The final project for CSE 5559 by team VisAiR with members Skylar Wurster ([email protected]), Logan Frank ([email protected]), and Njoki Mwagni.

With the recent improvements in generative adversarial networks (GANs), many networks have come about that allow for generation of realistic images. They do this using a generator-discriminator pair. The generator's goal is to generate convincing looking images that will "fool" the discriminator, and the discriminator is learning real from fake images. Some create cars, some create human faces, and some create cats! Here are some examples:

A generated cat from a sketch and face generated from noise.

Some GANs are specifically trained to generate an output image from an input sketch or segmentation map. A segmentation map is simply an image where each pixel color corresponds to a specific class, like "grass", or "sky" or "table". Here is an example of a segmentation map, and the corresponding actual photo:

A segmentation map for a corresponding image. Notice how the segmentation map is hard to see, because it is single channel, meaning every class is a shade of gray!

Some fun tools online allow you to draw sketches and see the output, without having to run the network on your own machine!

The web-based interface for GAUGAN, NVidia's award winning GAN presented in SIGGRAPH 2019

Another GAN that won a few awards at SIGGRAPH 2019 is called GAUGAN, which was trained on an unreleased Flickr landscapes dataset. We find this one particularly interesting because it is lightweight and allows us to see changes to the output image (after drawing) reasonably quickly on new hardware. You can find the interactive demo here.

Recently, image-captioning has also been an important topic for research. Automatic image-captioning is an Artificial Intelligence (AI) task that exists in the visiolinguistic research space between Computer Vision (CV) and Natural Language Processing (NLP). Captioning an image requires understanding the image and understanding language. Understanding the image by itself requires recognizing the scene, detecting objects with the scene and their relationships to or interactions with other objects. Once the image is understood, the system must follow linguistic rules of syntax and semantics in order to generate a well-formed sentence that describes the image.

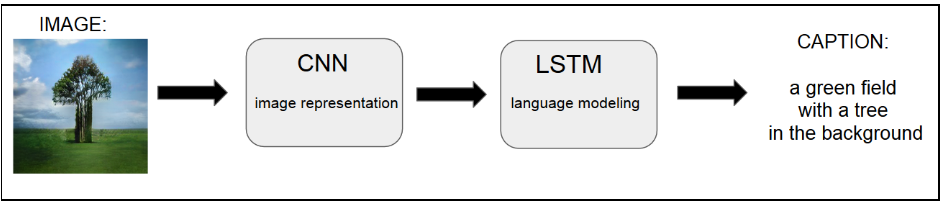

Some current image-captioning systems employ an encoder-decoder paradigm. A CNN-encoder extracts features from the input image and an RNN-decoder generates a caption from the extracted features. The features are learned automatically by training neural networks on image-description and image-captioning datasets like Visual and Linguistic Treebank, Flickr8k/30k, MS COCO and Abstract Scenes datasets.

With these two new advances - in GANs and automatic image captioning - we were curious: what changes in our input to a generative image network would create large changes in our output image and caption? Would small changes vastly affect the output image? Or would it affect the caption more than the image? To test these questions, we use NVidia's GAUGAN (based on Pix2pix with a new SPADE normalization/denormalization layer) for the generator network and ResNet-152 for the captioning network. We create an interactive browser based HTML page to draw the segmentation map and view outputs, a Python+PyTorch backend to run all of our models, and use flask to tie the front and backend together.

The proposed pipeline: Sketch a segmentation map, see it as a real picture, then look at the caption

To allow the users to see how much their changes have an impact on the output, we will also show metrics between any two previous images, such as MSE, SSIM, and feature distance, measured by a feature extracting network.

Our generator network must be created first, so that our captioning network can get inputs, and so our front end knows which classes its allowed to draw on the segmentation map. As mentioned, we use GAUGAN from NVidia. They offer 3 pretrained models on different datasets, but we specifically use ade20k because of its high class count - 150. This should get users plenty of options for creating indoor and outdoor scenes, with classes ranging from “sky” and “earth” to “table” and “window” and “person”. The network that won NVidia a few awards at SIGGRAPH 2019 isn’t released unfortunately, but feel free to create and train a network on the Flickr-landscapes dataset they used. In my opinion, the resulting landscapes look much better then the ones created by the network pretrained on ade20k, but ade20k allows us to generate more types of scenes.

The image-captioning task consists of two sub-problems, image classification and sequence modelling, which are addressed using existing solutions to each sub-problem, a convolution neural network(CNN) and a recurrent neural network (LSTM) respectively. The CNN creates a feature vector representation of the image and the feature vector is used as input to the LSTM, which generates the caption.

Image captioning using encoder-decoder architecture

The pre-trained CNN is a ResNet-152 model trained on the ImageNet Large Scale Visual Recognition Challenge 2012 (ILSVRC2012) image classification dataset.

The LSTM decoder is a language model conditioned on the feature vector from the CNN. During training, captions are turned into variables that the model learns to predict, e.g., if the caption is “a green field with a tree in the background,’ the source and target sequences are:

- Source: [, a, green, field, with, a, tree, in, the, background ]

- Target: [a, green, field, with, a, tree, in, the, background, ]

The LSTM model is trained to predict each word in the target sequence from the feature vector and the preceding words in the source sequence. During testing, the preceding generated word is fed back to the LSTM as the next input.

As noted, we use HTML/js, specifically relying on the html attribute. This has a plethora of built in functionality, especially with getContext(“2D”), which allows us to do simple 2D drawing operations on the canvas pixels with efficiency. Utilizing this, we allow the user to draw using two shapes, a square or a circle, with a size specified by a slider.

Colors are selected to the left of the drawing area, where each class is highlighted with its segmentation map color. This isn’t its REAL segmentation map color. Its real one is actually just a number between 0-150. But then we’d be drawing in grayscale! So instead, we devise a color mapping function that sends N -> N^3 such that the mapping is a bijection within our domain of interest by using a bit-shifting technique:

def get_cmap(N):

'''

Creates an arbitrary color map for some number of classes (N) using bit shifting

'''

cmap = np.zeros((N, 3), dtype=np.uint8)

for i in range(N):

r, g, b = 0, 0, 0

id = i + 1 # let's give 0 a color

for j in range(7):

str_id = uint82bin(id)

r = r ^ (np.uint8(str_id[-1]) << (7 - j))

g = g ^ (np.uint8(str_id[-2]) << (7 - j))

b = b ^ (np.uint8(str_id[-3]) << (7 - j))

id = id >> 3

cmap[i, 0] = r

cmap[i, 1] = g

cmap[i, 2] = b

#print(str(i+1)+","+str(cmap[i,0])+","+str(cmap[i,1])+","+str(cmap[i,2]))

return cmap

This way, we’re drawing with visually appealing colors instead of indistinguishable shades of gray.

Segmentation classes can be selected on the left in the scrollpane and drawn in the canvas

We encountered smoothing/anti-aliasing issues using the standard line drawing functionality, because colors would get blended. Suppose we had some pretrained model that had just two classes, and we gave class 1 a segmentation map color of red (255,0,0) and class 2 a segmentation map color of blue (0,0,255). As it turns out, the line drawing functionality attempts to smooth the corners of drawn lines, so if I draw class 2 on top of class 1, there might be pixels that are (127,0,127), which doesn’t exist in our mapping. For that reason, we couldn’t use that functionality and had to write our own line drawing, which just interpolates 10 points on the line between the last cursor location and the current one, and draws the shape at each point without smoothing.

Due to the lightweight nature of our models, we were able to run our GUI in real-time, to an extent. Whenever the user lets go of the mouse button, the output image and caption are updated within a quarter second. We experimented with true real-time generation, but it became unclear how the undo/redo functionality would work with that addition.

