Some years ago, at the annual P.S. 3 book fair, I came across a Yiddish-English dictionary. This was a more serious Yiddish-English dictionary than the somewhat antic one I owned called “Dictionary Shmictionary!” That one includes a line drawing of a naked male, with body parts identified by their Yiddish words—one word for “head” and eight words for “penis.”

As I thumbed through the serious dictionary, the first word that caught my eye was mees—a word that even someone with only a smattering of Yiddish might be able to identify as the root word of meeskite, an ugly person. The Broadway musical “Cabaret” includes a song entitled “Meeskite.” When I was in college, someone I knew used to refer to a certain female he found unattractive as Mees America. (I wish I could report that I thought to reprimand him harshly for the misogyny reflected in that phrase, but those were different times.)

In the dictionary I was holding, the first definition for mees was indeed “ugly.” The second definition was “beautiful.”

I mentioned that unusual combination in “Family Man,” a memoir I published in 1998. In the intervening quarter century, I have often thought about how much I treasure a language that could define a word as both “ugly” and “beautiful”—and how much I regretted not knowing how to speak and understand it.

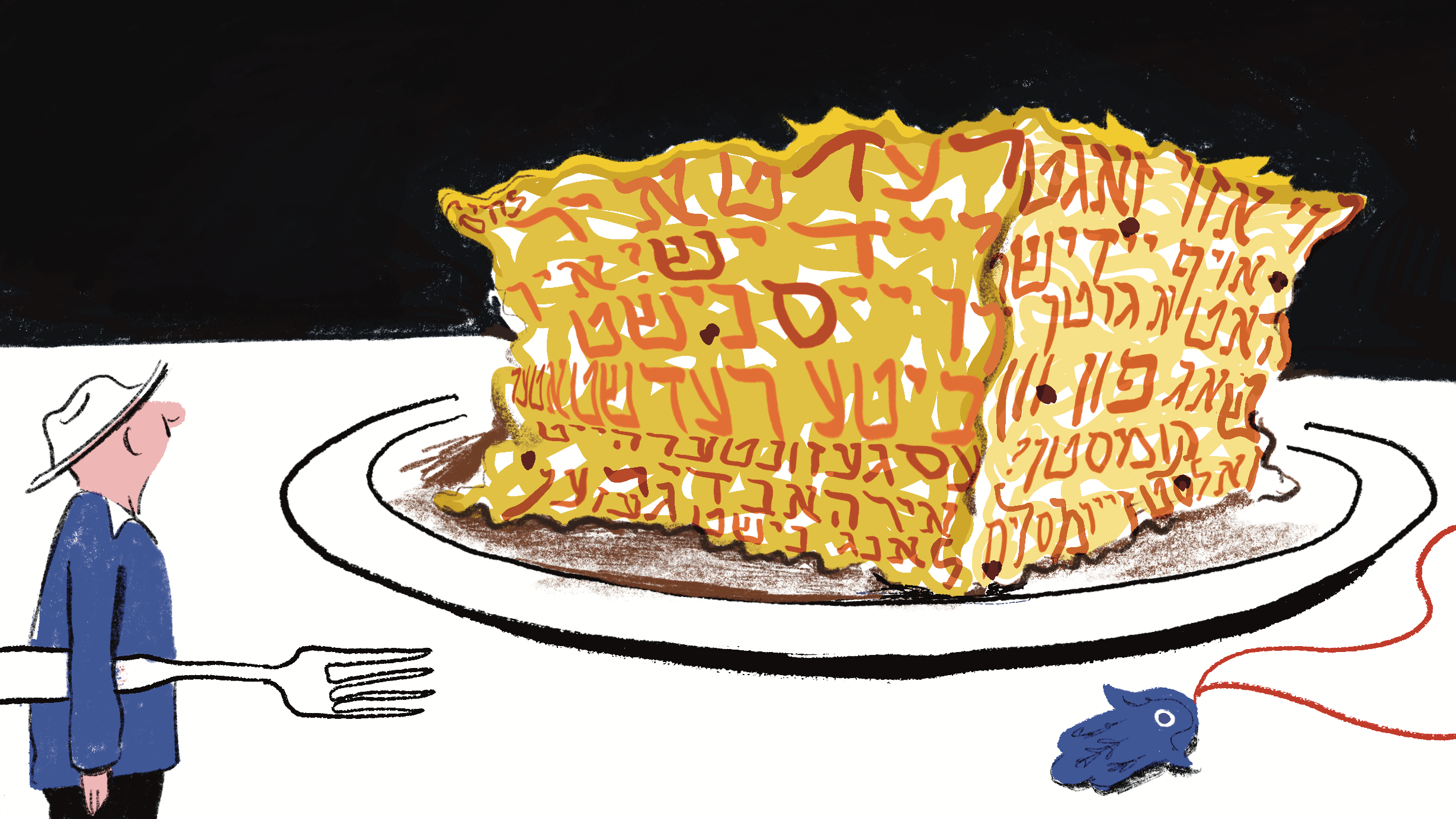

The reason for what might strike some as contradictory definitions was clear to me: fear of the Evil Eye. I could picture one of my great-aunts referring to an adorable toddler as a meeskite, because calling her beautiful might attract the malevolent attention of the Evil Eye the next time the toddler was in the kitchen and boiling water was on the stove.

My great-aunts were immigrants, but that doesn’t mean that I’d consider that picture foreign or old-fashioned. If asked today to provide a one-sentence distillation of my beliefs, in the way the Talmudic sage Hillel was challenged to explain the entirety of the Torah while standing on one foot, I would say that I believe in the First Amendment, and I fear the Evil Eye. Driving in rush hour, I’ve caught myself as I was about to comment on my surprise at encountering lighter than expected traffic; I knew that such a comment could cause the Evil Eye to produce a disabled eighteen-wheeler blocking all lanes around the next bend.

