/ɡʁavitaˈt͡si̯oːn/ (German, noun, feminine: gravity)

Ernst, S.M., and contributors, 2019. gravitation - n-body-simulation performance test suite. https://github.com/pleiszenburg/gravitation

gravitation is a collection of experiments on writing, benchmarking and optimizing n-body simulations, taking the "two language problem" to the extreme.

In science and engineering, it is a prominent scenario to use Python as a high level or "glue" language on top of code written C, Fortran or other "fast" languages. In some cases, a Python project starts out as a Python wrapper around other, possibly older non-Python code. In other cases, functionality is rapidly prototyped in Python. Eventually, performance-critical code-paths are identified, isolated and optimized - or even re-implemented in a second, "faster" language. Either way, there is a great diversity of possible approaches and tools for accelerating Python code and/or combining it with other languages. Depending on a project's requirements, it can be hard to choose the right one(s). Virtually all are based on at least one more programming language other than Python, in one way or the other - hence the "two language problem". gravitation aims to demonstrate a broad selection of approaches and tools. Both their performance and level of implementation complexity are (cautiously) compared based on a (single) typical computation-bound problem: n-body simulations. n-body simulations scale up easily, which in return gives invaluable insights into the scaling behaviors of all demonstrated approaches. They are also fairly trivial targets for parallelization, allowing to study their behaviors on hardware platforms with multiple CPU cores (both heterogeneous and homogeneous), multiple CPU sockets and GPUs or comparable numerical accelerators.

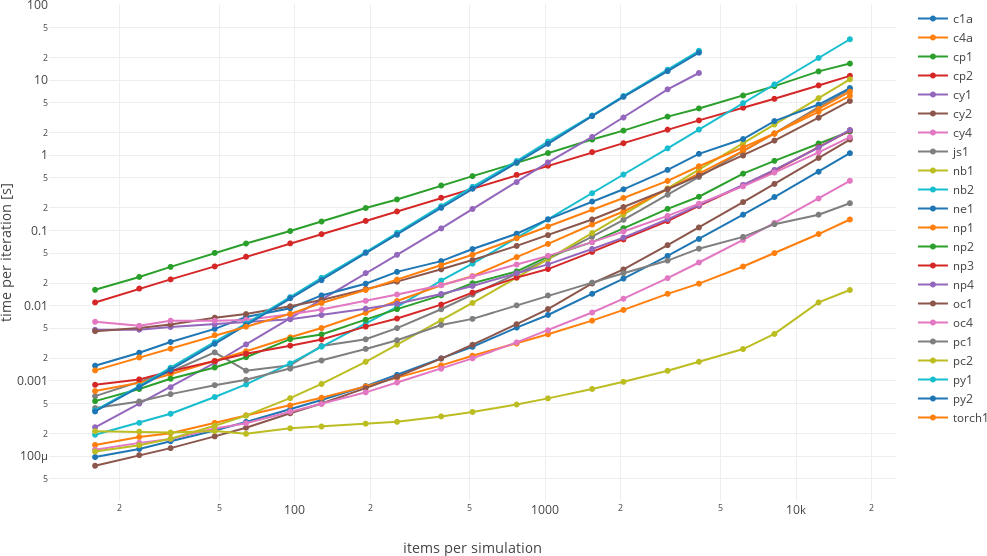

screenshot of interactive benchmark plot - click on the image to see interactive version

The plot above was generated running the commands below on an Intel i5-4570 CPU with a Nvidia GeForce GTX 1050 Ti graphics card. CPython 3.6.7, GCC 8.2.0, Linux 4.15.0 x86_64, Octave 4.2.2, CUDA Toolkit 9.1, Nvidia driver 390.77. CPython, GCC and Linux Kernel are original distribution binaries of Linux Mint 19.1.

# Faster kernels, can work on larger numbers of bodies

gravitation benchmark -p 4 -i 3 -t 5 -k c1a -k c4a -k cp1 -k cp2 -k cy2 -k cy4 -k js1 -k nb1 -k nb2 -k np1 -k np2 -k np3 -k np4 -k oc1 -k oc4 -k pc1 -k pc2 -k torch1 -k ne1 -b 4 14 -l benchmark_long.log

# Slower kernels, should work on smaller numbers of bodies

gravitation benchmark -p 4 -i 3 -t 5 -k py1 -k py2 -k cy1 -b 4 12 -l benchmark_short.log

# Transform logs

gravitation analyze -l benchmark_long.log -o benchmark_long.json

gravitation analyze -l benchmark_short.log -o benchmark_short.json

# Plot data and display in browser

gravitation plot -l benchmark_long.json -l benchmark_short.json -o benchmark.htmlThe design idea is simple: A number of n-body simulation implementations, referred to as kernels, are derived from a single base class (universe_base) written in pure Python. It provides the fundamental Python infrastructure while it can not (and should not) perform a simulation on its own.

gravitation kernels divide each simulation time step into two major stages, updating certain parameters of all bodies:

- Acceleration (i.e. the forces between all pairs of bodies), O(N^2)

- Velocity and position, O(N)

Because of its O(N^2) complexity, stage 1 is the prime target for optimizations and/or re-implementations. Therefore, the base class offers a default implementation for stage 2 only. A kernel [class] derived from the base class must (at least) implement stage 1 on its own. Overloading stage 2 is possible but not required. The "py1" kernel serves as a minimal working reference kernel, implementing stage 1 in pure Python without dependencies.

