of unique values. Each value occurs only once in the set. And really the only thing a set can do for you is tell you whether or not something is in it. There is no associated value. It is just: does the set contain this key?

Do you have a question?

[Audience member: Yes. tbd does it keep it in a sorted order?]

There are sorted sets and hash sets, same thing as with the maps. The sets here are hash sets. So no, the order is not retained. You can request a sorted set, and the order will be the sort order.

Does that answer your question? OK.

[Audience member: What is the test for equality?]

What is the test for equality?

[Audience member: Yes, for sets.]

Equal. The equal sign = is the test for equality, and equality

means the same thing for everything in Clojure. It means equal value.

You will see that Clojure definitely deemphasizes identity, completely in fact. There is an identity function, and I have yet to use it. Clojure is about values. Identical contents are identical by equals.

That is made faster than you might imagine by caching hash values. But equality is equality of value in Clojure.

[Time 0:42:00]

[TBD: Is it? I don't think Clojure = uses hash values at all?]

[Audience member: And there is no mutability tbd]

Immutability helps, certainly. Well if you have ever read Henry Baker's paper on Egal, Clojure implements Egal, finally. If you have not, then do not worry about it.

[This article gets into great detail about what equality means in

Clojure, including some brief descriptions of small differences

between Clojure = and Henry Baker's Egal:

https://clojure.org/guides/equality

TBD: Rich says above that equality comparisons on collections are made

faster by caching hash values. I know that it is made faster in most

cases by quickly returning true if the two collections (or

sub-collections) being compared are identical objects by a very fast

pointer equality check, i.e. Java == on object references, but I do

not think anything in the implementation of equality uses cached hash

values. Lookups of collections inside of hash maps and hash sets is

sped up by caching hash values.]

So yes, equality is equality of value. All right? Yes.

[Audience member: tbd]

No. You can make arrays, and you can interact with Java arrays that

are arrays of either objects or native arrays. You can say

float-array and a size, and you will get an array of floats. So you

have the ability to do Java stuff.

I am going to emphasize the Clojure data structures, because they let you do what Clojure lets you do. You can access Java, but as you start accessing mutable things, some of the things that Clojure can do for you, we cannot do. It does not mean that you are not allowed to do them.

But there is no point in me showing you how to interact with a Java array, except to show you the syntax, which I might later.

So the last part about this is that everything nests. A key in a map can be another map. It can be a vector. Anything can be a key or a value. Because of this equality semantics, there is no problem having a vector or a map whose keys are vectors. That is perfectly fine. So if you needed to use tuples as keys, you know pairs of things as keys, that is just completely doable.

[Audience member: Question in terms of tbd]

Well you can get the hash of a vector.

[Audience member: I mean as a programmer test, to invoke it, but rather the implementation of it. At an implementation level you can have a very complex structure as the key, that sounds expensive to me.]

[Time 0:44:03]

Well it depends on what you are doing. I would imagine that really complex structures are not frequently used as keys, but they could be. Can that be helped? Yes, the fact that these are hashed by default means that once, and once only, the hash value of some aggregate structure will be calculated. And that will be cached, so there is a quick hash test, otherwise we do the deep value check.

But, again, I do not think you are going to encounter complex data structures as hash values that often. But using kind of small things like tuples or other small maps as keys is tremendously useful. It is really really handy to not even have to think about that.

I think we have got one other Clojure programmer arrived, who can possibly attest independent of me how Clojure's performance is. How is Clojure's performance?

[Audience member: Fine for me.]

[Editor note: I recognize the voice as that of Stuart Sierra, who has written many articles and widely used libraries for Clojure.]

Yeah.

[Audience member: tbd]

Right. Well now there is some extra numeric goodness in there. But these data structures are pretty good.

What is the reality? The reality of these data structures is: I have tried to keep them all within one to four times of Java data structure -- the equivalent Java data structure. In other words, hash map, vector, well singly linked lists are pretty straightforward. So they are within striking distance.

The B side is: in a concurrent program, there is no locking necessary for use with these data structures. If you want to make an incremental change to a data structure in a certain context, there is no copying required to do that. So some of these other costs that would be very high with a mutable data structure vanish. So you have to be very careful in looking at that.

[Time 0:45:55]

The other thing that is astounding to me, at least, is that the lookup

time -- again the add times are higher than HashMap, but the lookup

times can be much better, because this has better cache locality than

a big array for a hash table.

OK. We are all good on this? I probably have to move a little bit quicker. Yes. More quickly.

[Audience member: tbd]

There is destructuring, yes. I actually will not get to talk about that today, but there is destructuring. There is not pattern matching. But there is destructuring to arbitrary depth of all of these.

Destructuring means a way to easily say: I want to make this set of symbols that I express in a similar data structure map to corresponding parts of a complex data structure I am passed. So Clojure has that. It has some really neat destructuring capabilities.

[Time 0:46:54]

slide title: Syntax

+ You've just seen it

+ Data structures _are_ the code

+ Homoiconicity

+ No more text-based syntax

+ Actually, syntax is in the interpretation of data structures

All right. So what is the syntax of Clojure? We just did it. I am not going to talk about semicolons, curly braces, when you have to say this, when you have to have a new line, or anything else. Because the structure of a Clojure program is a data structure, or a series of data structures. There is no other stuff. There are no rules about where things go. There are no precedence rules. There is nothing else. You write a Clojure program by writing the data structures I just showed you. That is it.

[Audience member: Which means, how does one write an if or loop?]

I will show you.

So you write a program by writing data structures. The data structures are the code. That has huge implications. It is the nature of Lisp. There is a fancy name for it called "homoiconicity", and it means that the representation of a program is done in the core data structures of the program.

[Time 0:48:04]

Which means that programs are amenable to processing by other programs, because they are data structures. So I am not going to talk any more about text based syntax, because there is no more.

Now many people claim of Lisps: well Lisp has no syntax. And that is not really true. It does not have all of this little fiddly character syntax, necessarily. There is syntax to the interpretation of the data structures. We are going to see a lot of lists. They have different things at the front. The thing at the front will tell you the meaning of the rest.