A smattering of Yiddish happens to be all the Yiddish I have—a condition common among people who grew up in homes where Yiddish was used when adults exchanged information that they didn’t want the children to overhear. I do know a number of Yiddish words. I know some Yiddish phrases and even a few homemade, half-Yiddish phrases (e.g., the phrase coined by the late Esther Kopkind, of New Haven, Connecticut, to describe something that’s not worth the trouble: quel schlep). I like to think that I could hold my own in a panel discussion on the distinctions among words like schmegegge and schmendrik and schlemiel—or the eight words for “penis,” for that matter. But I would have no idea of how to say, “Please pass the salt” or “Does anyone here speak English?”

I think that my sister knows more Yiddish than I do. When we were children, the explanation for that disparity was usually that, being a girl, she was naturally nosier than I was and thus would pay more attention when our mother was speaking on the phone to her mother or saying something to our father that they didn’t want us to understand. Nobody seemed to entertain the possibility that my sister simply had a better ear for languages than I did. But those were different times.

My language skills haven’t shown a lot of improvement. My French has never progressed much beyond what I absorbed from a high-school French class that seemed to consist mainly of cutting articles about France out of the Kansas City Star—a newspaper that was not known for a deep interest in international affairs. Over decades, my attempts to conquer the Spanish language have been repulsed. I assume that, should my demise result in some friendly publication (the local Wednesday shopper, for instance) deciding to publish an obituary, the headline would be “MONOLINGUAL REPORTER SUCCUMBS.”

My father, who was born in Ukraine, was brought to St. Joseph, Missouri, as an infant. He spoke English with the kind of accent that would be expected of someone whose home town is known for its historical connection to the Pony Express and Jesse James, but Yiddish must have been the first language of his home. In our home, he used it rarely, often for humorous effect. Some comedians of the Borscht Belt era were said to have believed that words beginning with the letter “K” are inherently funny. (They presumably made an exception for the Ku Klux Klan, which in its second incarnation had a fondness for K-words like “klavern,” for a local chapter, and “klonverse,” for a convention.) What those comedians thought about K-words was what my father thought about Litvaks—Jews with origins in what was once the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, an area that included not only present-day Lithuania but also Belarus and parts of nearby states like Latvia.