Kernels must not change the "interface for frond-end code" exposed by the base class. "Python users" or other pieces of Python software must be able to run all kernels transparently without knowing about any of the intricate details of their implementations. Both position and velocity data of every body (also referred to as "point mass") must be accessible after every time step through iterable objects (e.g. Python lists, arrays or numpy arrays). For reference, have a look at the class _point_mass. Kernels must be located in src/gravitation/kernel for being auto-detected.

Certain kernels allow to switch between single precision floating point numbers and double precision floating point numbers, others do not (due to language- or instruction-level restrictions for instance). The infrastructure in question is prepared but not perfect yet and will be improved in future releases. In the meantime, single precision is used by default where possible.

While kernels compute time steps, Python's garbage collector remains switched off. This allows clean results not affected by "randomly occurring" garbage collections. Directly before and after every time step, a garbage collection is triggered "manually". The time required for collecting garbage after a time step has been computed is also (separately) measured and recorded.

All of gravitation's kernels reside in the kernel sub-module.

- py*: Pure Python, single-thread (compatible with pypy)

- np*: Both single-thread and parallel, based on numpy

- cp*: numpy-compatible implementations using cupy (GPU/CUDA)

- torch*: almost numpy-compatible implementations using torch (GPU/CUDA)

- nb*: accelerated by numba, both CPU and GPU (CUDA), single-thread

- ne*: accelerated by numexpr, single-thread

- pc*: PyCUDA kernels

- cN*: C backends, both single-thread and parallel, both plain C and SIMD (SSE2) intrinsics

- cy*: Cython backends, both plain Python (compiled) and isolated Cython, both single-thread and parallel

- js*: JavaScript backends, currently single-thread and based on py_mini_racer (V8)

- oc*: Octave backends, very likely Matlab-compatible (not yet tested), based on oct2py, both single-thread and parallel

Contributions are highly welcome:

- Faster (pure) Python implementation(s) - "pure" as in "standard-library only"

- Faster (pure) numpy implementation(s)

- Balanced / optimized combinations of numpy, numba and numexpr (for individually both, smaller and larger numbers of bodies)

- Rust backend(s)

- Go backend(s)

- Swift backend(s) - if this is at all possible

- C backend(s) with AVX(2) and AVX512

- C backend(s) with CUDA (without PyCUDA)

- C backend(s) called through cffi (instead of ctypes)

- C++ backend(s) called through different interfaces

- Faster CUDA backend(s) in general, with or without PyCUDA

- openCL backend(s), any language

- ROCr/ROCm backend(s), any language

- Fortran backend(s)

- Julia backend(s)

- TensorFlow backend(s), for both CPU and GPU - (theoretically) possible

- JavaScript on nodejs

- Faster JavaScript in general

- Parallel JavaScript with workers

- Matlab on original Matlab interpreter (not Octave)

- Lisp backend(s)

- Parallel backend(s) based on MPI (in any language)

- Parallel backend(s) based on Dask (in any language)

Does actual physics matter? No. gravitation is certainly not about physics.

Does numerical accuracy matter? Yes and no. In certain applications, numerical accuracy is more desirable than speed. In other cases, it is the opposite or somewhere in between. Studying the impact of various trade-offs with respect to both speed and accuracy is therefore highly interesting.

What about "optimizations" such as e.g. tree methods, for instance Barnes–Hut? This is not what gravitation is about. gravitation is intentionally written as a direct n-body simulation where forces are computed for all pairs of bodies (in time steps of equal length).

Why is JavaScript even on this list? At first, it seemed like a crazy experiment. But after some initial tests with V8 and Mozilla's latest monkey, it became obvious that JavaScript engines had come a long way. The results were simply impressive. Why should one use it? Well, the basic argument is that JavaScript currently is the most widely used programming language in existence, for better or for worse. JavaScript development skills are therefore relatively easy to get hold of. There are even books about how to use it for research projects including numerical computations, e.g. "JavaScript versus Data Science" aka. "JavaScript for Scientists and Engineers".