[Time 0:48:46]

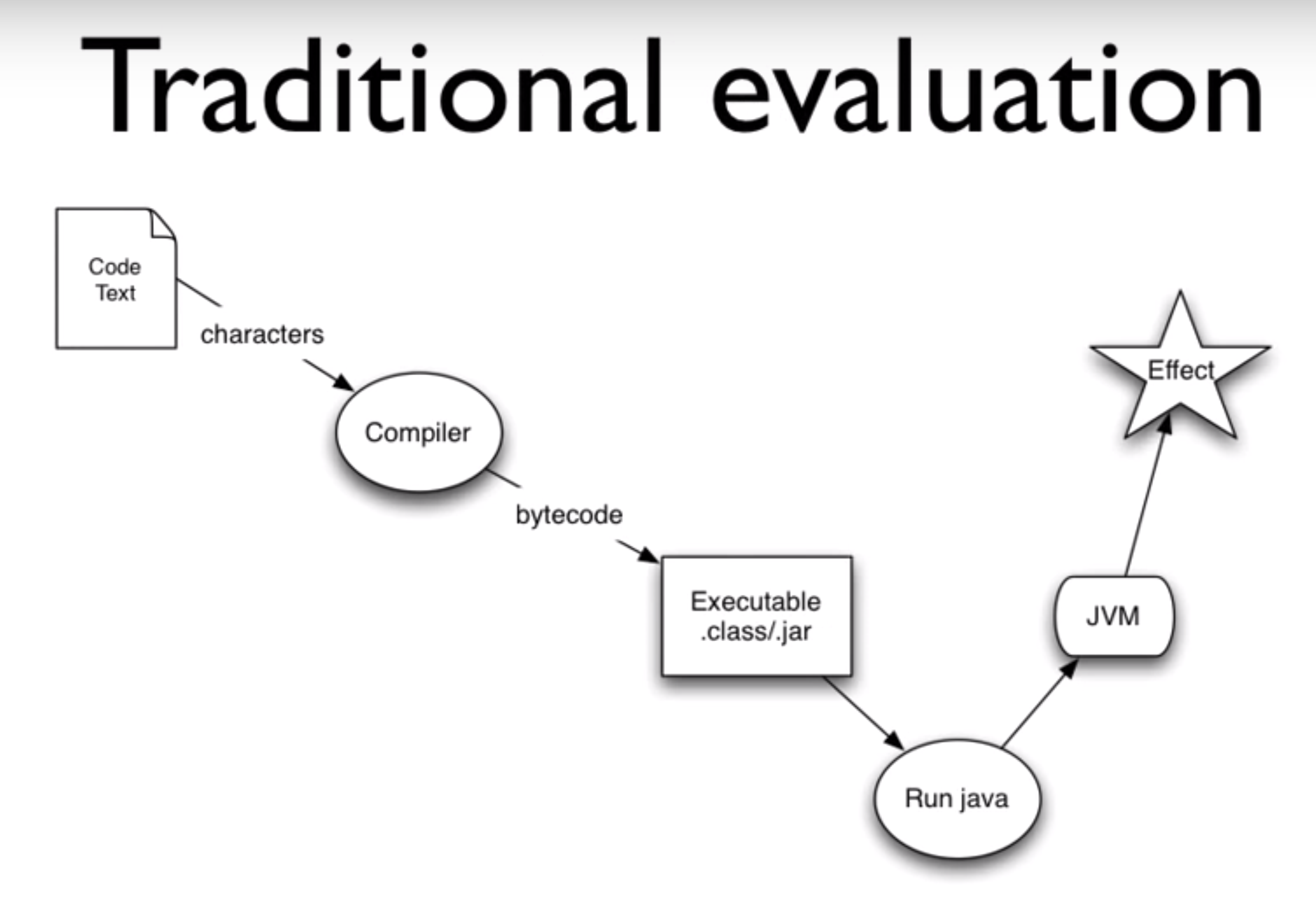

slide title: Traditional evaluation

So let us talk a little bit about evaluation. So how does this all

work? This we should all know from Java or many other languages like

Java. We type our program into a text file, and we save it. And then

we send those characters, that text, to the compiler, who has a very

involved abstract syntax tree, and parser, and lexer, that interpret

the rules of the language. This is what constitutes a character.

This is what constitutes a number. And then furthermore, if you have

said if and you have put parens, then you said some stuff and you

put a semicolon, and you happened to have put else and you are still

in this construct called if.

Things like that. It knows all about that, and it deals with the text. And it will tell you if you have met the requirements in terms of it being a valid program. And it will turn it into something that can run. In the case of Java, that something will be byte code. And it will go into a class file or a JAR file. We know this.

And then, there is a separate step, which is called running. And we

take that stored executable representation and we ask it to happen,

usually, in this case, we will say java dash something class file,

and it will run.

[Time 0:50:01]

And it will run, and then it will end, and it will be over. And we can try again if we did not like it. That is the traditional edit, compile, run, be disappointed, start over.

[Audience member: tbd]

Oh, correct. But I am talking about the development process. Yeah, so the run time is just that part.

[Audience member: Hopefully in your code tbd]

Until you realize it is not working, and you have to ask everybody to please wait for our downage while we fix it.

[Time 0:50:41]