In “Family Man,” I acknowledged that I’d never thought to ask my father precisely why he found Litvaks risible. Having now done some not very strenuous research, I know that Litvaks were sometimes stereotyped by other Eastern European Jews as cold fish (the second definition in “Dictionary Shmictionary!” defines the word “litvak” as “a clever but insensitive person”—presumably no matter where in the Pale of Settlement he comes from). Litvaks seasoned their dishes differently than Jews from places like Ukraine. They pronounced any number of words differently. One of the first jokes I ever heard as a child was based on the different ways of pronouncing a pudding made with noodles or potatoes: Some people say “kugel” and some people say “keegel,” but my aunt is Americanized; she says “pudgink.” (When it came to that particular schism, our house was strictly “kugel” territory.) In Yiddish, Litvaks had an accent that was once described to me as sounding like someone trying to speak Yiddish the way a BBC announcer who’s covering the monarchy speaks English.

But I never heard any of that from my father. To him, the very word “litvak” was funny. Looking back on it, I think that in my father’s view the old joke-starter “two guys walk into a bar” could be made at least faintly humorous on its own by saying “two Litvaks walk into a bar.” He was not alone in that belief. In “Son of a Smaller Hero,” an early novel by Mordecai Richler, the master chronicler of Montreal Jews, some Jewish pranksters come across a beach that displays a sign that says “THIS BEACH IS RESTRICTED TO GENTILES,” and sneak back at night to change the sign to “THIS BEACH IS RESTRICTED TO LITVAKS.”

The one Litvak we had close at hand was my maternal grandmother, who was born in what was always referred to in my family as “near Vilna.” She was not my favorite relative, and I started saying so long before I had an opportunity to mention her in print. More than once, I complained to my mother about my grandmother referring to our dog, Spike, as “the hundt.” My mother would tell me that hundt was simply the Yiddish word for dog, and I would reply, “Not the way she said it.”

I thought about that many years later when, during a New York mayoral election campaign, the comedian Jackie Mason, a supporter of Rudy Giuliani, was criticized for referring to David Dinkins as “a fancy schvartze with a mustache.” Mason’s defenders said that the offending word simply means black in Yiddish. Not the way he said it.

In the early sixties, I spent a year in the South covering the civil-rights struggle, and I once saw Ku Klux Klansmen in their full regalia. They were picketing in support of a department store in Atlanta that had resisted the desegregation of department-store lunch counters. All but one of the Klansmen wore white robes. One was in green, and he seemed to be in charge. I asked him what sort of Klan office-holder he was.

“I’m a Kleagle,” he answered.

“You mean a Klugel,” I said reflexively.

The man in the green robe looked puzzled, apparently having had limited experience with Eastern European Jewish puddings. I changed the subject.

Eventually, I had reason to be puzzled myself. “Kugel” was indeed the only way the dish was pronounced in my family, but a startling fact had finally dawned on me: “kugel” is the Litvak pronunciation. I should have made the connection years ago. I have long been aware that among South African Jews, who, famously, are virtually all Litvaks, “kugel” is so firmly embedded in Yiddish that it even has a slang meaning. A hyper-materialistic and overdressed Jewish woman is called (though not by me, still smarting from memories of the Mees America episode) a kugel.

According to the YIVO Encyclopedia of Jews in Eastern Europe, “kugel” was also the pronunciation generally taught in schools even in non-Litvak areas of the Pale of Settlement. But surely not in the schools of St. Joe, Missouri. Did my father use it ironically? Did my grandmother somehow have control in our house of how to pronounce certain traditional Jewish dishes? Were there other words that I grew up pronouncing as a Litvak would? Did that mean that if I ever did learn conversational Yiddish I might be taken for a Litvak?

“But if your grandmother was a Litvak,” a friend said to me, “then you are partly Litvak yourself.”

“You know,” I replied, “I honestly never thought of that.”

Even if it made me sound like a Litvak, I’d take great pleasure in knowing more than a smattering of Yiddish. Leafing through “Dictionary Shmictionary!” recently, I realized that I might already know enough Yiddish words to cobble together a short sentence or two, assuming a verb was not an absolute requirement. I could imagine myself in the future casually saying to a dinner companion, in impeccable Yiddish that retains only a trace of a Kansas City accent, “Please pass the salt.”

May the Evil Eye be too busy with nefarious schemes elsewhere to have heard that. ♦