Why is cffi desired if there is already a kernel using ctypes? From a functional point of view, cffi and ctypes do not differ much. However, they differ in both code complexity and performance. The differences when scaling up are highly interesting.

What about different compilers and compiler versions? This is yet another interesting dimension that is intended to be added to the benchmark infrastructure. The project's C code already shows significant differences in performance if compiled with GCC 4 or 6 or clang/LLVM.

Why are the numpy implementations so (relatively) slow? Good question - no idea. Insights and better implementations are highly welcome. Current implementations focus on reducing or even eliminating memory allocations.

What about Intel Compilers, MKL and MKL-enabled numpy? As far as testing went, there is no significant difference between "regular" and MKL-enabled numpy. gravitation is about plain number crunching and does not use any type of "higher" algebra that has been optimized in MKL. The Intel C compiler on its own does seem to make a difference, however.

Are contributions limited to what is listed under "Desired / Planned Kernels"? No, not at all. Anything that works and adds a new facet to this project is truly welcome.

What about scaling up on computer clusters / super computers? Although this has yet not been within the scope of this project, contributions are nevertheless welcome.

gravitation was developed for and tested on x86_64 Linux. However, there is no reason why it should not work on other operating systems (Windows, Mac OS, BSD, Solaris, etc.) or other platforms (ARM, Power, etc.). The basic benchmark infrastructure should be platform independent. Certain kernels might require a few tweaks (e.g. alternatives to using /dev/shm for "on-disk" caching or inter-process communication via files). Kernels depending on certain x86-specific features will of cause not work on other platforms. A CUDA-compatible accelerator is highly recommended, although without it only kernels depending on CUDA will not work. Other kernels are not affected. There are no pre-compiled binaries at this point (although this may change in future). Installation is supported through pip. Support for conda is likely going to be added.

- Linux (x86_64)

- CUDA Toolkit

- C-compiler: GCC or Clang/LLVM (consult your Linux distribution's documentation for details)

- openMP headers (consult your Linux distribution's as well as your compiler's documentation for details)

- gnuplot

- Octave

- CPython 3.6 or later - likely part of your Linux distribution (consult its documentation for details)

- PyCUDA

- PyTorch

- CuPy

Installing all of the above into a virtual environment is highly recommended.

You can install the latest version of gravitation with pip directly from GitHub:

pip install -vU git+https://github.com/pleiszenburg/gravitation.git@masterYou may also clone this repository and install gravitation in development mode:

git clone [email protected]:pleiszenburg/gravitation.git

cd gravitation

pip install -v -e .A typical gravitation workflow is command-line oriented. However, it is also possible to import gravitation from other Python scripts - see chapter on APIs for details.

Test an individual kernel with gravitation realtimeview. It visualizes a simulation in "real-time", i.e. as fast as time steps are computed.

Run a benchmark across multiple kernels with gravitation benchmark. It will run gravitation worker for all possible permutations of its given input parameters. Its results will be stored into a log file.

Transform the log file into a well structured JSON file with gravitation analyze for further analysis with your favorite tools.

Plot one or more JSON files with gravitation plot for quick exploration.

Available kernels and the maximum number of available threads will be auto-detected.

The default scenario for benchmarks is "galaxy" (a single, galaxy-like constellation of "stars" with a central "heavy body" loosely resembling a back hole). If you call the benchmark worker script gravitation worker directly e.g. for testing alternative Python interpreters, the number of bodies in a galaxy can be tuned as follows: --scenario galaxy --scenario_param '{"stars_len": 2000}' ("scenario_param" expects a JSON string). Alternatively to gravitation worker, you can also start a worker with python -c "from gravitation.cli import cli; cli()" worker.

(env) user@box:~> gravitation --help

Usage: gravitation [OPTIONS] COMMAND [ARGS]...

gravitation, the n-body-simulation performance test suite

Options:

--help Show this message and exit.

Commands:

analyze analyze benchmark logfile

benchmark run a benchmark across kernels

plot plot benchmark json data file

realtimeview view a simulation progressing in realtime

worker isolated single-kernel benchmark worker

(env) user@box:~> gravitation benchmark --help

Usage: gravitation benchmark [OPTIONS]

run a benchmark across kernels

Options:

-l, --logfile TEXT name of output log file [default:

benchmark.log]

-o, --data_out_file TEXT name of output data file [default: data.h5]

-i, --interpreter TEXT python interpreter command [default:

python3]

-k, --kernel [c1a|c4a|c4b|cp1|cp2|cy1|cy2|cy4|js1|nb1|nb2|ne1|np1|np2|np2b|np2c|np3|np4|oc1|oc4|pc1|pc2|pc3|py1|py2|torch1]

name of kernel module, can be specified

multiple times

-a, --all_kernels run all kernels [default: False]

-b, --n_body_power_boundaries <INTEGER INTEGER>...

