For Cherise Irons, chocolate, red wine, and aged cheeses are dangerous. So are certain sounds, perfumes and other strong scents, cold weather, and thunderstorms. Stress and lack of sleep, too.

She suspects all of these things can trigger her migraine attacks, which manifest in a variety of ways: pounding pain in the back of her head, exquisite sensitivity to the slightest sound, even blackouts and partial paralysis.

Irons, 48, of Coral Springs, Florida, once worked as a school assistant principal. Now, she’s on disability due to her migraine. Irons has tried so many migraine medications she’s lost count—but none has helped for long. Even a few of the much-touted new drugs that have quelled episodes for many people with migraine have failed for Irons.

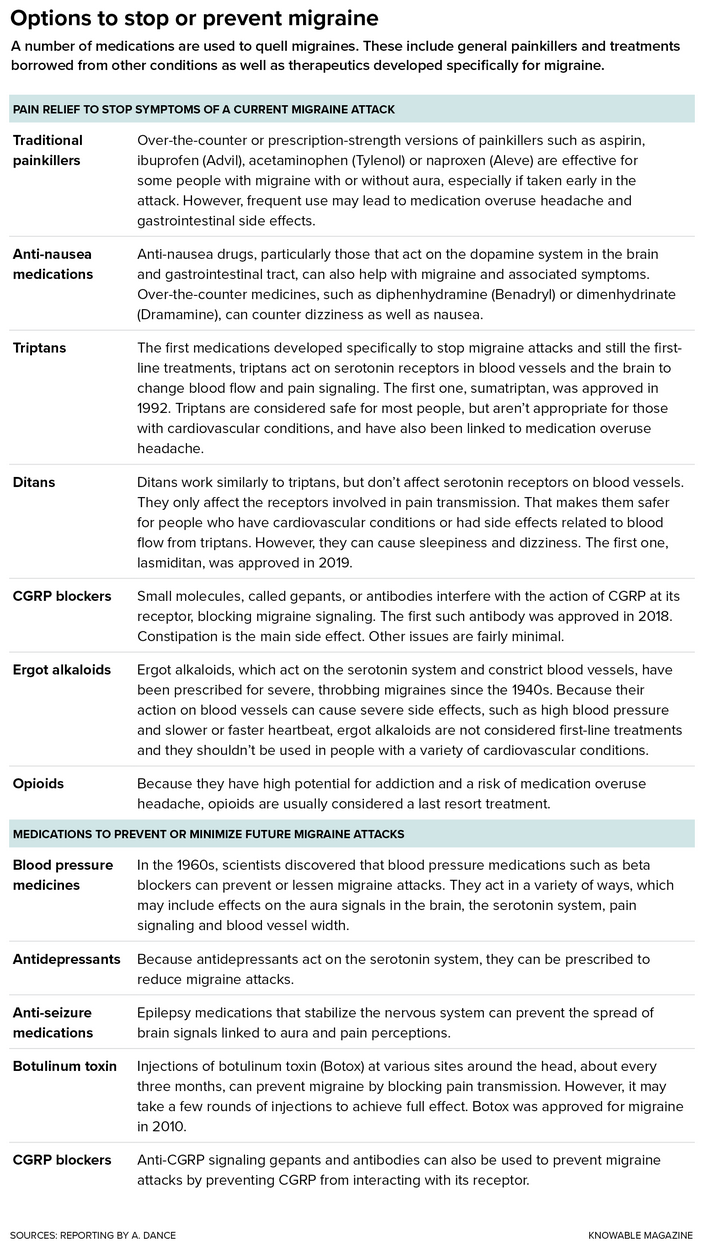

Though not all are as impaired as Irons, migraine is a surprisingly common problem, affecting 14 percent to 15 percent of people. Yet scientists and physicians remain largely in the dark about how triggers like Irons’ lead to attacks. They have made progress nonetheless: The latest drugs, inhibitors of a body signaling molecule called CGRP, have been a blessing for many. For others, not so much. And it’s not clear why.

The complexity of migraine probably has something to do with it. “It’s a very diverse condition,” says Debbie Hay, a pharmacologist at the University of Otago in Dunedin, New Zealand. “There’s still huge debate as to what the causes are, what the consequences are.”

That’s true despite decades of research and the remarkable ability of scientists to trigger migraine attacks in the lab: Giving CGRP intravenously to people who get migraines gives some of them attacks. So do nitric oxide, a natural body molecule that relaxes blood vessels, and another signaling molecule called PACAP. In mice, too, CGRP and PACAP molecules can bring on migraine-like effects.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...