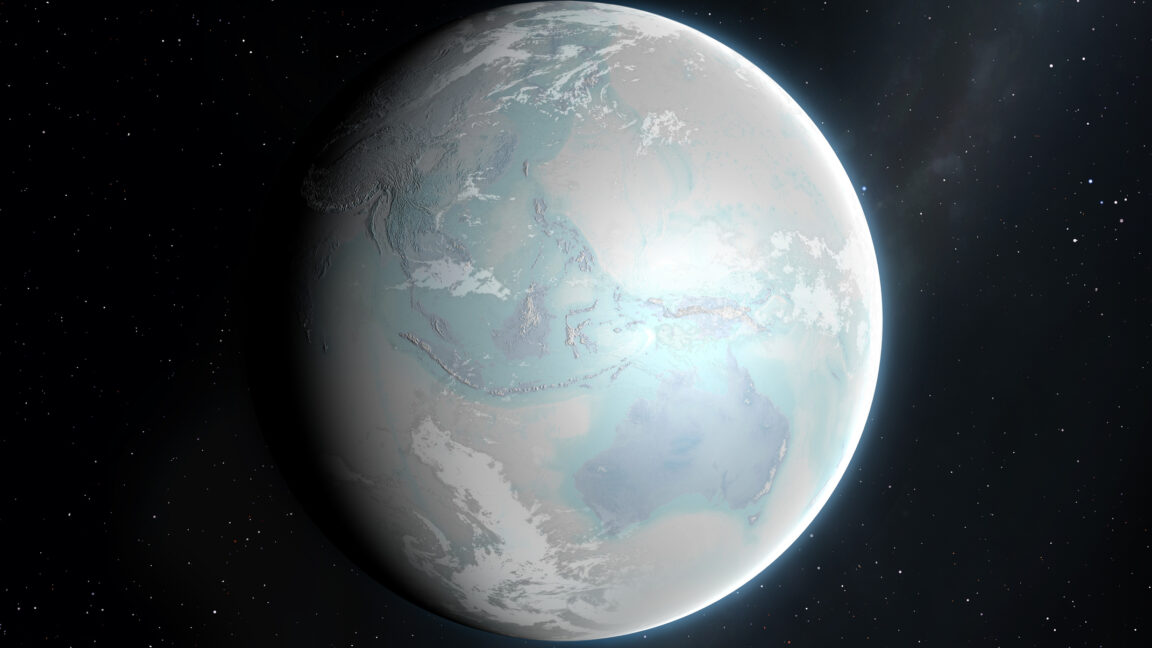

By now, it has been firmly established that the Earth went through a series of global glaciations around 600 million to 700 million years ago, shortly before complex animal life exploded in the Cambrian. Climate models have confirmed that, once enough of a dark ocean is covered by reflective ice, it sets off a cooling feedback that turns the entire planet into an icehouse. And we've found glacial material that was deposited off the coasts in the tropics.

We have an extremely incomplete picture of what these snowball periods looked like, and Antarctic terrain provides different models for what an icehouse continent might look like. But now, researchers have found deposits that they argue were formed beneath a massive ice sheet that was being melted from below by volcanic activity. And, although the deposits are currently in Colorado's Front Range, at the time they resided much closer to the equator.

In the icehouse

Glacial deposits can be difficult to identify in deep time. Massive sheets of ice will scour the terrain down to bare rock, leaving behind loosely consolidated bits of rubble that can easily be swept away after the ice is gone. We can spot when that rubble shows up in ocean deposits to confirm there were glaciers along the coast, but rubble can be difficult to find on land.

That has made studying the snowball Earth periods a challenge. We have the offshore deposits to confirm coastal ice, and we have climate models that say the continents should be covered in massive ice sheets, but we have very little direct evidence. Antarctica gives off mixed messages, too. While there are clearly massive ice sheets, there are also dry valleys, where there's barely any precipitation and there's so little moisture in the air that any ice that makes its way into the valleys sublimates away into water vapor.

Loading comments...

Loading comments...