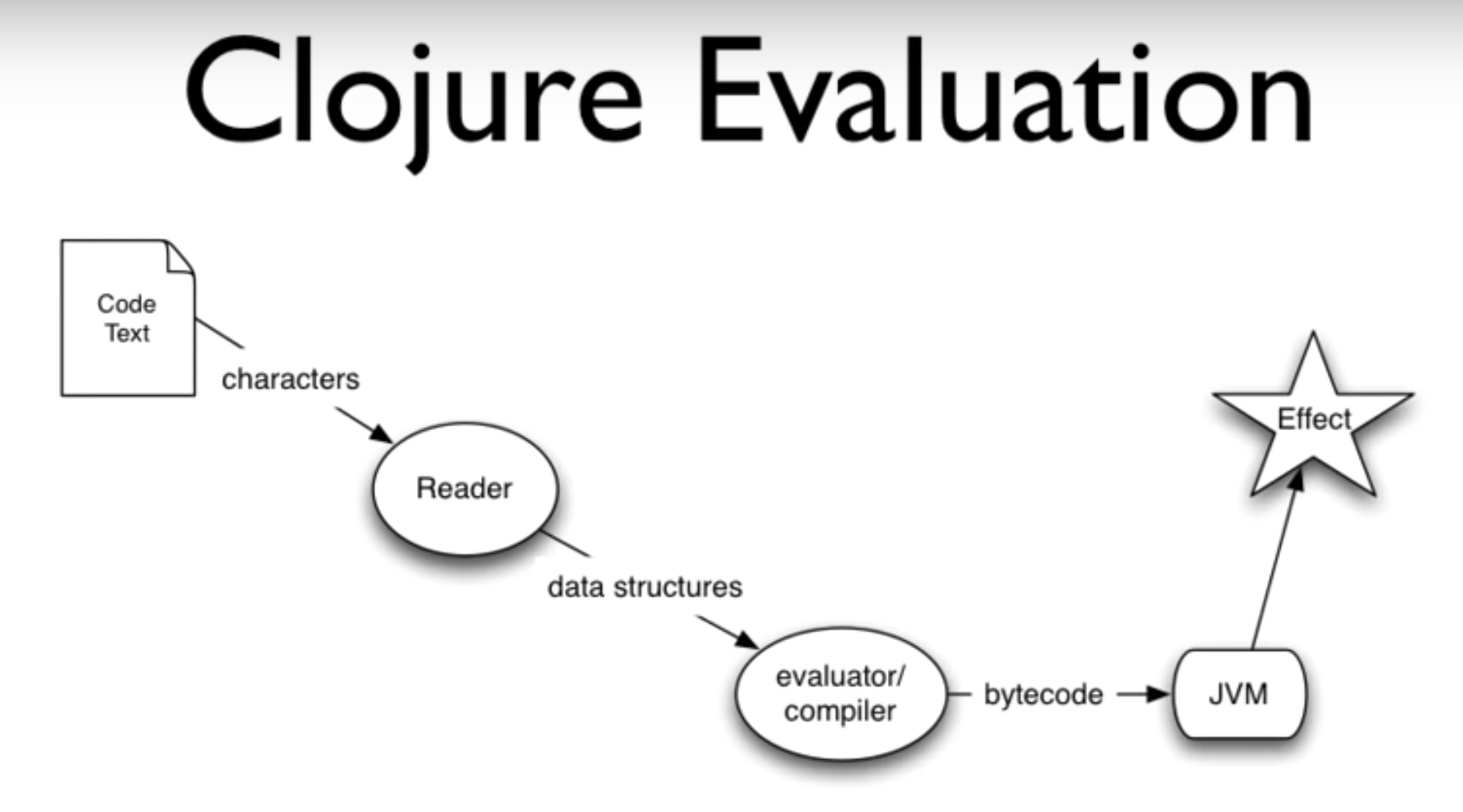

slide title: Clojure Evaluation

Right. That is the difference. If you read about Erlang, which is getting a lot of press, they will tell you about phone switches, and how that is really not allowed. And Lisp was doing this for a very long time, this kind of live hot swapping of code in running systems.

I think it goes more, in this case it is less about the production thing, than it is about what is the nature of developing your program? Because as a developer, seeing it run and saying: Oooh! That was bad. I wonder what happened? I wish I had run it in debug mode. I wish I had put a breakpoint somewhere interesting, and I am really sad that I spent an hour calculating that data, and dropped it on the floor, because I have to do it again with a breakpoint in.

That is a lot different experience than keeping your program around, and having that data stay loaded, and fixing your function and running it again, without starting over.

So that is what happens in Clojure. You take the code. Text, could be. There is character representation, and what I showed you there can be represented in characters, in ASCII.

It does not go first to the evaluator. It goes to something called the reader. And this is a core part of what makes something a Lisp, which is that the reader has a very simple job.

[Time 0:52:00]

Its job is to take the description I just told you: a keyword starts with a colon, and a list is in parentheses, and a map is in curly braces and it is pairs of stuff. Its job is to take those characters and turn it into data structures, the data structures I described.

You start with a paren, you say stuff, you close the paren, that is going to become a list when the reader is done with it. If it starts with square brackets, that is going to become a vector when the reader is done with it.

So what comes out of the reader are data structures. And what is unique about a Lisp and Clojure is that the compiler compiles data structures. It does not compile text. It never sees text. What the compiler gets handed is, maybe, a list with three symbols in it. Or a vector with 5 numbers in it. That is actually what the compiler has. It has the data structure in hand, with actual data in it. Not text.

And it compiles it. And in the case of Clojure, it is a compiler.

There are many -- well there are not actually many Lisps that are

interpreters. Many people believe that Lisp is interpreted, and it is

certainly easy to make an interpreter for Lisp that would take those

data structures and, on the fly, produce the values they imply. But

Clojure is a compiler, and in particular Clojure compiles those data

structures to Java byte code, right away. There is no interpretation

in Clojure. So it is a compiler. It produces byte code just like

javac does.

And because it is an interactive environment, it presents that byte code right away to the JVM to execute. And it executes right away, and you can see the effect.

[Audience member: Are they living in the same VM as the application is running?]

When you are in the REPL, you have a VM. Right. You have one thing. So yes, your environment is your program. Your compiler is in your program.

[Time 0:54:02]

[Audience member: tbd]

Yeah. I mean some commercial Lisps give you tools to take out the compiler in production, mostly because they do not want you giving away their compiler. Normally there is no reason to prevent that, because it is a useful thing to have, particularly when you want to load code later to fix problems. You are going to need that compiler there. So in Clojure there is no strip out the compiler option.

[Audience member: tbd]

We will see that there is a core of Clojure. The data structures are written in Java. The special operators are written in Java. And then most of the rest of Clojure is written in Clojure.

[Audience member: Right. But OK, so no native code.]

There is no native code. Clojure is completely a pure Java project. There is no native code. There are no C libraries. Nothing. It is all Java, either generated by Java itself, or generated by Clojure. It does not turn off the verifier, or anything like that, in order to get performance. There have been some Schemes that have tried to do that. Clojure is completely legit that way.

So when we have this separation of concerns between the reader and the evaluator, we get a couple of things.

[Time 0:55:22]

