this story is from July 13, 2024

‘Climate politics began with equity and justice — we now face evasion, migration and wars’

Sunita Narain is director general of the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE). Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, she discusses the long ark of climate politics:

What are some key turning points in the global trajectory of climate politics?

■ This discussion began in 1991. Global warming came onto the world stage as an issue when the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change was being negotiated. Right at the start, there was concern about what this meant in terms of development for the Global South. The first big flashpoint came when a report was published just before the 1992 Rio Conference when the Framework Convention was being negotiated. Until then, there was a lot of disquiet in developing nations about global warming but things were still simmering — suddenly, this report basically stated the developing world was a cause of climate change. It showed data about rising methane emissions and said if you took the contribution of the developing world, it matched that of countries like the United States. Therefore, it suggested, everyone had to act.

Who started the fire? Climate politics includes the Global North criticising methane-emitting rice farming vs the South stressing consumerism (L)

That altered climate politics. In 1992, climate justice and equity were firmly on the table — as a result, the UN Framework Convention included the phrase ‘common but differentiated responsibility’. It also had a framing of the agreement which said a group of nations had created the problem — called Annex I countries — and they had to take the first steps to reduce emissions. Other parts of the world had the right to develop but to make their growth different from fossil fuel economics, they should receive money and technology supporting this.

How have things evolved since?

■ We have gone downhill. From 1992 to now, the entire effort has been to rewrite the Convention by erasing both the concept of historical emissions and money and technology transfers as a right for countries which didn’t create the problem. This is now the core of climate politics.

How does climate politics work within economies of the Global South?

■ The CSE has always advocated that just as you need climate justice between countries, you also need intra-climate equity — however, the latter cannot become an excuse to argue against climate justice at the global level. It is often said that only the rich in India cause emissions, the poor don’t, so why should climate justice apply to the entire country? This is why keeping the two discussions separate is crucial.

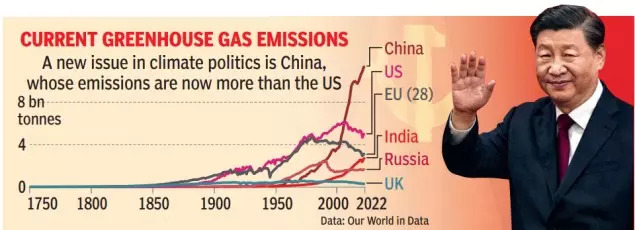

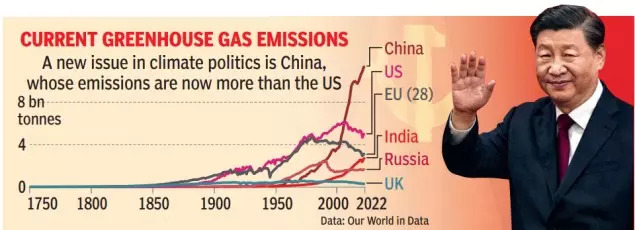

Climate justice is not a moral imperative — it is essential to get action done on climate change. Over the last few decades, due to the efforts made by some to erase the principle of justice, we have reached the worst situation possible where there isn’t a rules-based system and the emissions scenario itself has changed. Once, around seven countries, including the European Union, had caused these — now, China is also being discussed in this context. China’s emissions are over double those of the US now and by 2030, it will be equal in per capita terms. If the world had a rules-based system, as framed in 1992, a bar would be set — if a nation’s emissions rise like this, they automatically become an Annex I country and undertake reduction targets. This however was not done because the entire framing of responsibility and action was diluted. Under the Paris Agreement in 2015, it became about ‘everybody acting’.

Within India, of course, the poor are victims of climate change. Consider how a large number of women still have to cook using polluting biofuel. As they move to LPG, they will enter the fossil fuel economy. Now, suppose you had a situation where global funds for climate would go to government investments via which these women could move to the cleanest fuel possible or adopt solar technology through mini-grids, etc. We need plans like this rather than the international community trying to evade responsibility by arguing that climate justice isn’t being applied within India.

This is a year of major elections worldwide — is there adequate political discussion of climate change?

■ Global warming is definitely a mainstream issue now in terms of the extreme weather events seen worldwide. No region is being spared its effects. However, worryingly, there is also a green backlash in some places. While the environmental issue is becoming more urgent, it is also being undermined and growing marginal to many of the reasons people are voting.

This is not a uniform trend — the victory of the Labour Party over the Conservatives in the United Kingdom is very positive as Labour is much more climate-friendly. In France, the Green Party and the Left winning is also a vote for environmentally friendly policies. However, increasingly, young voters in Europe are voting for the far right. This is despite their being much more concerned than older people about climate change — yet, migration and the cost of living are taking over as issues. This is linked in part to the horrific wars the world is seeing since these are reducing the ability of governments to buffer the worst impacts on their people. We are truly in troubled times — we are in a war with nature, which we are losing, and now, physical wars, such as in Ukraine, which are draining governments and making the young insecure.

