Library for writing beautiful, RSpec/Jasmine/Mocha/Jest-style specifications in Java, Kotlin and Groovy

This is the reference documentation for the Specnaz library. For a quick introduction to Specnaz, check out the main Readme file. For code examples, look into the src/examples directory.

- Getting Specnaz

- Writing tests

- Basic test structure - the Specnaz interface

- Framework integrations

- Calling describes

- Creating the spec

- Using Boxes

- Parametrized test support

- Using Specnaz in other JVM languages

- Framework extensions

- Extending Specnaz

Specnaz is available through the Maven Central repository. Take a look at the main Readme file on how to get it using build tools that also do dependency management (Maven, Gradle, SBT, Ivy etc.).

If you're not using a dependency manager, you need to manually download the needed JARs and put them on your classpath:

- specnaz, and one of either:

If you want to use the Kotlin integration, in addition to the ones above, you also need:

- specnaz-kotlin, and one of either:

The requirements that your tests class must fulfill are simple. There are 3 of them:

- Your test classes must implement the

org.specnaz.Specnazinterface This is an interface with one method (describes) which is default (it has an implementation), so your class doesn't need any additional code to use it. - Your test class must have a public, no-argument constructor.

- In that constructor, the

describesmethod from theorg.specnaz.Specnazinterface must be called exactly once. Thedescribesmethod is how you construct the tests (usually called 'specifications' by convention) in Specnaz. We will look at that method in more details in later chapters.

The easiest way to use Specnaz with JUnit 4 is to extend the org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnit

helper class, which already implements the Specnaz interface:

import org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnit;

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

// body of the spec here...

}If you want to extend a class other than SpecnazJUnit,

you need to specify the JUnit 4 Runner for Specnaz,

org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnitRunner,

using the @RunWith annotation:

import org.specnaz.Specnaz;

import org.junit.runner.RunWith;

@RunWith(SpecnazJUnitRunner.class)

public class StackSpec extends CommonSpec implements Specnaz {

// body of the spec here...

}To use Specnaz with TestNG, your test class needs to implement the

org.specnaz.testng.SpecnazFactoryTestNG interface, which extends org.specnaz.Specnaz

(like Specnaz, it's an interface with one default method,

so your class doesn't need any additional code to implement it),

and also needs to be annotated with TestNG's @Test annotation.

Example:

import org.specnaz.testng.SpecnazFactoryTestNG;

import org.testng.annotations.Test;

@Test

public class StackSpec implements SpecnazFactoryTestNG {

// body of the spec here...

}Note that TestNG is not as flexible as JUnit, and has some inherent limitations when used as the execution engine for Specnaz:

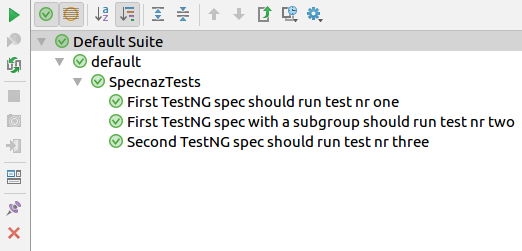

- TestNG doesn't support the same arbitrary test results trees as JUnit - which means the reports will be flattened, regardless of the level of nesting in your specs. The reported name of each test will be all of descriptions, up to the root of the spec tree, concatenated with the test's own description.

- All of the results will be reported under one root class,

org.specnaz.testng.SpecnazTests, completely discarding the name of your test class.

So, assuming you have the following 2 tests in your test suite:

@Test

public class FirstSpec implements SpecnazFactoryTestNG {{

describes("First TestNG spec", it -> {

it.should("run test nr one", () -> {

// test body here...

});

it.describes("with a subgroup", () -> {

it.should("run test nr two", () -> {

// test body here...

});

});

});

}}

@Test

public class SecondSpec implements SpecnazFactoryTestNG {{

describes("Second TestNG spec", it -> {

it.should("run test nr three", () -> {

// test body here...

});

});

}}, the results of executing them will look something like this:

To use Specnaz with JUnit 5,

the only thing you need to do is annotate your spec class with the

org.junit.platform.commons.annotation.Testable annotation:

import org.junit.platform.commons.annotation.Testable;

@Testable

public class StackSpec implements Specnaz {

// body of the spec here...

}Because the describes method needs to be called in the default constructor,

the most concise way of formulating your specification is by using Java's

'initializer blocks' feature:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

// body of the spec here...

});

}

}You can use the "double-braces" syntax as well, which saves you one level of indentation:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

// body of the spec here...

});

}}The first argument to the method is the top-level description of the spec.

As you can see, by convention, the parameter of the closure given as the

second argument, of type org.specnaz.SpecBuilder, is named it.

The methods in the SpecBuilder interface were named expecting this

convention, and sticking to it assures that your specification reads well

(it also means you will be consistent with specs written in languages

other than Java).

The specification is built by calling methods on the declared

SpecBuilder instance. They are:

The should method introduces a test.

It's the equivalent of RSpec's or Jasmine's it method.

Simple example:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

it.should("be empty when first created", () -> {

Stack<Integer> newStack = new Stack<>();

Assert.assertTrue(newStack.isEmpty());

});

});

}}You can have any number of these tests in one group:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

it.should("be empty when first created", () -> {

Stack<Integer> newStack = new Stack<>();

Assert.assertTrue(newStack.isEmpty());

});

it.should("have size 0 when first created", () -> {

Stack<Integer> newStack = new Stack<>();

Assert.assertEquals(0, newStack.size());

});

});

}}Note: Specnaz does not impose any ordering between tests in one group

(unlike with begins / ends methods,

which always execute in the same order they were defined in a group) -

in particular, they might not execute in the same order as they were written.

You should not write your tests in a way that makes them dependent on their relative order.

The descriptions you give as the first argument will become the test names in the report - except they will have the word "should" prepended to them, so formulate your descriptions with that in mind.

Note that you cannot nest should methods inside each other;

something like this:

it.should("first test", () -> {

it.should("nested test", () -> { // this is wrong!wil not work. Take a look at the describes method below if you want to

nest test contexts within each other.

This method is very similar to the should method - it also introduces a test.

The difference is that the test passes only if executing it results in an Exception

of the type passed to this method.

Example:

it.shouldThrow(ArithmeticException.class, "when dividing by zero", () -> {

int unused = 1 / 0;

});The description you give as the second argument will become the test name in the report - except it will have the words "should throw ExpectedExceptionClass" prepended to them, so formulate your descriptions with that in mind.

shouldThrow returns an instance of the org.specnaz.utils.ThrowableExpectations class,

which allows you to formulate further assertions on the thrown Exception.

Each method of that class returns either this, or another instance of the same class,

which makes chaining assertions easy. Example:

it.shouldThrow(ArithmeticException.class, "when dividing by zero", () -> {

int unused = 1 / 0;

}).withMessage("/ by zero").withoutCause();The beginsEach method introduces a test fixture that will be ran before

each should test case.

It's the equivalent of RSpec's or Jasmine's beforeEach.

You can also think of it as JUnit's @Before or TestNG's @BeforeTest.

Example:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

Stack<Integer> stack;

{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

it.beginsEach(() -> {

stack = new Stack<>();

});

it.should("be empty when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertTrue(stack.isEmpty());

});

it.should("have size 0 when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertEquals(0, stack.size());

});

});

}

}You can have any number of beginsEach fixtures in each group,

and they are guaranteed to run in the order that they were declared.

The endsEach method is analogous to beginsEach, except it runs after

each test case introduced by should.

It's the equivalent of RSpec's or Jasmine's afterEach.

You can also think of it as JUnit's @After or TestNG's @AfterTest.

Example:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<>();

{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

it.endsEach(() -> {

stack = new Stack<>();

});

it.should("be empty when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertTrue(stack.isEmpty());

});

it.should("have size 0 when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertEquals(0, stack.size());

});

});

}

}You can have any number of endsEach fixtures in each group,

and they are guaranteed to run in the order that they were declared.

The beginsAll method is similar to beginsEach,

except it runs once, before all of the should test cases.

It's the equivalent of RSpec's or Jasmine's beforeAll.

You can also think of it as JUnit's or TestNG's @BeforeClass.

Example:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

Stack<Integer> stack;

{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

it.beginsAll(() -> {

stack = new Stack<>();

});

it.should("be empty when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertTrue(stack.isEmpty());

});

it.should("have size 0 when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertEquals(0, stack.size());

});

});

}

}You can have any number of beginsAll fixtures in each group,

and they are guaranteed to run in the order that they were declared.

The endsAll method is analogous to beginsAll:

it runs once, after all of the test cases introduced by should.

It's the equivalent of RSpec's or Jasmine's afterAll.

You can also think of it as JUnit's or TestNG's @AfterClass.

Example:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<>();

{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

it.endsAll(() -> {

stack = new Stack<>();

});

it.should("be empty when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertTrue(stack.isEmpty());

});

it.should("have size 0 when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertEquals(0, stack.size());

});

});

}

}You can have any number of endsAll fixtures in each group,

and they are guaranteed to run in the order that they were declared.

The describes method is what gives Specnaz its power.

It's used to create sub-specifications,

which share their parent's fixtures.

Example:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {{

describes("A Stack", it -> {

Stack<Integer> stack = new Stack<>();

it.endsEach(() -> {

stack.clear();

});

it.should("be empty when first created", () -> {

Assert.assertTrue(stack.isEmpty());

});

it.describes("with 10 and 20 pushed on it", () -> {

it.beginsEach(() -> {

stack.push(10);

stack.push(20);

});

it.should("have size equal to 2", () -> {

Assert.assertEquals(2, stack.size());

});

it.should("have 20 as the top element", () -> {

Assert.assertEquals(20, (int)stack.peek());

});

});

});

}}You can have any number of describes methods in each group.

The nested spec can use exactly the same methods the parent one can,

including describes, which means you can create arbitrary-shaped

specification trees.

It's important to understand precisely the order in which fixtures execute in case of nested specifications. To do that, we first need to introduce the concept of groups.

A group is simply the collection of fixtures and tests on the same level of nesting in the specification tree.

That may sound a little abstract, so here's an example:

public class NestedSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {{

describes("Outer group", it -> {

it.beginsAll(() -> {

// outer group beginsAll

});

it.beginsEach(() -> {

// outer group beginsEach

});

it.endsEach(() -> {

// outer group endsEach

});

it.endsAll(() -> {

// outer group endsAll

});

it.should("outer group test 1", () -> {

// outer group test 1

});

it.should("outer group test 2", () -> {

// outer group test 2

});

it.describes("inner group", () -> {

it.beginsAll(() -> {

// inner group beginsAll

});

it.beginsEach(() -> {

// inner group beginsEach

});

it.endsEach(() -> {

// inner group endsEach

});

it.endsAll(() -> {

// inner group endsAll

});

it.should("inner group test 1", () -> {

// inner group test 1

});

it.should("inner group test 2", () -> {

// inner group test 2

});

});

});

}}This specification consists of two groups, named 'outer' and 'inner'. Each group has one of every type of fixture, and two test cases. Because they are nested, we say that 'inner' is a child group of 'outer'; conversely, 'outer' is a parent group of 'inner'.

The first, obvious rule, is that child groups have no influence on the execution of parent groups. So, the outer group will execute as follows:

Note: Specnaz does not impose any ordering between tests in the same group

(unlike with begins / ends methods in the same group,

which always execute in the same order they were defined).

In the below examples, we assume they will execute in the same order as they were written.

However, that's not guaranteed by the framework, and you shouldn't rely on it in your tests.

- outer group beginsAll

- outer group beginsEach

- outer group test 1

- outer group endsEach

- outer group beginsEach

- outer group test 2

- outer group endsEach

- outer group endsAll

In case of nested groups, the rule is fairly simple:

When a group's test cases are executed, all of the ancestor groups fixtures are executed as well.

The only difference is the order in which they are executed:

beginsAll/beginsEachexecute in 'outside-in' order - meaning, from the top-most parent down to the child group being executedendsAll/endsEachexecute in reverse order, so 'inside-out' - starting from the child group being executed up to the top-most parent group

So, the execution of the 'inner' group will look like the following:

- outer group beginsAll

- inner group beginsAll

- outer group beginsEach

- inner group beginsEach

- inner group test 1

- inner group endsEach

- outer group endsEach

- outer group beginsEach

- inner group beginsEach

- inner group test 2

- inner group endsEach

- outer group endsEach

- inner group endsAll

- outer group endsAll

If you have experience with similar testing tools in other languages, like RSec and Jasmine, you might notice that Specnaz behaves differently here.

In RSpec and Jasmine, the child groups do not execute their parent's

beforeAll/afterAll callbacks again.

They are executed only once, when that group's test cases are ran

(the afterAll ones when the last child group is finished).

Both ways of executing the fixtures make sense, and both are useful under different circumstances. They are also equivalent - you can express one in terms of the other.

The reason for doing it this way is that Specnaz was designed for Java. And in Java, while it's fairly easy to go from the Specnaz way to the RSpec/Jasmine way, it's much harder to go in the opposite direction. Let me illustrate.

Let's say we have the following Jasmine spec:

describe("outer group", function () {

beforeAll(function () {

// beforeAll setup...

});

it("outer test", function () {

// outer group test

});

describe("inner group", function () {

it("inner test", function () {

// inner group test

});

});

});The beforeAll setup will run only once, right before the outer test,

and not again before inner test.

If we wanted to achieve the same in Specnaz, it would be fairly straightforward:

public class BeforeAllOnceSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

boolean setupRan = false;

{

describes("outer group", it -> {

it.beginsAll(() -> {

if (!setupRan) {

setupRan = true;

// beforeAll setup...

}

});

it.should("outer test", () -> {

// outer group test

});

it.describes("inner group", () -> {

it.should("inner test", () -> {

// inner group test

});

});

});

}

}However, imagine the opposite - that we wanted to have the Specnaz behavior in the Jasmine spec. It would look something like the following:

describe("outer group", function () {

function init() {

// beforeAll setup...

}

beforeAll(function () {

init();

});

it("outer test", function () {

// outer group test

});

describe("inner group", function () {

beforeAll(function () {

init();

});

it("inner test", function () {

// inner group test

});

});

});While this is easy to achieve in JavaScript, in Java, we don't have nested methods, which makes it a lot more cumbersome. We can use objects and lambda expressions to simulate JavaScript's local functions, but that is a lot more awkward and less readable, both for the definition and then later for the usage. We can use instance methods on the test class itself, but that means we can't define them on the level that they are actually used, and they won't have access to the variables of the closure.

For these reasons, Specnaz changes the traditional behavior of the

beginsAll and endsAll fixtures.

If you need to perform some setup and/or teardown that should happen once per class (and not once per group), you can achieve that using the JUnit 4 Class Rules API that Specnaz supports natively.

fshould is a way to temporary mark a given should test as 'focused'.

This works exactly like in RSpec and Jasmine.

If a class contains at least one focused test, then only focused tests will be ran when it is executed -

unfocused (that is, created with should) tests will be ignored.

This is useful when wanting to run and debug a single test in a class -

it's easy to run a single test when using 'vanilla' JUnit, but quite hard with Specnaz

(the IDEs and build tools were not really designed for tree-based tests).

With this method, you can simply add an 'f' in front of a call to should,

and the next time this spec class is ran, only the fshould tests will actually be executed.

Naturally, all of the fixtures

(beginsAll/Each and endsAll/Each) in the tree will be executed,

just like for regular, 'unfocused' tests -

including fixtures from parent groups whose tests were all ignored

because of not being focused. Example:

class FocusedSpec {

int counter = 1;

{

describes("A focused test", it -> {

it.beginsAll(() -> {

counter++;

});

it.should("not run this test", () -> {

Assert.fail("this should not be executed");

});

it.describes("with a focused subgroup", () -> {

it.fshould("run this test", () -> {

Assert.equals(2, counter);

});

});

});

}

}This method is deprecated, as it's only meant as a temporary stop gap to aid you in debugging a failing test - it's not meant to be part of the test suite permanently. Deprecating it means there is a higher chance you notice it, and remember to remove the 'f' at the beginning before committing the change to source control.

This is the focused equivalent of shouldThrow.

The thinking behind this method is the same as behind fshould,

and it's deprecated for exactly the same reason.

This is the focused equivalent of describes.

All tests present in this focused group

(including subgroups of this group) will be focused,

even if defined with regular should and describes calls

instead of fshould and fdescribes.

xshould is a way to ignore the given test.

This works exactly like in RSpec and Jasmine.

If you ever need to ignore a test for any reason, instead of fiddling with commenting out code,

simply add an 'x' in front of the call to should,

and this specific test will not be executed.

This is the shouldThrow equivalent of xshould -

ignores a test expecting an Exception.

xdescribes allows you to ignore an entire subtree of tests

(including sub-specifications defined with describes).

Note: there is also an xdescribes at the top level

(the one that you call in the constructor) - in that case,

all of the specifications in the class will be skipped.

One awkward part of writing specs in Java is the limitation that inside the lambda expression, you can only reference final and effectively final variables of the enclosing scope. We often want to write something like this:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {{

Stack<Integer> stack;

describes("A Stack", it -> {

it.beginsEach(() -> {

stack = new Stack<>(); // not valid in Java!

});

// rest of the spec here...

});

}}We can work around this by using instance variables of the test class, like we have been in these examples. However, that means we can't use the "double braces" syntax, meaning we need to have the code indented an extra level, and, even worse, we have to define all of the local test variables at the same level, instead of doing it where they are actually used, making our tests less readable.

To help with this use-case, Specnaz ships with a utility class -

org.specnaz.utils.Box, which is a very simple wrapper around any value,

which is kept in a public field, called $.

This way, the reference to the Box class is final,

but the value of the field can be mutated at will.

Here is a simple example:

public class StackSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {{

Box<Stack<Integer>> stack = Box.emptyBox();

describes("A Stack", it -> {

it.beginsEach(() -> {

stack.$ = new Stack<>();

});

it.should("be empty when first created", () -> {

assertThat(stack.$).isEmpty();

});

});

}}For readability, and to leverage Java's type inference, Box has a

private constructor - you create instances of it using static factory

methods, emptyBox and boxWith.

There are also equivalent classes for boxing primitive values

(int, bool, long etc.), named IntBox, BoolBox, LongBox etc.

Specnaz has built-in support for writing parametrized tests.

In order to get access to the parametrized tests capabilities,

you need to implement the org.specnaz.params.SpecnazParams

interface in your test class instead of the regular Specnaz one.

There is a helper class, org.specnaz.params.junit.SpecnazParamsJUnit,

which is analogous to the regular SpecnazJUnit helper, that you can extend:

import org.specnaz.params.junit.SpecnazParamsJUnit;

public class MyParametrizedSpec extends SpecnazParamsJUnit {

// body of the spec here...

}If you're implementing the interface directly,

you provide the same Runner with the @RunWith annotation,

SpecnazJUnitRunner, as you would for regular (non-parametrized) tests:

import org.junit.runner.RunWith;

import org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnitRunner;

import org.specnaz.params.SpecnazParams;

@RunWith(SpecnazJUnitRunner.class)

public class MyParametrizedSpec extends MyParent implements SpecnazParams {

// body of the spec here...

}When using TestNG as the execution engine, to create parametrized tests,

you need to make your test class implement the org.specnaz.params.testng.SpecnazParamsFactoryTestNG

interface instead of the regular SpecnazFactoryTestNG one

(SpecnazParamsFactoryTestNG extends SpecnazParams,

so you just need to implement the one interface).

Also, just as with regular tests,

your class needs to be annotated with the @Test annotation.

Example:

import org.specnaz.params.testng.SpecnazParamsFactoryTestNG;

import org.testng.annotations.Test;

@Test

public class MyParametrizedSpec implements SpecnazParamsFactoryTestNG {

// body of the spec here...

}The only difference between regular and parametrized tests when using JUnit 5 as the test execution engine

is the need to implement the SpecnazParams interface instead of Specnaz:

import org.junit.platform.commons.annotation.Testable;

import org.specnaz.params.SpecnazParams;

@Testable

public class MyParametrizedSpec implements SpecnazParams {

// body of the spec here...

}The way you define parametrized tests is very similar to regular, non-parametrized ones.

The difference is that instead of passing a no-argument lambda

as the body of the test to a should or shouldThrow method,

you instead pass a lambda expecting between one and nine arguments.

You use these arguments in your test case as parameters,

and then call the provided method on the object should or shouldThrow returns.

The provided method is used to specify with what parameters should the tests run.

The parameters are given by passing instances of the ParamsX class,

where X is the arity of the lambda passed to should or shouldThrow -

so, if you passed a two-argument lambda, you need to provide instances of the Params2 class.

Each of the ParamsX classes contains a static factory method named pX

used for concisely constructing instances of it (so, Params2 has p2, Params3 - p3, etc.).

The provided method is overloaded, so that you can supply the ParamsX

instances directly, using variadic arguments,

or through a Collection of the appropriate ParamsX type.

Each instance of a ParamsX class you provide will result in a separate test being executed and reported.

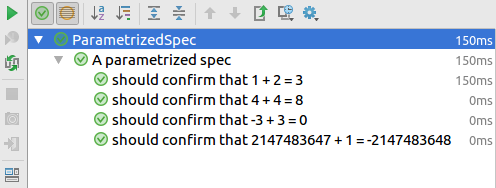

Example:

import org.specnaz.params.junit.SpecnazParamsJUnit;

import static org.specnaz.params.Params3.p3;

public class ParametrizedSpec extends SpecnazParamsJUnit {{

describes("A parametrized spec", it -> {

it.should("confirm that %1 + %2 = %3", (Integer a, Integer b, Integer c) -> {

assertThat(a + b).isEqualTo(c);

}).provided(

p3(1, 2, 3),

p3(4, 4, 8),

p3(-3, 3, 0),

p3(Integer.MAX_VALUE, 1, Integer.MIN_VALUE)

);

});

}}Because we gave a 3-parameter lambda to should,

we need to call provided with instances of Params3.

As we gave four instances in the call,

this will result in 4 tests being executed.

We also used the special placeholders in the description string: %1, %2, etc.

These will be expanded at runtime by the library with the values

of the parameters at the appropriate index, counting from 1.

So, the spec above will look like this when executed:

There is a slight difference when the lambda you provided to should or shouldThrow

takes only one argument

(in other words, for a parametrized test with a single parameter).

In that case, there is no Params1 class -

you just provide the values directly, either as variadic arguments,

or as a Collection.

Example:

it.shouldThrow(NumberFormatException.class, "when trying to parse '%1' as an Int", (String str) -> {

Integer.parseInt(str);

}).provided("a", "b");The provided methods return objects of the same type that regular,

non-parametrized tests would - so, TestSettings for should,

and ThrowableExpectations for shouldThrow.

Which means we could have expanded the above example with some additional

assertions on the thrown Exception as follows:

it.shouldThrow(NumberFormatException.class, "when trying to parse '%1' as an Int", (String str) -> {

Integer.parseInt(str);

}).provided("a", "b").withoutCause();The TestSettings and ThrowableExpectations objects returned by provided

are shared between all instances of the tests when they are expanded with parameters.

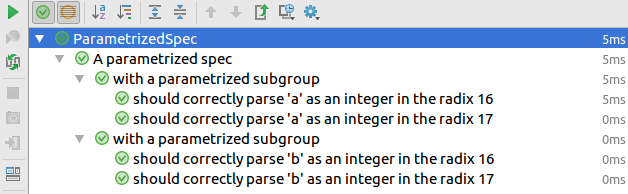

You can also provide a lambda with arguments to the describes method,

in that way creating a parametrized sub-specification.

It behaves exactly like you would expect:

you need to call the provided method on the object the parametrized describes returns,

exactly like for parametrized should and shouldThrow,

and there will be a separate sub-specification created for each instance of the appropriate ParamsX

class that you provide in that call.

Note: you can use the String.format method to dynamically set the descriptions of the tests

inside the sub-specification, depending on the value(s) of the parameters.

But if you want to combine that with the placeholders Specnaz expands,

remember that you need to escape the % character in the call to format

by writing a double percent. So, the placeholder would look something like %%1 in that case.

For example, this specification:

it.describes("with a parametrized subgroup", (String str) -> {

it.should(format("correctly parse '%s' as an integer in the radix %%1", str), (Integer radix) -> {

Integer.parseInt(str, radix);

}).provided(16, 17);

}).provided("a", "b");will result in the following tests tree:

You can also focus and ignore parametrized tests and sub-specifications.

It works exactly like for non-parametrized tests -

simply add an f or an x in front of a call to define a parametrized test or sub-specification,

and all tests that will be executed as a result of it will be focused or ignored.

Specnaz has first-class support for writing specs in Kotlin.

You can use the Java Specnaz classes from Kotlin without any problems:

class StackJavaSpec : SpecnazJUnit() { init {

describes("A Stack") {

var stack = Stack<Int>()

it.endsEach {

stack = Stack()

}

it.should("be empty when first created") {

Assert.assertTrue(stack.isEmpty())

}

it.describes("with 10 and 20 pushed on it") {

it.beginsEach {

stack.push(10)

stack.push(20)

}

it.should("have size equal to 2") {

Assert.assertEquals(2, stack.size)

}

it.should("have 20 as the top element") {

Assert.assertEquals(20, stack.peek())

}

}

}

}}As you can see, the Kotlin test is very similar to the Java one, but looks

a little better - there is less punctuation (semicolons are gone, the parenthesis

can be closed after the first argument or omitted entirely, as Kotlin allows

you to give the lambda expression outside of them if it's the last parameter)

and you don't have to name the parameter to the lambda given as the second

argument to the describes method - Kotlin automatically binds it to the

it variable.

Kotlin also doesn't have the limitation that variables referenced in closures

must be final or effectively final, which means you don't have to use the

Box classes.

While the Java bindings do work with Kotlin,

Specnaz also ships with alternative versions of the core APIs,

written in Kotlin and designed specifically to be consumed from that language.

So, we have org.specnaz.kotlin.SpecnazKotlin

instead of org.specnaz.Koltin,

and org.specnaz.kotlin.KotlinSpecBuilder

instead of org.specnaz.SpecBuilder.

These classes and interfaces live in the specnaz-kotlin library.

The methods in the Kotlin version are named exactly the same as their Java counterparts;

the main difference is that they have signatures more idiomatic for Kotlin consumption.

For instance, KotlinSpecBuilder defines its own versions of all of the spec building methods like should,

beginsEach, describes etc., with signatures using the Kotlin function types

instead of the org.specnaz.utils.TestClosure functional interface that Java uses.

This is better in 2 ways:

- the IDE support is better (for example, Intellij lists each

method of the

org.specnaz.SpecBuildertwice in the auto-completion menu when using it from Kotlin, once with the Kotlin function signature and once with theTestClosuresignature, which is irritating) - you get better type-safety, as all of the redefined fixture functions

(

beginsAll/each,endsAll/each) take aNothing?(Kotlin's equivalent of Java'sVoid) as their first argument, which means that if you didn't override the default name of lambda parameter (it), the type system will not allow you to do illegal things when building the spec (like callingshouldfrom inside abeginsEach).

Another difference is the shouldThrow method.

While in Java, you pass an instance of java.lang.Class

as the first parameter to shouldThrow,

in Kotlin, thanks to reified generics,

you pass the type of the expected Exception as a type parameter when calling the method.

Example:

it.shouldThrow<ArithmeticException>("when dividing by zero") {

1 / 0

}Just as there is a Kotlin version of the core library, there are also Kotlin-specific versions of the libraries that integrate Specnaz with test execution engines, like JUnit and TestNG:

The Kotlin JUnit 4 support lives in the specnaz-kotlin-junit library

(which has a dependency on specnaz-kotlin).

There is a Kotlin equivalent of the org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnit class,

org.specnaz.kotlin.junit.SpecnazKotlinJUnit:

import org.specnaz.kotlin.junit.SpecnazKotlinJUnit

import org.junit.Assert

import java.util.Stack

class StackKotlinSpec : SpecnazKotlinJUnit("A Stack", {

var stack = Stack<Int>()

it.endsEach {

stack = Stack()

}

it.should("be empty when first created") {

Assert.assertTrue(stack.isEmpty())

}

it.describes("with 10 and 20 pushed on it") {

it.beginsEach {

stack.push(10)

stack.push(20)

}

it.should("have size equal to 2") {

Assert.assertEquals(2, stack.size)

}

it.should("have 20 as the top element") {

Assert.assertEquals(20, stack.peek())

}

}

})As you can see, SpecnazKotlinJUnit calls the describes method

from the SpecnazKotlin interface in its primary constructor,

which means you can save one level of indentation

(and a little boilerplate)

when your spec class doesn't need to extend a particular class.

If your spec class does need to extend a particular class,

you have to provide the Kotlin JUnit 4 Runner,

org.specnaz.kotlin.junit.SpecnazKotlinJUnitRunner,

instead of the Java SpecnazJUnitRunner,

with JUnit's @RunWith annotation:

import org.specnaz.kotlin.SpecnazKotlin

import org.specnaz.kotlin.junit.SpecnazKotlinJUnitRunner

import org.junit.runner.RunWith

@RunWith(SpecnazKotlinJUnitRunner::class)

class StackKotlinSpec : SpecCommon(), SpecnazKotlin { init {

describes("A Stack") {

// spec body...

}

}}If you want to ignore an entire class of specs,

and that class inherits from SpecnazKotlinJUnit,

you can't simply use the xdescribes method call,

as that code is buried in the SpecnazKotlinJUnit constructor.

To help with that case, there is a class called xSpecnazKotlinJUnit in the same,

org.specnaz.kotlin.junit, package.

With that, you can simply add an 'x' in front of SpecnazKotlinJUnit,

and with that one change ignore all of the specs defined in that class.

The Kotlin TestNG support lives in the specnaz-kotlin-testng library

(which has a dependency on specnaz-kotlin).

It contains an equivalent of the SpecnazKotlinJUnit class,

org.specnaz.kotlin.testng.SpecnazKotlinTestNG:

import org.specnaz.kotlin.testng.SpecnazKotlinTestNG

import org.testng.Assert

import org.testng.annotations.Test

import java.util.Stack

@Test

class StackKotlinSpec : SpecnazKotlinTestNG("A Stack", {

var stack = Stack<Int>()

it.endsEach {

stack = Stack()

}

it.should("be empty when first created") {

Assert.assertTrue(stack.isEmpty())

}

it.describes("with 10 and 20 pushed on it") {

it.beginsEach {

stack.push(10)

stack.push(20)

}

it.should("have size equal to 2") {

Assert.assertEquals(stack.size, 2)

}

it.should("have 20 as the top element") {

Assert.assertEquals(stack.peek(), 20)

}

}

})Exactly like SpecnazKotlinJUnit,

SpecnazKotlinTestNG allows you to save one level of indentation

(and a little boilerplate)

when your spec class doesn't need to extend a particular class.

If your spec class does need to extend a particular class,

you can implement the org.specnaz.kotlin.testng.SpecnazKotlinFactoryTestNG

interface instead of the Java SpecnazFactoryTestNG one.

SpecnazKotlinFactoryTestNG extends SpecnazKotlin,

and gives you the idiomatic Kotlin experience in your TestNG specs:

import org.specnaz.kotlin.testng.SpecnazKotlinFactoryTestNG

import org.testng.annotations.Test

@Test

class StackKotlinSpec : SpecCommon(), SpecnazKotlinFactoryTestNG { init {

describes("A Stack") {

// spec body...

}

}}Similarly to xSpecnazKotlinJUnit above,

there's also an org.specnaz.kotlin.testng.xSpecnazKotlinTestNG

class for ignoring an entire specification extending from

SpecnazKotlinTestNG.

The Kotlin JUnit 5 support lives in the specnaz-kotlin-junit-platform library

(which has a dependency on specnaz-kotlin).

There is a Kotlin equivalent of the org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnit class,

org.specnaz.kotlin.junit.platform.SpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatform:

import org.specnaz.kotlin.junit.platform.SpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatform

import java.util.Stack

import org.assertj.core.api.Assertions.assertThat

class StackKotlinSpec : SpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatform("A Stack", {

var stack = Stack<Int>()

it.endsEach {

stack = Stack()

}

it.should("be empty when first created") {

assertThat(stack).isEmpty()

}

it.describes("with 10 and 20 pushed on it") {

it.beginsEach {

stack.push(10)

stack.push(20)

}

it.should("have size equal to 2") {

assertThat(stack).hasSize(2)

}

it.should("have 20 as the top element") {

assertThat(stack.peek()).isEqualTo(20)

}

}

})As you can see, SpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatform calls the describes method

from the SpecnazKotlin interface in its primary constructor,

which means you can save one level of indentation

(and a little boilerplate)

when your spec class doesn't need to extend a particular class.

If your spec class does need to extend a particular class,

you need to implement the SpecnazKotlin interface,

and annotate your class with the org.junit.platform.commons.annotation.Testable annotation:

import org.junit.platform.commons.annotation.Testable

import org.specnaz.kotlin.SpecnazKotlin

@Testable

class StackKotlinSpec : SpecCommon(), SpecnazKotlin { init {

describes("A Stack") {

// spec body...

}

}}If you want to ignore an entire class of specs,

and that class inherits from SpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatform,

you can't simply use the xdescribes method call,

as that code is buried in the SpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatform constructor.

To help with that case, there is a class called xSpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatform in the same,

org.specnaz.kotlin.junit.platform, package.

With that, you can simply add an 'x' in front of SpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatform,

and with that one change ignore all of the specs defined in that class.

One irritating thing about writing tests in Kotlin is that the compiler

checks both for null values and forces variables to be always initialized

before being used. That's of course great in production code, but gets

tedious in tests. For example:

class KotlinSpec : SpecnazKotlinJUnit("A spec", {

var someDomainClass: MyDomainClass

it.beginsEach {

someDomainClass = myDomainOperation()

}

it.should("do something properly") {

Assert.assertTrue(someDomainClass.something()); // does not compile!

}

})The above snippet will not work - the compiler will complain that

someDomainClass must be initialized before being used.

The easiest way to solve this problem is to use the lateinit modifier -

so, simply replace var someDomainClass: MyDomainClass above with

lateinit var someDomainClass: MyDomainClass.

However, that's allowed on local variables only with Kotlin version 1.2 or later -

before that lateinit was limited to class attributes.

If you're on a version of Kotlin before 1.2,

you can still use local variables instead of class attributes in this case

by leveraging a simple helper class that ships with Specnaz,

org.specnaz.kotlin.utils.Deferred.

You use it like so:

class KotlinSpec : SpecnazKotlinJUnit("A spec", {

val someDomainClass = Deferred<MyDomainClass>()

it.beginsEach {

someDomainClass.v = myDomainOperation()

}

it.should("do something properly") {

Assert.assertTrue(someDomainClass.v.something());

}

})The value of the appropriate type will be stored in the v

public instance variable of the Deferred class, and you can use it

without explicitly initializing it first, which means the above code will

compile.

If you're willing to use inheritance (Deferred is an open class),

you can make your tests read even better:

class KotlinSpec : SpecnazKotlinJUnit("A spec", {

val someDomainClass = object : Deferred<MyDomainClass>() {

val something: Boolean get() = v.something

}

it.beginsEach {

someDomainClass.v = myDomainOperation()

}

it.should("do something properly") {

Assert.assertTrue(someDomainClass.something()); // notice no '.v'

}

})Kotlin has its own version of the parametrized Specnaz interface (SpecnazParams) -

org.specnaz.kotlin.params.SpecnazKotlinParams.

There are also analogous versions of the test execution engine integrations:

- For JUnit 4, you can either extend the

org.specnaz.kotlin.params.junit.SpecnazKotlinParamsJUnitclass (an analogous class toorg.specnaz.kotlin.junit.SpecnazKotlinJUnitfor non-parametrized tests), or implement theSpecnazKotlinParamsinterface directly - in that case, you provide the same JUnit 4 Runner as for non-parametrized specs with the@RunWithannotation,org.specnaz.kotlin.junit.SpecnazKotlinJUnitRunner. If you're extendingSpecnazKotlinParamsJUnit, there's alsoxSpecnazKotlinParamsJUnitin the same package if you ever need to ignore an entire parametrized specification. - For TestNG, you can either extend the

org.specnaz.kotlin.params.testng.SpecnazKotlinParamsTestNGclass (an analogous class toorg.specnaz.kotlin.testng.SpecnazKotlinTestNGfor non-parametrized tests), or implement theorg.specnaz.kotlin.params.testng.SpecnazKotlinParamsFactoryTestNGinterface directly (an analogous interface toorg.specnaz.kotlin.testng.SpecnazKotlinFactoryTestNGfor non-parametrized tests). In both cases, your spec class needs to be annotated with TestNG's@Testannotation. If you're extendingSpecnazKotlinParamsTestNG, there's alsoxSpecnazKotlinParamsTestNGin the same package if you ever need to ignore an entire parametrized specification. - For JUnit 5, you can either extend the

org.specnaz.kotlin.params.junit.platform.SpecnazKotlinParamsJUnitPlatformclass (an analogous class toorg.specnaz.kotlin.junit.platform.SpecnazKotlinJUnitPlatformfor non-parametrized tests), or implement theSpecnazKotlinParamsinterface directly - in that case, you need to annotate your class with theorg.junit.platform.commons.annotation.Testableannotation. If you're extendingSpecnazKotlinParamsJUnitPlatform, there's alsoxSpecnazKotlinParamsJUnitPlatformin the same package if you ever need to ignore an entire parametrized specification.

Other than that, parametrized tests in Kotlin are basically the same as in Java:

pass a lambda expression with up to nine arguments to should,

use them inside the test, and then call provided on the object returned from should.

Example:

class KotlinParametrizedSpec : SpecnazKotlinParamsJUnit("A parametrized spec", {

it.should("confirm that %1 + %2 = %3") { a: Int, b: Int, c: Int ->

assertThat(a + b).isEqualTo(c)

}.provided(

p3(1, 2, 3),

p3(4, 4, 8),

p3(-3, 3, 0),

p3(Int.MAX_VALUE, 1, Int.MIN_VALUE)

)

})The one difference can be when writing parametrized shouldThrow tests.

Because in the Kotlin version of that method,

you specify the expected Exception as a type parameter,

and not an instance of the Class type,

you also have to specify the types of the parameters

of the lambda you passed as the test body.

Because of that, you don't have to repeat the types in the lambda itself.

Like this:

it.shouldThrow<NumberFormatException, String>("when parsing '%1' as an Int") { str ->

Integer.parseInt(str)

}.provided("b", "c")You can use the Specnaz from Groovy without any special bindings. Check out the Readme file of the Groovy examples for more info.

Specnaz supports the JUnit 4 Rules API natively. The integration looks a tiny bit different than in 'vanilla' JUnit 4, mostly because of the different object lifecycle (in 'vanilla' JUnit 4, each test executes with its own instance of the test class; in Specnaz, all tests share the same object instance). However, the basic idea is exactly the same.

JUnit 4 supports 2 types of Rules: class Rules (those annotated with @ClassRule) and instance Rules (those annotated with @Rule). Both of them are supported in Specnaz.

Let's start with class Rules, as they are simpler.

Class Rules work pretty much exactly the same as 'vanilla' JUnit 4.

It's a public, static field of the test class,

annotated with @ClassRule.

Note: 'vanilla' JUnit 4 also allows class Rules returned by (static) methods.

This is not supported by Specnaz.

Example:

import org.junit.ClassRule;

import org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnit;

import org.springframework.test.context.junit4.rules.SpringClassRule;

public class SpringSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

@ClassRule

public static final SpringClassRule springClassRule = new SpringClassRule();

{

describes("A Spring spec", it -> {

// spec body here...

});

}

}The Rule works exactly the same like in 'vanilla' JUnit:

it wraps the execution of the entire test class

(that is, it's executed even before any beginsAll methods).

Because of that, it's a good place to put any setup or cleanup

that you want to be executed exactly once for the whole class

(and not, like beginsAll / endsAll methods, for every nested subgroup).

Probably the easiest way to do that is to extend the

ExternalResource

Rule that ships with JUnit 4.

Example:

import org.junit.ClassRule;

import org.junit.ExternalResource;

import org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnit;

public class SomeSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

@ClassRule

public static final ExternalResource fixture = new ExternalResource() {

protected void before() {

// set up here...

}

protected void after() {

// ...and tear down here

}

};

{

describes("A spec", it -> {

// spec body here...

});

}

}If you want to have multiple class Rules in the same class, it's important to know that the order in which they will be chained is unspecified - it won't necessarily be the same order that they were declared in in source code. If you need to control that ordering, you should use the RuleChain class that ships with JUnit 4.

Instance Rules work a little bit differently than in 'vanilla' JUnit 4.

Instead of annotating fields with @Rule,

you use the class org.specnaz.junit.rules.Rule.

Every public, non-static field of the test class of this type will be picked up by the Runner,

and included in your tests.

Note: similarly as with class Rules, 'vanilla' JUnit 4 allows you to have instance Rules returned by methods. This is also not supported by Specnaz.

You create instances of Rule by calling the of static factory method,

passing in a lambda expression that returns your Rule.

The Runner will execute your lambda before each test,

this way ensuring that each test has a fresh copy of the Rule -

in other words, instance Rules obey the same lifecycle as beginsEach / endsEach methods.

You access the current instance of the Rule by using the r() method.

Example:

import org.junit.rules.ExpectedException;

import org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnit;

import org.specnaz.junit.rules.Rule;

public class ExpectedExceptionRuleSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

public Rule<ExpectedException> expectedException = Rule.of(() -> ExpectedException.none());

{

describes("Using the ExpectedException JUnit Rule in Specnaz", it -> {

it.should("correctly set the expected Exception", () -> {

expectedException.r().expect(IllegalArgumentException.class);

throw new IllegalArgumentException();

});

});

}

}The same remark about multiple class Rules applies to instance Rules as well - if you need control over the order in which multiple instance Rules in the same class are applied, use the RuleChain class that ships with JUnit 4.

Some JUnit Rules recognize certain annotations placed on the test method in a 'vanilla' JUnit 4 test class (it's quite common in Spring, for example - see here for a list of recognized annotations). This is tricky in Specnaz, as tests are defined through method calls, not method declarations, and you can't place annotations on calls.

For that reason, the should method returns an instance of a class, org.specnaz.TestSettings,

that allows you to set a custom method for a Specnaz test by calling its

usingMethod(java.lang.reflect.Method) method.

The provided Method will be passed to all instance JUnit 4 Rules defined in this class.

Because obtaining method instances is somewhat cumbersome in Java,

Specnaz includes a utility method that helps with that,

org.specnaz.utils.Utils.findMethod.

Example usage:

import org.specnaz.junit.SpecnazJUnit;

import org.specnaz.utils.Utils;

import org.springframework.test.annotation.DirtiesContext;

public class SomeSpringSpec extends SpecnazJUnit {

{

describes("some example tests", it -> {

it.should("correctly find the method", () -> {

// test body...

}).usingMethod(Utils.findMethod(this, "someMethod"));

});

}

@DirtiesContext

public void someMethod() {

}

}Note: because the shouldThrow method returns an instance of a different class (ThrowableExpectations),

you can't call usingMethod for tests defined using shouldThrow.

If you need to combine a JUnit 4 Rule with an exception throwing test that requires annotations on the method,

you have to use should and some alternative mechanism of specifying the exception, such as:

- CatchException

- If you're using AssertJ for assertions, you have a lot of options

- The ExpectedException Rule that ships with JUnit 4

- You can always use an explicit

try-catchinside theshouldtest

Check out the specnaz-junit-rules-examples subproject - it contains examples of Specnaz specs using various Rules, both those that ship with the standard JUnit 4 distribution, as well as third-party Rules from Mockito, Spring and Dropwizard.

Specnaz allows you to extend it by creating your own DSL

(Domain-Specific Language) for tests.

In fact, the begins/ends/should DSL that you've seen used in this

documentation is not built-in into the framework -

it's created using the core Specnaz API, which the library clients can use as well.

Take a look at the specnaz-custom-dsl-example project Readme file for documentation and a working example of how to extend Specnaz.