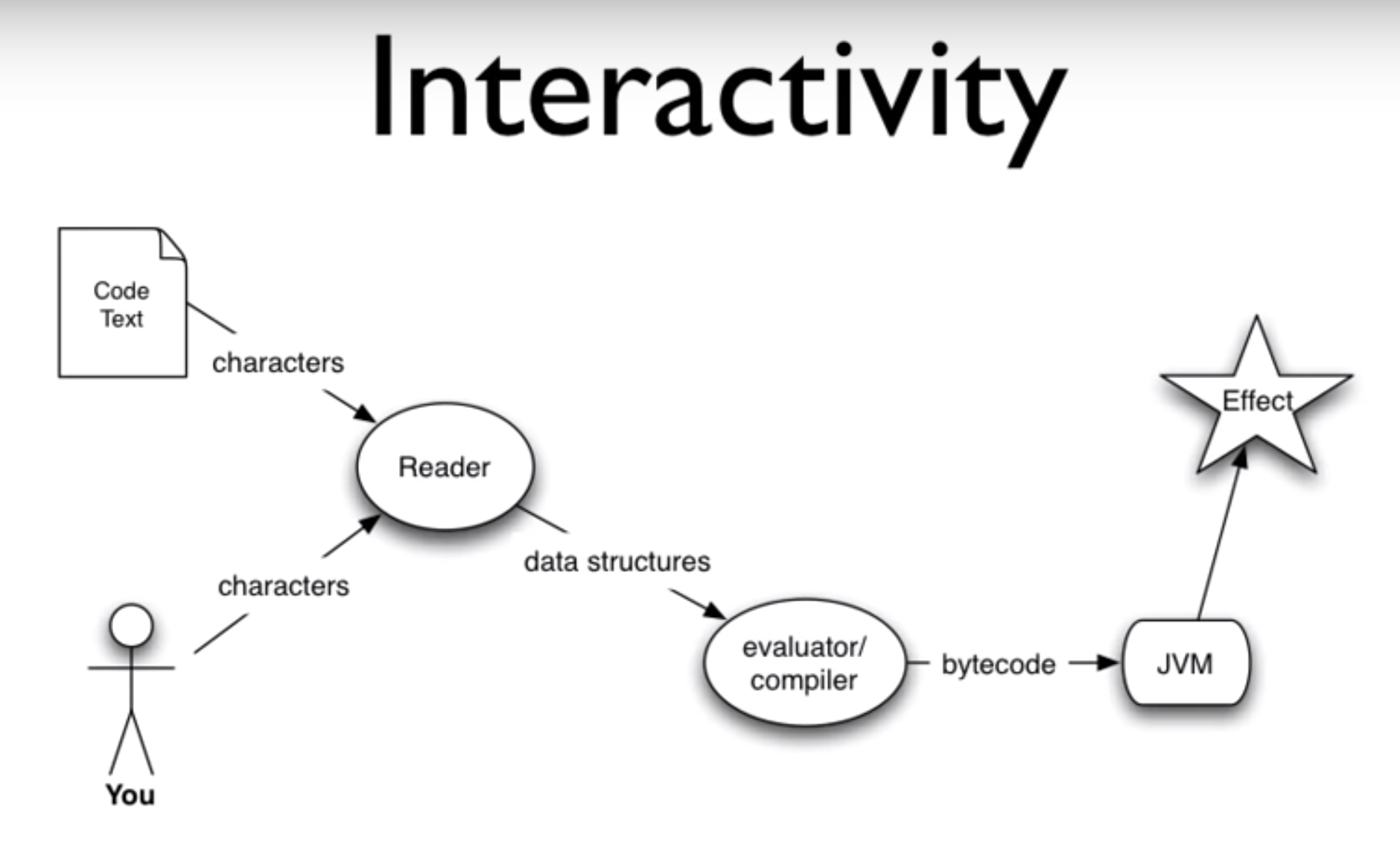

slide title: Interactivity

One of the things we get is: we do not have to get the text from a file, right? We can get it right from you. You just saw me type right into the REPL, an expression. It never went through a file. It never got stored. So the first thing you get is this kind of interactivity. You can just type in stuff and say: go.

That is a big deal. If you have been programming in Java or C++ long enough to remember when the debuggers did not give you the ability to evaluate expressions at a breakpoint, you remember how hard that was. You always have that capability here, to have expressions directly evaluated.

What else do we get from this?

[Time 0:56:01]

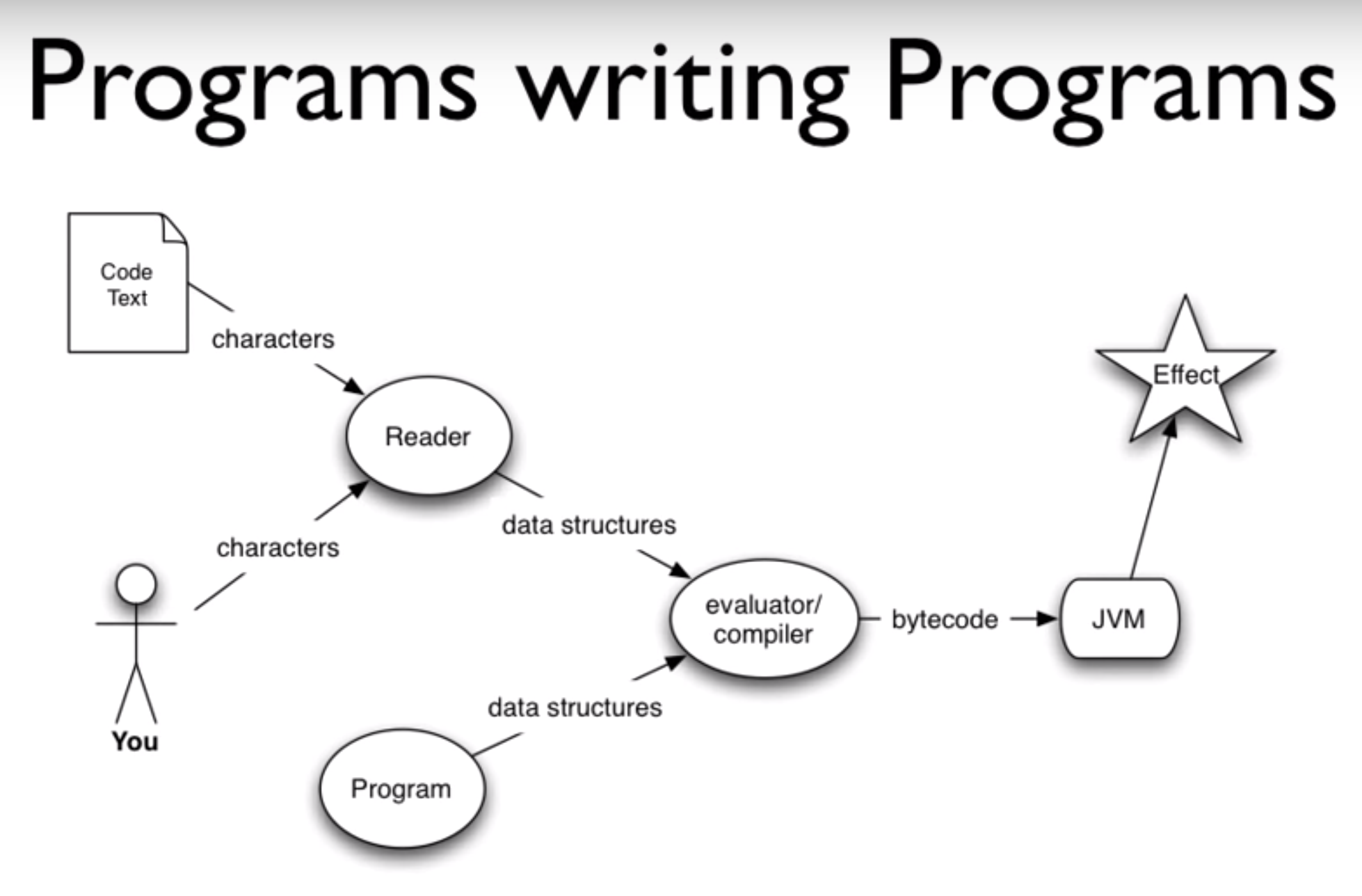

slide title: Programs writing Programs

Well we get the ability to skip the characters completely. For instance, it is quite possible to write a program that generates the data structures that the compiler wants to see, and have it send them to the compiler to be evaluated.

So program-generating programs are a common thing in this kind of an environment. Whereas this kind of stuff, when you are doing it with text, is really messy.

[Audience member: By the way, one observation just struck me tbd give me a good way to be able to say it. There are firms I know, that because of the compliance requirements that they have, they might be very comfortable with code tbd into a reader for tbd. But is there an option of saying it is always live, this person in a production environment to influence the code that is being executed. That is a scary thought.]

Well that is a security policy thing, whether or not you expose this in a production system. So I am talking about: you could if you needed to, you could have that over a secure socket channel, and have it be just an administrator who knows what they are doing have that capability. Because the alternative is downing your system, if you do not have that.

And of course opening this in a production system, that is completely a policy thing. It has nothing to do with the language. Except if your language does not let you do it, you cannot do it.

[Audience member: That is fair.]

So it does. The other thing is that these data structures, you might write this program and have this happen directly. Then you might say: I like this program. Let me take those data structures, and there is a thing called a printer, which will turn them back into that, which you could store, and somebody could sign off on, and say: this is the canonic program, which are program-generated, that we are going to use. And we will lock that down, and do whatever.

Yes.

[Audience member: So in the data structures physical files, or ...]

No. They are in-memory data structures.

[Time 0:58:00]

The ones your program would see. So an instance of

clojure.lang.PersistentVector might get handed to the compiler. The

compiler has got to deal with it, figure it out.

So there is one more thing that this allows, and this is the secret sauce of all Lisps, ...

[Time 0:58:23]

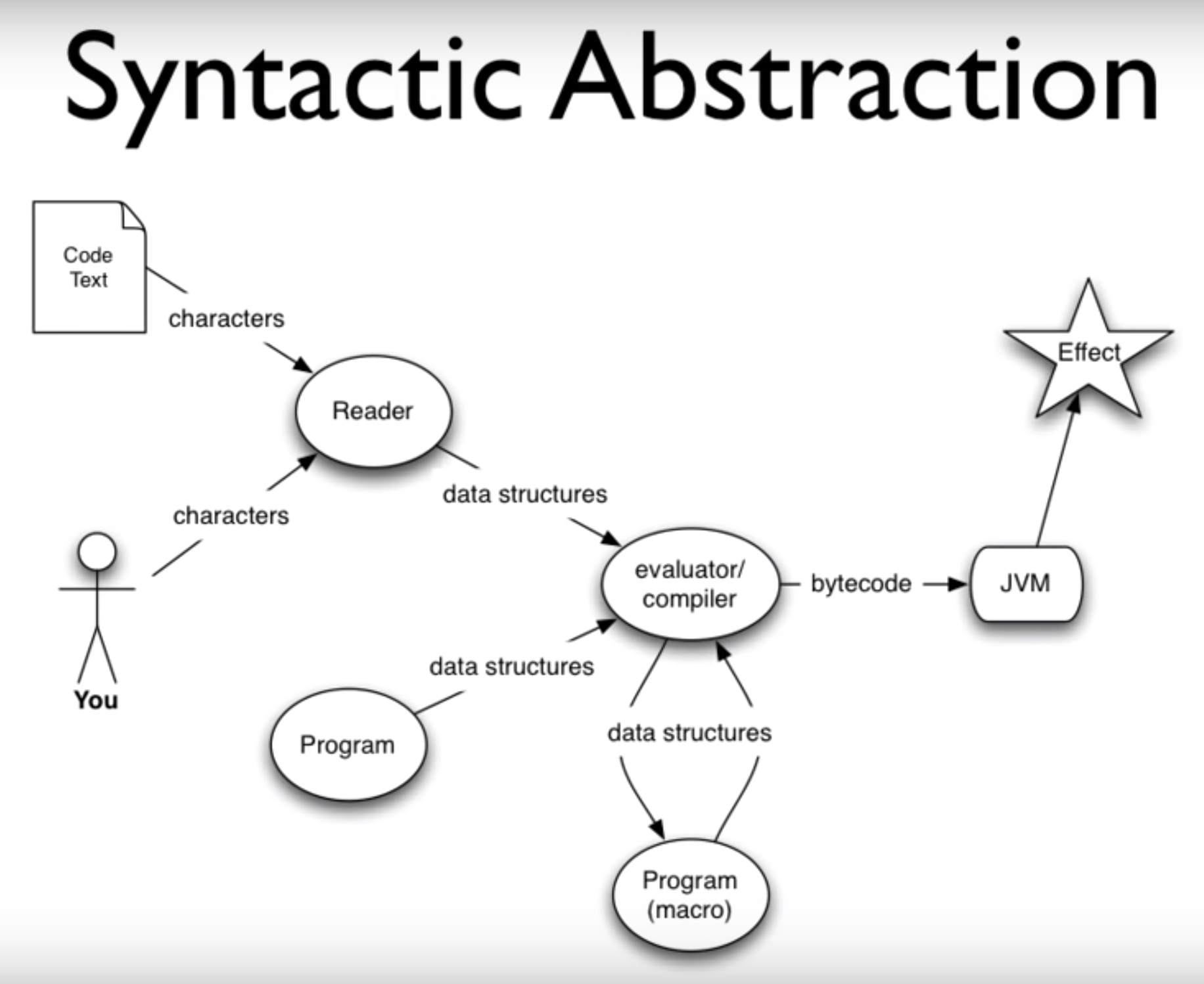

slide title: Syntactic Abstraction

... including Clojure, which is: what would happen ... I mean, it is fine to sit standalone and write a program that generates a program.

But what would happen if we said: you know what? We are handing these data structures to the compiler. It would be great if the compiler would let us participate in this. If it could send us the data structures, and we could write our own program, a very small program, and give it back different data structures, then we could participate, very easily, in the extension of our language.

Because this compiler, it is going to know how to do what it knows how

to do. It is going to know what to do with a vector. It is going to

know what if means, and a couple of other things. But there will be

new things that we will think of, that we would love to be able to

say.

When you have something that you would love to be able to say in Java, what do you have to do?

[Audience member: tbd]

You have to beg Sun, and wait for years, and hope other people beg for the same things, and you get it. That is it. You have no say. You have no ability to shape the language.

In Lisp, that is completely not what it is about. It is about getting you in the loop. And in fact, the language itself has a well defined way for you to say: this is a little program I would like you to run. When you encounter this name, I do not want you to evaluate it right away. I would like you to send me that data structure. I know what to do with it. I am going to give you back a different data structure, and you evaluate that.

[Time 1:00:00]

That is called a macro. And it is what gives Lisps and Clojure syntactic abstraction and syntactic extensibility.

[Audience member: Can that happen in the context of a namespace?]

Yes, it can. There are namespaces in Clojure, and they allow me to have my cool function, and you to have your cool function.

[Audience member: By the same name.]

Cool function, yes.

[Audience laughter]

So that is what makes Lisp amazing. It is something that I will not have time to dig deeply into tonight. If you can come away with at least the understanding that that is how it works, that is how it is possible, and the fact that these are data structures here and here makes it easy.

You can theoretically say: oh, I could write something if the compiler could hand me the abstract syntax tree, I could navigate it with some custom API and do whatever, it is not nearly the same, though, when what the compiler is handing you are those three data structures I just showed you that every program knows how to manipulate, and has a wildly huge library that directly can manipulate.

So that is how Lisp works.

[Time 1:01:09]

slide title: Expressions

+ Everything is an expression

+ All data literals represent themselves

+ _Except:_

+ Symbols

+ looks for binding to value, locally, then globally

+ Lists

+ An operation form

I am going to try to speed up a little bit.

In Clojure, unlike Java, everything is an expression. So you know in

Java there is a difference between declarations and statements and

expressions. There is no distinction in Clojure. Everything is an

expression. Everything has a value. Everything gets evaluated and

produces a value. Sometimes that value is nil, or not particularly

meaningful, but everything is an expression.

So the job of the compiler is to look at the data structures and evaluate them. There is a really simple rule for that. This is slightly oversimplified, but in general you can understand it this way.

All of those data literals I showed you: symbols, numbers, character literals, vectors, maps, sets, are all evaluated by the compiler to represent themselves,

[Time 1:02:04]

except lists and symbols. Lists and symbols by default are treated specially by the evaluator.

So when it reads a list of symbols, in particular, it is going to do some work. It is not just going to return the list of symbols to your program. It is going to try to understand them as an operation, which I will show you in a second.

So symbols, the compiler is going to try to map to values, like

variables. Like you know in a variable, you can say int i = 5.

Later in your program in Java you say i. Java is going to try to

figure out, oh, that is 5. That is the i you said up there.

Same thing in Clojure. When you use a symbol in your data structure,

Clojure is going to try to find a value that has been associated with

that symbol. It can be associated with it through a construct called

let, sort of the way you create a local name, or through def,

which is the way you create a global name.

Or it is a list, and it is going to say: this is an operation of some sort. I have to figure out what to do with a list.

[Time 1:03:14]

slide title: Operation forms

+ (op ...)

+ op can be either:

+ one of very few special ops

+ macro

+ expression which yields a function

So how does that work? Well, again, we said what is the data structure? It has parens. It starts with something. It may have more stuff, or not. But from the evaluator's standpoint, all that matters is the first thing. The first thing is the operator, or op. That is going to determine what to do. And it can be one of three things.

It can be a special op. This is magic. This is sort of -- this is the stuff that is built into the compiler, upon which everything else is bootstrapped. So some things are special. I am going to enumerate them in a second.

It can be a macro. Like we saw before, there is a way to register

with the compiler to say: when you see the op my-cool-thing,

[Time 1:04:00]

go over here and run this function, which is going to give you

something to use in place of the my-cool-thing call.

And the third thing it could be is an ordinary expression. It is going to use the normal means of evaluating an expression. And it is going to say: whatever value that yields, I am going to treat as a function and attempt to call with the calling mechanism of Clojure, which is not limited to functions, but its main purpose is for functions.

So for people who know Lisps, Clojure is a Lisp-1. It is a Lisp-1

that supports defmacro well, and the use of namespaces and the way

backquote works makes that possible, and everyone else can ignore

that.

[See this link for more background on Lisp-1 vs. Lisp-2: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Common_Lisp#The_function_namespace ]

[Audience member: Before you step away, that last bullet point, an expression which yields a function, as opposed to: it is the function.]

Well, what it is going to encounter is, it is going to encounter a

list, and the first thing is going to be the symbol fred. fred is

not a special operator. No fred in Clojure. Let us say no one has

registered a macro called fred. Then it is going to use the rules

we said before. What about symbols? To find the value of fred,

where hopefully someone before has said: fred is this function.

[Audience member: Or something that yields a function.]

It will keep evaluating. It is going to evaluate that expression, but there are other function-like things, or callable things in Clojure, in addition to functions. I will show you that in a second.

[Time 1:05:35]

slide title: Special ops

+ Can have non-normal evaluation of arguments

+ (def name value-expr)

+ establishes a global variable

+ (if test-expr then-expr else-expr)

+ conditional, evaluates only one of then / else

+ fn let loop recur do new . throw try set! quote var

So let us dig down into each of these three pieces.

Yes.

[Audience member: What if it does not encounter any one of those three?]

You have an error at run time. It will say: that is not a function.

It is actually what will happen. It will say: this is not a function.

If you said fred is (def fred 1), so fred is the number 1, and

you tried to call fred, or use fred as an operator, it is going to

say: 1 is not a function.

[Time 1:06:00]

Probably with a not very illuminating stack trace.

So special operators. There are very few. I think one of the things that is really cool about Lisps, and is also cool about Clojure, is you can define most of them in terms of themselves. One of the great brilliant things that John McCarthy did when he invented Lisp was figure out that with only, I think, 7 primitives, you could define the evaluator for those 7 primitives, and everything you could build on them. The core of computation.

It still gives me goose bumps when I say that. It is a beautiful thing. It really is. And if you have never looked at the lambda calculus or a Lisp from that perspective, it is quite stunning. His early papers are just great. They are just brilliant in a transparent way.

So let us look at a couple. I mean, I will show you two, and then I am going to list the rest.

def would be one. How do we establish a value for a name? There is

this special operator called def. It takes a name. Now that name

is going to be a symbol. Obviously, that cannot be evaluated, right?

Because the whole purpose of this special operator is to give it a

value. If the compiler were to use normal evaluation for the name

position, you would have a problem, because you are trying to define

what it means. How could you do that?

So one of the things about special operators that you have to

remember, and it is true of macros as well, is: they can have

non-normal evaluation of their arguments. Like, the arguments might

not be evaluated. In fact, def does not evaluate the name. It uses

is as a symbol. And it associates that symbol with the value. It

does not evaluate the symbol.

[Time 1:07:56]

So there is a simple way to say: if I say def name some expression,

the expression will be evaluated, the name will be mapped to that

value, or bound to that value. When you later go and say name, you

will get the value that was used to initialize it.

[Audience member: You can only do that once.]

You actually can do that more than once. You should not do that more

than once, unless you are trying to fix something. In other words,

def should not be used as set!. But you can use def to define a

function, and later you can use it again to fix it.

So the things that are defined by def are immutable at the root, and

it is the only escape hatch for that dynamic change in Clojure, that

is not governed by transactions or some other mechanism.

OK, so it establishes a global variable. Again, there are namespaces, but I do not have enough time to talk about them. It is all subject to a namespace. If you are in a namespace, and you define the name, then it is in your namespace, as distinct from that same name in another namespace. Namespaces are not the same as packages in Common Lisp.

They are very much different. In particular, symbols are not inherently in a namespace. Symbols have no value cell. They are not places. They are just labels. And there are Vars, which are the places, more like Common Lisp symbols.

if is another thing that is built in. And if you think about if

in your language, which you may not have ever done -- if you thought

about if as: why couldn't if be a function? Why can't I say if,

some test expression, some then expression, some else expression. Why

can't if be a function? I mean, it looks like a function. Well, it

does not actually look like a function in Java, but why can't it be a

function?

[Audience member: tbd]

It should only evaluate one of these two. That is why, right? And a function evaluates what? All of its arguments.

[Time 1:10:00]

So if you try to write if as a function, you would have a problem

because functions evaluate all of their arguments. So if has to be

special, and if is special in Clojure, too. It evaluates the test

expression, and then, depending on the truth or falsity of this, in

kind of a generic sense -- for Clojure, if this is nil or false, it

will evaluate that [the else expression]. If it is anything else, it

will evaluate this [the then expression]. But it will only evaluate

one of those two things.

[Audience member: It must have an else clause?]

No, it does not have to. The else can be missing, in which case it

defaults to nil.

So if is another example of something that has to be special. It

cannot evaluate all of its arguments.

And then we have these others. And in fact, this is it. There is

something [fn] that defines a function.