The big question is, what happens if Donald Trump returns to the White House? He’s a complete climate sceptic and a huge proponent of fossil fuels. This plays into a larger narrative, which denies the need for hard and drastic action and touts soft solutions — a few electric vehicles won’t solve this. The world’s rich are shaky over migration and rising costs — but these will only increase with environmental instability. We are entering a vicious cycle — and we need far more discussion of this.

What are some key turning points in the global trajectory of climate politics?

■ This discussion began in 1991. Global warming came onto the world stage as an issue when the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change was being negotiated. Right at the start, there was concern about what this meant in terms of development for the Global South. The first big flashpoint came when a report was published just before the 1992 Rio Conference when the Framework Convention was being negotiated. Until then, there was a lot of disquiet in developing nations about global warming but things were still simmering — suddenly, this report basically stated the developing world was a cause of climate change. It showed data about rising methane emissions and said if you took the contribution of the developing world, it matched that of countries like the United States. Therefore, it suggested, everyone had to act.

Anil Agarwal and I then worked on a report titled ‘Global Warming in an Unequal World: A Case of Environmental Colonialism’. The real sleight of hand the earlier report had done was to allocate a share of the global commons based on the contribution of emissions. Human beings emit because of fossil fuel-driven growth but nature has its own assimilative capacity to clean up through carbon sinks like the oceans. That report was saying that if the United States emits, say, 10x, then it also gets a 10x share of global sinks. We argued this was completely wrong and global sinks had to be allocated on the basis of principles. We found reallocating these on the basis of per capita changed the entire calculation.

Who started the fire? Climate politics includes the Global North criticising methane-emitting rice farming vs the South stressing consumerism (L)

That altered climate politics. In 1992, climate justice and equity were firmly on the table — as a result, the UN Framework Convention included the phrase ‘common but differentiated responsibility’. It also had a framing of the agreement which said a group of nations had created the problem — called Annex I countries — and they had to take the first steps to reduce emissions. Other parts of the world had the right to develop but to make their growth different from fossil fuel economics, they should receive money and technology supporting this.

How have things evolved since?

■ We have gone downhill. From 1992 to now, the entire effort has been to rewrite the Convention by erasing both the concept of historical emissions and money and technology transfers as a right for countries which didn’t create the problem. This is now the core of climate politics.

How does climate politics work within economies of the Global South?

■ The CSE has always advocated that just as you need climate justice between countries, you also need intra-climate equity — however, the latter cannot become an excuse to argue against climate justice at the global level. It is often said that only the rich in India cause emissions, the poor don’t, so why should climate justice apply to the entire country? This is why keeping the two discussions separate is crucial.

Climate justice is not a moral imperative — it is essential to get action done on climate change. Over the last few decades, due to the efforts made by some to erase the principle of justice, we have reached the worst situation possible where there isn’t a rules-based system and the emissions scenario itself has changed. Once, around seven countries, including the European Union, had caused these — now, China is also being discussed in this context. China’s emissions are over double those of the US now and by 2030, it will be equal in per capita terms. If the world had a rules-based system, as framed in 1992, a bar would be set — if a nation’s emissions rise like this, they automatically become an Annex I country and undertake reduction targets. This however was not done because the entire framing of responsibility and action was diluted. Under the Paris Agreement in 2015, it became about ‘everybody acting’.

Within India, of course, the poor are victims of climate change. Consider how a large number of women still have to cook using polluting biofuel. As they move to LPG, they will enter the fossil fuel economy. Now, suppose you had a situation where global funds for climate would go to government investments via which these women could move to the cleanest fuel possible or adopt solar technology through mini-grids, etc. We need plans like this rather than the international community trying to evade responsibility by arguing that climate justice isn’t being applied within India.

This is a year of major elections worldwide — is there adequate political discussion of climate change?

■ Global warming is definitely a mainstream issue now in terms of the extreme weather events seen worldwide. No region is being spared its effects. However, worryingly, there is also a green backlash in some places. While the environmental issue is becoming more urgent, it is also being undermined and growing marginal to many of the reasons people are voting.

This is not a uniform trend — the victory of the Labour Party over the Conservatives in the United Kingdom is very positive as Labour is much more climate-friendly. In France, the Green Party and the Left winning is also a vote for environmentally friendly policies. However, increasingly, young voters in Europe are voting for the far right. This is despite their being much more concerned than older people about climate change — yet, migration and the cost of living are taking over as issues. This is linked in part to the horrific wars the world is seeing since these are reducing the ability of governments to buffer the worst impacts on their people. We are truly in troubled times — we are in a war with nature, which we are losing, and now, physical wars, such as in Ukraine, which are draining governments and making the young insecure.

The big question is, what happens if Donald Trump returns to the White House? He’s a complete climate sceptic and a huge proponent of fossil fuels. This plays into a larger narrative, which denies the need for hard and drastic action and touts soft solutions — a few electric vehicles won’t solve this. The world’s rich are shaky over migration and rising costs — but these will only increase with environmental instability. We are entering a vicious cycle — and we need far more discussion of this.

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Subscribe

Start Your Daily Mornings with Times of India Newspaper! Order Now

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE