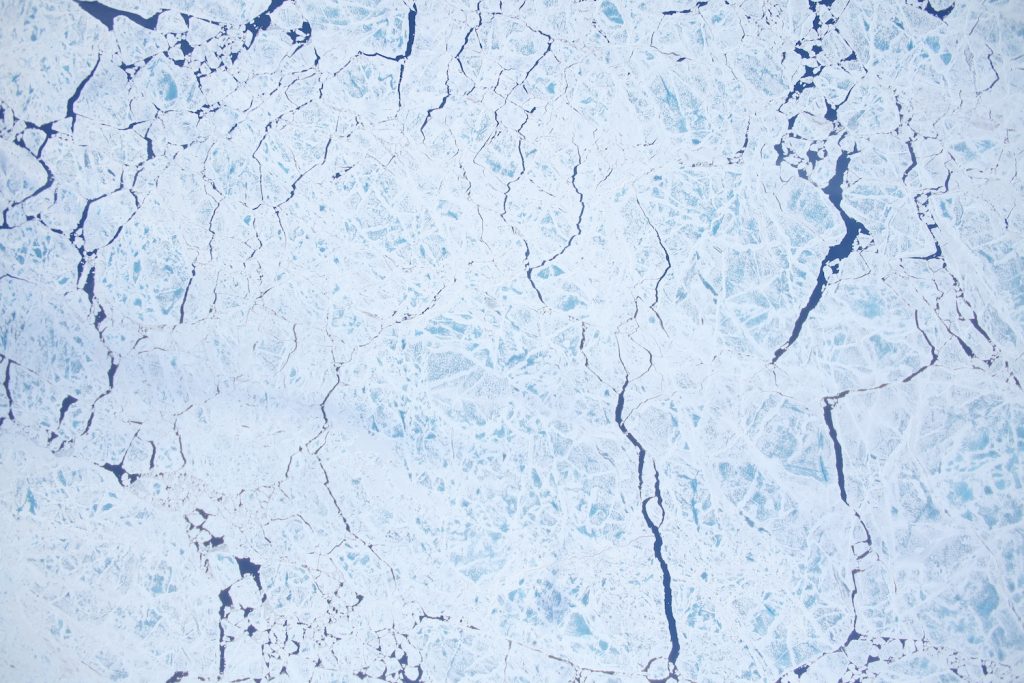

(Credit: NASA/Ramsayer)

by Kate Ramsayer / PITUFFIK, GREENLAND/

It was a duck that led me to treasure. And a plane that led me to the duck.

I set out that afternoon from Thule Air Base, walking down a gravel road with the Greenland Ice Sheet looming in the distance. I was trying to find an interesting view to film NASA’s Gulfstream V as it came back from a flight measuring sea ice for our ICESat-2 field campaign. I failed miserably, the plane landing as a spot in the distance far away.

Annoyed, I turned around and glanced at a pond of water by the road and spotted a duck – a fancy duck! I’m not a great birder, but I had studied up on the area birds and recognized it as a long-tailed duck. I crept closer to try to take a picture with my cell phone. It paddled away. I crept. It paddled. And then….

Treasure.

On the far side of the pond, a dull brown piece of fuzz blew in the wind, held by a clump of grass.

I gasped, forgot the duck, and ran over.

It was a dream come true for this knitter – qiviut, the undercoat of a musk ox, softer than cashmere, warmer than wool. I picked it up and rubbed it between my fingers – OK, I picked out a little dirt from it first, then rubbed it through my fingers – and had to laugh at how such a delicate and delicious fiber came from such a hulking beast.

Musk ox are found across the Arctic, and we had spotted several the weekend before on a drive out to the ice sheet. (What do sea ice scientists do on a day off of work? Visit an ice sheet, of course!) The first musk ox we saw was just over a mile from Thule Air Base, and I was surprised to see it so close to noisy humans, grazing peacefully in the hilly tundra of northwestern Greenland.

Although there isn’t a huge diversity of mammals in the region, they’ve been easy to spot on this campaign. That first trip beyond the base, we saw three musk oxen and several huge Arctic hares. I’ve started to recognize the Arctic foxes that live under the building I’m staying in, including a skittish brown kit and shaggy adults shedding their white winter fur.

(Credit: NASA/ Kate Ramsayer)

It’s possible the lack of trees makes wildlife-spotting easier. Lack of trees doesn’t mean a lack of flora, however. I was thrilled to realize that our summer campaign overlapped with wildflower season. Yellow poppy-like flowers, white puffballs of Arctic cottongrass, purple petals sticking up from a bed of moss, all thriving in the harsh environment. Walking to the ice sheet, one of the scientists and I fell behind while taking pictures of these hardy plants, growing in the rocky glacial moraine.

(Credit: NASA/Kate Ramsayer)

Back to the qiviut. I found that first bit, then looked around and saw more. Other clumps were hooked on a piece of wood, or a little flower. Musk ox hoofprints and poop provided further evidence of what had wandered by. I followed the prints and poop, picking up clumps of qiviut, like a kid on an Easter egg hunt. If you ever need to lure me into a haunted cottage in the woods, just leave a trail of heavenly fiber – I will skip merrily into the trap.

(Credit: NASA/Kate Ramsayer)

Walking back to Thule with a pocket stuffed with musk ox wool, admiring flowers poking up from the side of the road, watching a snow bunting flit across another pond, I know how fortunate I am to explore this unique environment. It’s like nothing I’ve seen before, and I doubt I’ll see anything like it again.

The Arctic is warming four times faster than any other region of the planet. I wonder how these hardy animals and plants, so well suited to their frozen ecosystem, will fare. A recent study described a population of polar bears in southwestern Greenland that now rely on glacial ice, instead of the sea ice that is typical seal-hunting grounds for other polar bears, as the sea ice in their habitat has disappeared for most of the year due to climate change.

As a writer who works with NASA scientists investigating how a warming climate impacts our planet, I’m continuously amazed at how well we can measure change even in these remote places. As a visitor to this incredible spot beyond the Arctic circle, I truly hope these flora and fauna can adapt to this ongoing change.