A full demo showing the realtime updates of the image and metrics on the browser

The GUI also hosts 3 graphs as well as a full history of generated images. The current metrics shown will always be between the last two images generated, unless the user selected a different image. You can tell which images are selected by examining which ones are highlighted in yellow. A different image can be selected by clicking one from the list. This will update the reported metrics as the distance between the two selected images. The graphs below show the sequence of the last 20 selections. By default, this will show the metrics changing over time as you make additions. You can hover over a single data point on any graph to see which two images created that metric, and then you can select those to be shown by clicking on them in the image history panel.

A closer look at the metrics section. We are able to select any previously created image in the scrollpane on the left. Selected items are highlighted

Images and captions generated for an outdoor scene with a road, bus, and traffic light, at each point in the process

With our working project, we went to test out our questions posed in the beginning. How well does an image captioning network caption generated images? Do small changes in our input segmentation map create large changes in the output image or caption?

Let’s walk through the image above: the caption for image 1b, above, fails to correctly identify objects, though its estimation isn’t far from what you might see (sans the kite); the caption for 2b misidentifies the location, and the caption for 3b identifies the location and the bus, but not the traffic light. The improvement of captions with the population of objects is also apparent in indoor scenes.

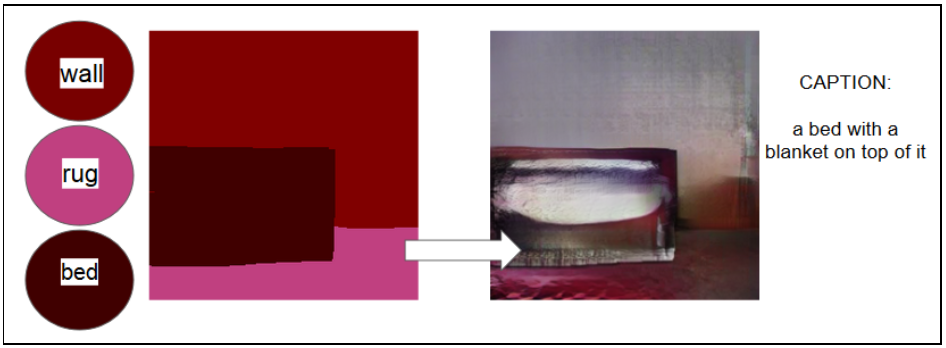

The segmentation map and corresponding generated image

The image above was captioned as “a bed with a blanket on top of it.” The drawing was constructed in the following order: (1) wall, (2) rug, (3) bed, and the generated mid-drawing images were captioned as the following:

- a man is playing tennis on a tennis court;

- a large window with a glass vase on it.

- a bed with a blanket on top of it

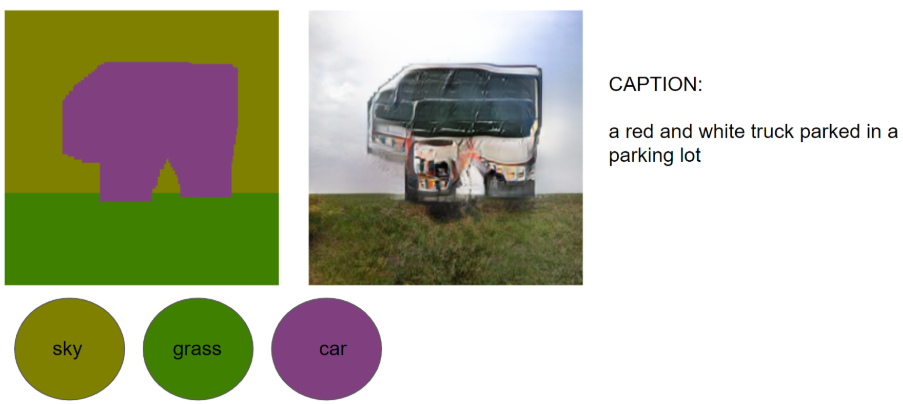

An example of how drawing location can affect the outcome caption and image

One might also wonder how the location of objects changes the caption or output. Above, we have two very similar segmentation maps. The mustard color is sky, the green color is grass, and the purple color is trees. We place trees in the background above, and trees in the foreground below.

Taking a look at the generated images, we can see a few key differences:

- The sky color changed considerably, from blue on top to white below

- The image below seemed to create 6 trees, 3 in the background and 3 in the foreground

- The horizon line is slightly different, with the above image being more clear and the below image almost looking slanted and different where the trees come to the ground.

With these noted, we are surprised to see that the bottom image was captioned “A group of cows grazing on a lush green field”. We don’t see that at all! It is unclear what the image captioning network saw that would lead it to believe there are cows in the image. The above image was captioned very well. This seems to say that location of the segmentation map pixels does have a considerable change in both the output photo and the caption.

Because of ade20k’s large number of classes, we thought it would be interesting to see what would happen if we put a class in an area where it typically wouldn’t belong, such as a “door” in the middle of the “sky”.

Image and caption generated for an inordinary scene of a truck on grass

In the example above, we put a car in a field. The output image isn’t anything convincing; a human might be able to recognize that as a truck/car looking object in a field. But interestingly, the image captioning network was so sure of the truck, that it thought it must have been in a parking lot, since obviously trucks can’t be on grass! This may be due to a lack of abstraction by the captioning network. Natural images taken from everyday scenes wouldn’t have this kind of relationship unless the dataset was constructed purposefully to make this issue less of a problem. This may point to an interesting usefulness for this GAN. If an algorithm could be used to caption segmentation maps, then we could use the GAN to generate real images from that segmentation map, and then add that new <image, caption> pair to the training data for the original image captioning network. This way, we could create scenes that aren’t “natural”, strictly speaking.

We believe there are many ways this project could be improved to give even more useful information to users (or to make it more fun!) First and foremost, using additional datasets and pretrained models for this SPADE based GAN would be a good step. We’ve only looked at ade20k, which might have specific traits due to the large number of classes. NVidia’s GAUGAN was trained on Flickr-landscapes, which had much less classes. We hypothesize that due to the low number of classes, generated images were more realistic to humans. The addition of other pretrained models wouldn’t be that difficult to implement.

We also believe different GAN models would be interesting to compare within the app on the same dataset. For instance, you might draw one segmentation map and observe the outputs generated by 2 different GANs trained on the same dataset. This would be helpful for user studies deciding which GAN creates more realistic images. Implementing this would be more involved, and require a GUI update to support more views, and perhaps more metrics.

Speaking of metrics, we also believe more metrics could be added! Currently, MSE, SSIM, and feature distance can be shown for any two previously generated images. In addition, a graph is shown to let the user see spikes in changes while drawing. We think that in addition to the current metrics, other analysis should be shown. For instance, suppose we only change 100 pixels on the input image (a 10x10 square). How big of an impact did that have on the generated image? How big would the impact have been if we did that with another class? To do this, we might use a ratio of some sort, where the final result r would be a measure of how “impactful” each pixel you changed was on the output. A single pixel change resulting in the output image changing (MSE metric) by 10 would have the same r as changing 10 pixels and having the output change by 100. This would give users an insight into exactly how much they needed to do to affect the output.

In the same vein as the last idea, we’d like to measure how different the output caption is. Given that the LSTM generating that caption uses a feature vector, the feature vector might be the best way to do this, but we believe there may be better ways. Finally, and somewhat unsurprisingly, we think the “curb appeal” of the interactive page could be better. We aren’t experts in web design and had no experience with CSS, so the page leaves something to be desired. Not only that, but we aren’t using our pixels effectively! There is a lot of white space, and eyes need to do a lot of traveling to look at what they need to for analysis. A better design would make this a much more fun and easy experience.

Md. Zakir Hossain, Ferdous Sohel, Mohd Fairuz Shiratuddin, and Hamid Laga. 2018. A ComprehensiveSurvey of Deep Learning for Image Captioning. https://arxiv.org/pdf/1810.04020.pdf

Raffaella Bernardi, Ruket Cakici, Desmond Elliott, Aykut Erdem, Erkut Erdem, Nazli Ikizler-Cinbis, Frank Keller, Adrian Muscat, and Barbara Plank. 2016. Automatic description generation from images: a survey of models, datasets, and evaluation measures. J. Artif. Int. Res. 55, 1 (January 2016), 409–442. https://dl.acm.org/doi/10.5555/3013558.3013571

Park, Taesung and Liu, Ming-Yu and Wang, Ting-Chun and Zhu, Jun-Yan. "Semantic Image Synthesis with Spatially-Adaptive Normalization". Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2019.

This is a VISxAI project that follows this sequence of events:

- The user draws onto a canvas by selecting colors from classes. Effectively, they are drawing a segmentation map.

- The segmentation map is used as input to GAUGAN, which generates a realistic looking image from the segmentation map. The output is displayed next to the drawing on screen.

- Visual features are extracted from the generated image via DilatedResNet18.

- The extracted visual features are used as input into an image captioning network.

- The image caption is displayed on screen.

The goal is to see what changes in the input drawing cause interesting changes in the output caption. We hypothesize that small changes may make large changes in the caption prediction, especially when inserting classes that may not be related to the other surroundings in the scene (ex. inserting a "ceiling" in an outdoor scene).

This project uses python 3+ and PyTorch 1.0 for the machine learning, and flask for connecting the HTML/web-based front end with the back-end.

pip install -r requirements.txt

Navigate to https://pytorch.org/, select your configuration, and run the command instructed. For example, we used:

pip install torch===1.4.0 torchvision===0.5.0 -f https://download.pytorch.org/whl/torch_stable.html

If you're runing on a unix based system, install pycocotools with:

pip install pycocotools

Otherwise on Windows, you'll have to install it with this command:

pip install "git+https://github.com/philferriere/cocoapi.git#egg=pycocotools&subdirectory=PythonAPI"

Download the tar of the pretrained models from the Google Drive Folder, save it in 'SPADE/checkpoints/', and run

cd checkpoints

tar xvf checkpoints.tar.gz

Downlost the encoder, decoder, and vocab pickle files from ADD_LINK_HERE. Then, place the encoder.pkl file into CNN/models, the decoder.pkl into LSTM/models, and vocab.pkl into LSTM/data

After proper installation, navigate to the base folder and run

export FLASK_APP=HTML/playground.py

flask runIn the terminal, you should see proper initialization for SPADE and that ResNet properly loaded weights for net_encoder.

Then, open a browser and navigate to localhost:5000.

You can interact with the painting by clicking to draw. You can select classes to "draw" on the left side. Scroll through the list and click on the class desired. On the right, the output image will be shown, and below, the caption will be shown.

This folder is responsible for running the application via flask.

HTML/routes.pyis responsible for routing the calls properly. This serves the index page at HTML/app/index.html and also calls the python function to generate an image from a segmentation map input.HTML/app/index.htmlis loaded as a flask template, allowing flask to insert python code where necessary. When {{ }} is used, the inside is the python code to be called on load.

SPADE/generate.pydoes most of the backend work. It allows for creation of a GAUGAN object, which will load the ade20k pretrained model. Then,generate_from_seg_mapwill return a generated image (NumPy array) from an input segmentation map.SPADE/ade20k_cmap.txtholds color mapping information for the segmentation. GAUGAN takes a (256x256x1) input, but a grayscale segmentation map wouldn't be very fun to draw, and would be very difficult to differentiate similar gray colors. Therefore, we color map 0-255 grayscale to RGB. These mappings are saved in this text document, which also has the class names.

For the rest of the files and structure, please see SPADE/README.md.

CNN/extract.pyis for extracting the visual features from an input image. When this file is imported, a ResNet-18-Dilated model is loaded using the weights provided by the ADE20K authors to be used for extracting the features. The only method in the file isget_visual_featureswhich takes a (x, y, 3) RGB NumPy array and returns a (512) NumPy array that is the visual features for the provided input image.CNN/models/models.pyis whatCNN/extract.pyuses to construct the model. Specifically thebuild_encodermethod in theModelBuilderclass constructs the network and loads the pretrained weights.CNN/networks/ade20k-resnet18dilated-ppm_deepsup.pthcontains the weights used in our encoder network.