Something [let] that establishes names in a local scope.

A pair of things [loop and recur] that allow you to do functional

looping, to create a loop in your program.

Something [do] that lets you create a block of statements, the last

of which will be the value.

Something [new] that allocates a new Java thing.

Access to members of Java things [.].

throw and try do what you expect from Java. set! will rebind a

value. And quote and var are kind of special purpose for Lisp

manipulation things, so I am not going to get into them tonight.

Question.

[Audience member: Is that the entire list of things?]

Yes.

[Audience member: So then what is the equivalent of tbd.]

Of defmacro? defmacro is bootstrapped on this.

[Audience member: tbd]

No, there is defmacro. It is defined a couple of pages into the

boot script for Clojure, which I might show you, if we have some time.

Yes.

[Time 1:11:59]

[Audience member: tbd the reason for the exclamation point on the

set!, is it trying to say something to the programmer?]

Yeah, this is bad! What are you doing this for?

[Audience member: I thought that a macro would have to be a special operator tbd]

No. It ends up that in Clojure, macros are functions. And so there is just a way to, on a Var, say this function is a macro, and it will be treated as a macro, instead of as a function.

So that is a tiny set of things. In fact, when you take out the stuff related to Java, it is an extremely tiny set. I do not think I made it down to 7. One, two, three, four, five, six, seven, eight. I have more than McCarthy's set, but I do not have dozens.

So how could this possibly work? This is not enough to program with this.

[Time 1:12:56]

slide title: Macros

+ Supplied with Clojure, and defined by user

+ Argument forms are passed as data to the macro function, which

returns a new data structure as a replacement for the macro call

+ (or x y)

+ becomes: (let [or__158 x]

(if or__158 or__158 y))

+ Many things that are 'built-in' to other languages are just macros

in Clojure

[Audience member: tbd]

No. So we need macros. There are plenty supplied with Clojure. And what is beautiful about Clojure and Lisps is: you have the same power that I have to write macros. When you see the kinds of things that are implemented in Clojure as macros, you realize the kind of power you have as a developer, because you can write those same macros.

You could have written them. You do not have to wait for me. I am not Sun. This is not Java. You have something you want to express a certain way. You want to extend the language that way. If you can do it with a macro, you can do it without contacting me, or asking me for the favor of adding a feature for you, which means the language is much more extensible by programmers.

So let us talk a little bit about how they work. If we remember, we are getting data structures passed into the compiler. So it looked at the first thing.

[Time 1:13:58]

And somehow there is a way, and I cannot show you that tonight, to say: this name designates a macro. And associated with that name, then, is a function. The function expects to be passed the rest of the stuff that is in the parentheses.

So we had this cool function my-cool-macro. Maybe it expects to be

passed two things. The things it gets passed are not evaluated. It

gets passed the data structures that the compiler got passed, because

the compiler is going to say: you told me you knew how to do this.

Here are the data structures. Give me back the data structure I

should be processing.

So it is a transformation process where the macro is handed the data that is inside the parens as arguments to the function that the macro is. It will run any arbitrary program you want to convert that data structure into a different data structure. You can write macros that look stuff up in databases, that go and ask a rule based system for advice.

Most are not that complicated. But the thing is: it is an arbitrary program transformation. It is not a pattern language. It is not a set of rules about this can be turned into that. It is an arbitrary program, a macro. And in this way it is like a Common Lisp macro that, given the data structure, gives back its own replacement. Replace me, the expression that began with me, with this.

And then keep going, which may yield another macro, and another round of that, or it may yield something it already knows how to process.

[Audience member: So would it be correct to say that in Clojure, macros happen in run time context?]

No. This is happening at compile time. This is part of compilation. The compiler got handed this data structure. It said: ooh, it begins with a macro name, hands it to the macro. It comes back. That transformation occurs. It keeps compiling. Then you get byte code.

[Time 1:15:59]

After you get byte code, there is no more talking to the macro. So macros replace themselves with another data structure, and then compilation continues.

So we can look at a macro. You will notice on the list of primitives,

there is no or. or is not primitive in Clojure. And in fact, if

you think about or, or is not primitive. or is not a primitive

logical operation. You can build or on top of if.

The or I am talking about is like the double-bar or in Java in that,

what happens? If the first part tests true, what happens to the

second part? Not evaluated, right? It has still got that magic

thing. But if already knows how to do that. if already knows how

to do a conditional evaluation of only one of two choices, which means

we can define or in terms of if.

And so this is what happens. So or is a macro. When it is expanded

by the compiler, it returns something like this.

(let [or__158 x]

(if or__158 or__158 y))I am going to say (or x y). And this is what comes back. Another

data structure. It begins with let, which we have not seen so far,

but let says -- it takes a set of pairs, make this name [or__158

in the example] mean this [x in the example], inside the scope of

the let. It is like a local variable, except it is not variable.

You cannot vary it. But it has that same kind of scope.

So it says let us do that, and [tbd] these are why there are

parentheses, because this is going to be some expression. It looks

like x here, but it could be a call to calculate some incredibly

difficult thing that is going to take an hour, in which case I

probably would not want to repeat that more than once in my expansion,

because it would calculate that thing twice.

So we are going to take whatever that expression is, put it here,

assign this value to this variable name [or__158], which is made up.

Obviously you would not pick this name. It is a good machine-picked

name.

So it makes a variable and then it says if that thing is true -- we

took an hour to calculate this, right , we have the value -- if that

is true, return it.

[Time 1:18:03]

if [tbd] do not do this, if this is true. Otherwise it is going to

do y. And that is the implementation of or.

If the first thing is true, it returns it. Well in fact in Java you do not get a good value, but in Clojure you get the value that was true.

[Audience member: Then the invocation of any function can both return a value in a true form, or you interpret certain kinds of values ...]

All values can be placed in a conditional, not just Booleans, and it

is subject to the rules I said before: if it is nil or if it is

false, you will get the else expression evaluated. If it is anything

else, 7, the string "fred", anything else is true. So Clojure, like

most Lisps, allows any expression to be evaluated as the conditional

test here.

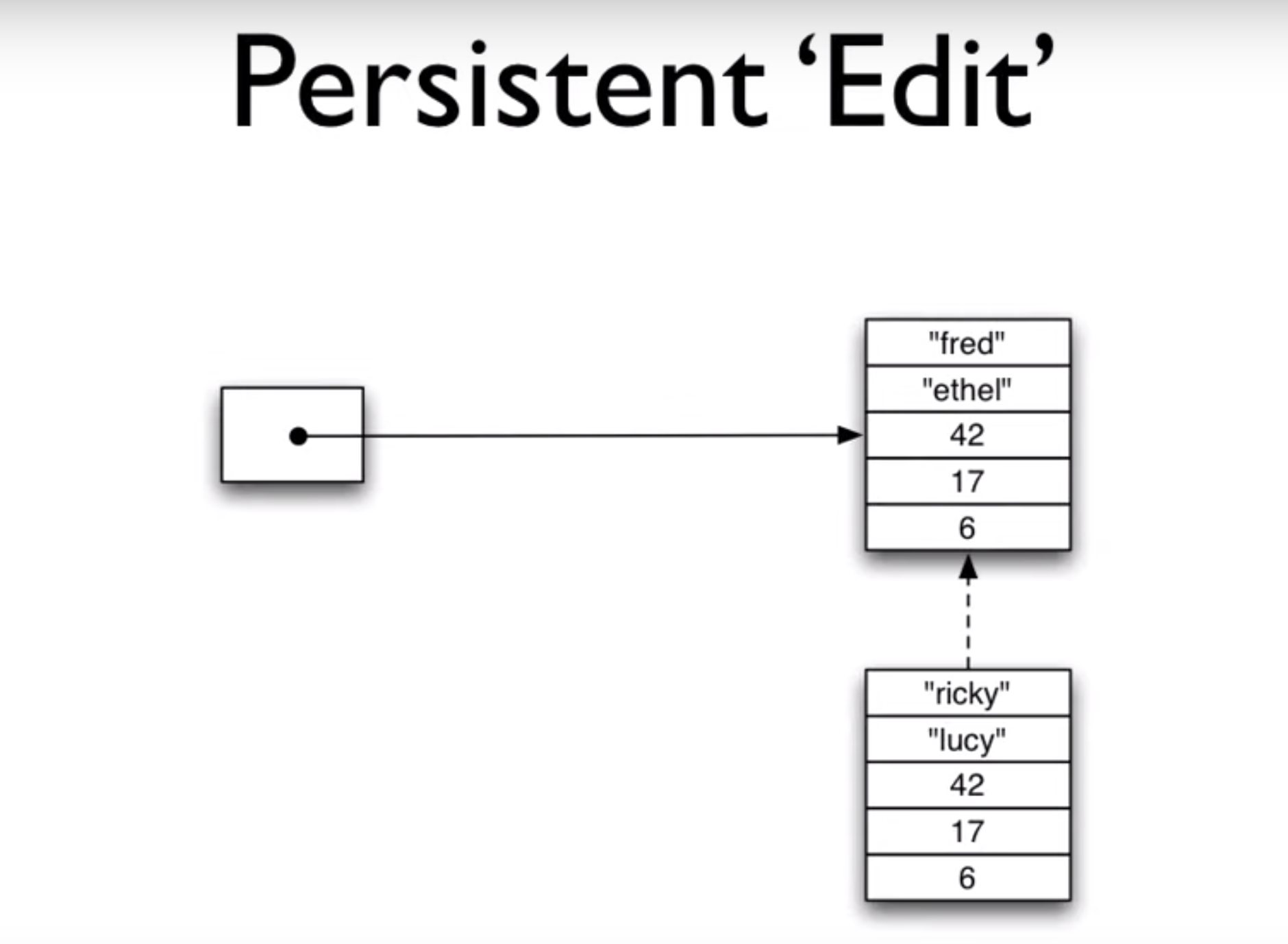

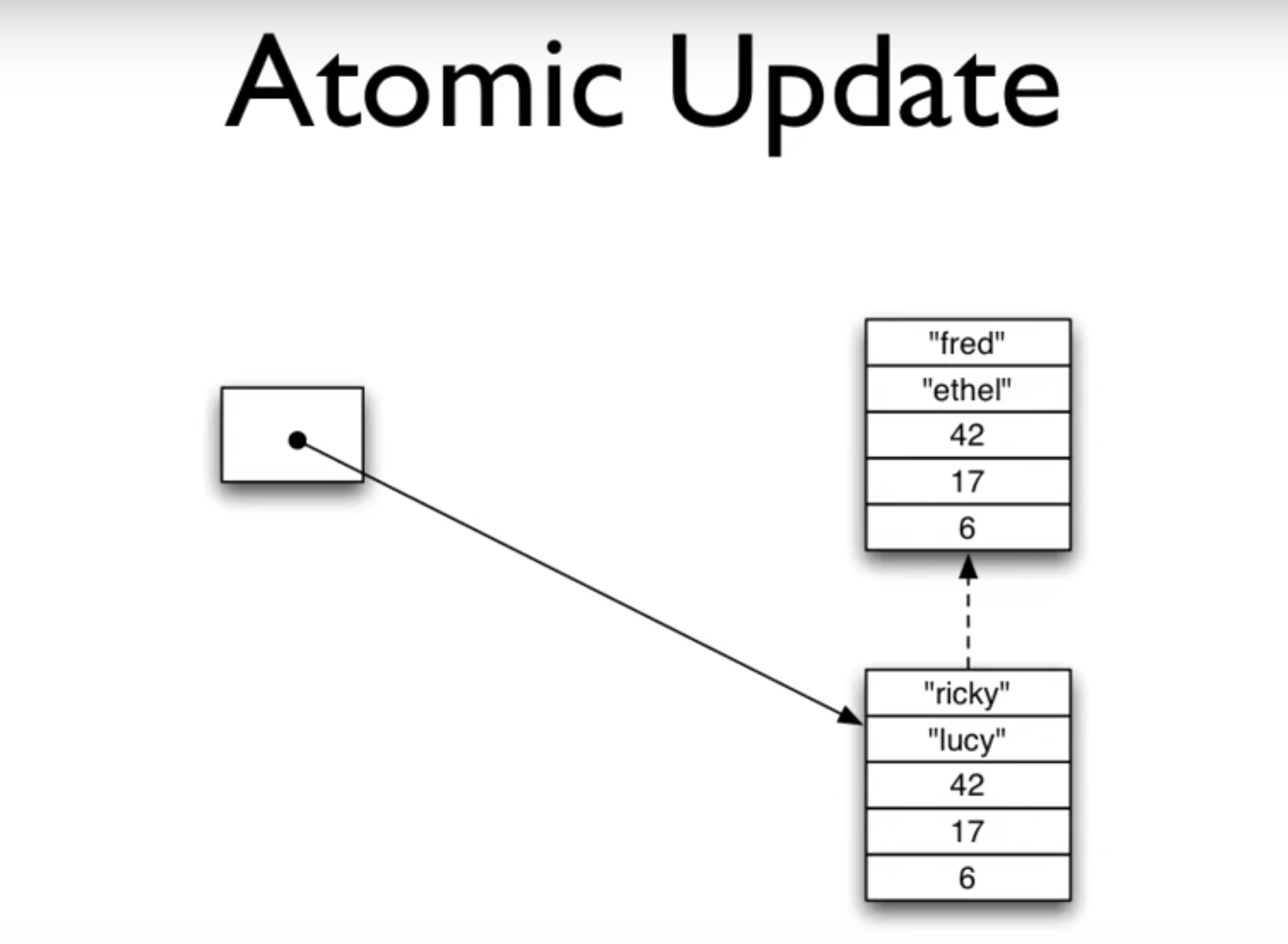

[Audience member: There is also then the part that if there are no side effects of evaluating this. In other words ...]