2^x bodies in simulation, for x from lower

to upper boundary [default: 2, 16]

-s, --save_after_iteration INTEGER

save model universe into file iteration x,

-1 if nothing should be saved

-i, --min_iterations INTEGER minimum number of simulation steps

[default: 10]

-t, --min_total_runtime INTEGER

minimal total runtime of (all) steps, in

seconds [default: 10]

-d, --display [plot|log|none] what to show during benchmark [default:

plot]

-p, --threads [1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8]

number of threads/processes for parallel

implementations, can be specified multiple

times, defaults to maximum number of

available threads

--help Show this message and exit.

(env) user@box:~> gravitation analyze --help

Usage: gravitation analyze [OPTIONS]

analyze benchmark logfile

Options:

-l, --logfile FILENAME name of input log file [default: benchmark.log]

-o, --data FILENAME name of output data file [default: benchmark.json]

--help Show this message and exit.

(env) user@box:~> gravitation worker --help

Usage: gravitation worker [OPTIONS]

isolated single-kernel benchmark worker

Options:

-k, --kernel [c1a|c4a|c4b|cp1|cp2|cy1|cy2|cy4|js1|nb1|nb2|ne1|np1|np2|np2b|np2c|np3|np4|oc1|oc4|pc1|pc2|pc3|py1|py2|torch1]

name of kernel module [required]

--scenario TEXT what to simulate [default: galaxy]

--scenario_param TEXT JSON string with scenario parameters

[default: {}]

-o, --data_out_file TEXT name of output data file [default: data.h5]

-s, --save_after_iteration INTEGER

save model universe into file iteration x,

-1 if nothing should be saved

-i, --min_iterations INTEGER minimum number of simulation steps

[default: 10]

-t, --min_total_runtime INTEGER

minimal total runtime of (all) steps, in

seconds [default: 10]

-p, --threads [1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8]

number of threads/processes for parallel

implementations [default: 1]

--help Show this message and exit.

(env) user@box:~> gravitation plot --help

Usage: gravitation plot [OPTIONS]

plot benchmark json data file

Options:

-l, --logfile FILENAME name of input log file, can be specified multiple

times [default: benchmark.json; required]

-o, --html_out FILE name of output html file [default: benchmark.html;

required]

--help Show this message and exit.

(env) user@box:~> gravitation realtimeview --help

Usage: gravitation realtimeview [OPTIONS]

view a simulation progressing in realtime

Options:

-k, --kernel [c1a|c4a|c4b|cp1|cp2|cy1|cy2|cy4|js1|nb1|nb2|ne1|np1|np2|np2b|np2c|np3|np4|oc1|oc4|pc1|pc2|pc3|py1|py2|torch1]

name of kernel module [required]

--scenario TEXT what to simulate [default: galaxy]

--scenario_param TEXT JSON string with scenario parameters

[default: {}]

--steps_per_frame INTEGER simulation steps per frame, use scenario

default if -1 [default: -1]

--max_iterations INTEGER maximum number of simulation steps, no

maximum if -1 [default: -1]

--backend [pygame] plot backend [default: pygame]

-p, --threads [1|2|3|4|5|6|7|8]

number of threads/processes for parallel

implementations [default: 1]

--help Show this message and exit.

gravitation exposes all available kernels through a dictionary-like object, inventory. Initially, inventory only provides a "list" of available kernels. Kernel meta data must be loaded manually (load_meta). The kernel's Python (sub-) module also must be imported manually (load_module). Meta data is loaded without importing the kernel.

Kernels have to be "started" before they can perform any type of computation (start). Once they are started, they can compute as many time steps as desired (step). If a kernel object is supposed to be discarded, it can be "stopped" (stop). A stopped kernel can not be used for computations. Bodies / point masses must be added to a kernel (add_object) before it is started.

from gravitation.lib.load import inventory

inventory[kernel_name].load_meta() # loads meta data from kernel source

fields = inventory[kernel_name].keys() # provides access to kernel meta data field names

field_data = inventory[kernel_name][field_name] # provides access to kernel meta data

inventory[kernel_name].load_module() # attempts to import kernel module

kernel_cls = inventory[kernel_name].get_class() # returns kernel's universe class

kernel_obj = inventory[kernel_name](*args, **kwargs) # returns instance of kernel's universe class

kernel_obj.add_object(**kwargs) # adds body / point mass to universe

kernel_obj.start() # runs initialization routine(s) for kernel prior computations

kernel_obj.step() # computes one time step

kernel_obj.stop() # runs clean-up routine(s) after a kernel has been usedFor simplification of certain workflows, the simulation (sub-) module provides a number of convenience routines.

from gravitation.lib.simulation import (

create_simulation,

create_solarsystem,

create_galaxy,

load_simulation,

store_simulation,

)