‘The race for minerals has caused global resentments — and a huge footprint on Earth’

Megan A. Black is Associate Professor of History at MIT. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, she discusses the past — and present — layering the global drive for minerals:

Which minerals have played a crucial role in shaping Earth’s economic history?

■ That entails different answers at different moments. Historically, the US bureaucracy understood minerals as vital for industrialisation — but they were a moving target. The US Interior Department, Geological Survey and the now-defunct Bureau of Mines kept shifting their attention, based on what was going on in the world.

In the late 19ᵗʰ century, for instance, gold and silver were of prime concern — that coincided with a huge expansion in coal, iron and steel, aimed to boost railroads. In the 20ᵗʰ century, war-time mobilisation and atomic energy brought minerals like cobalt, needed for industrial cutting machines, and uranium, used in enrichment to provide the chain reactions nuclear arms produced, into focus. Today, the energy story remains central — after the oil shocks of the 1970s, the US started prioritising energy beyond oil and petroleum. This included sources like low sulphur strippable coal and natural gas. Many commentators today are looking at a different set of minerals for the renewable energy transition — lithium is foremost here because of its part in battery storage and electric vehicles.

Minerals are therefore not one thing — they are many things that depend on geopolitics, national politics, economics and the environment, as evidenced by the energy transition which is making different minerals rise to the surface in the popular imagination now.

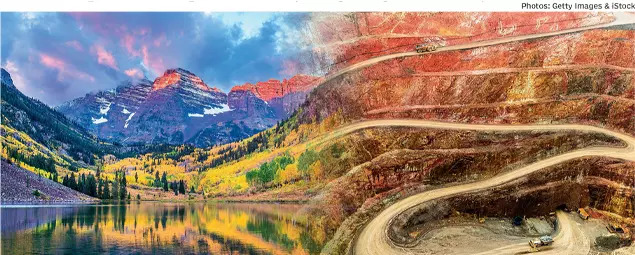

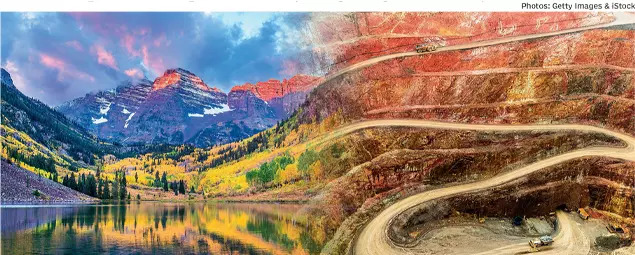

FROM PRISTINE WONDER TO THE PITS: The race for minerals fuelling economic growth has marked America’s own history, with breath-taking natural wonders like the Rocky Mountains once facing explorations for minerals like gold, silver, copper and zinc

FROM PRISTINE WONDER TO THE PITS: The race for minerals fuelling economic growth has marked America’s own history, with breath-taking natural wonders like the Rocky Mountains once facing explorations for minerals like gold, silver, copper and zinc

In America, which were some key sites of mineral riches — and who did these enrich?

■ The sites of extraction changed over time — they also tracked the altering cartography of a settler nation. For instance, the political map of America in the 1830s shows a lot of territory yet to be fully incorporated into the US. Con sider the Louisiana Purchase done between the US and France — this was the homeland of many First Nations, encompassing Georgia and the US southeast today. These lands were desired for their fertile soils — and gold reserves. These became the justification for a removal strategy termed ‘The Trail of Tears’, a coordinated policy from 1830 to 1850, forcing thousands of indigenous people to leave and move a thousand miles away to what was termed ‘Indian territory’, mostly in contemporary Oklahoma.

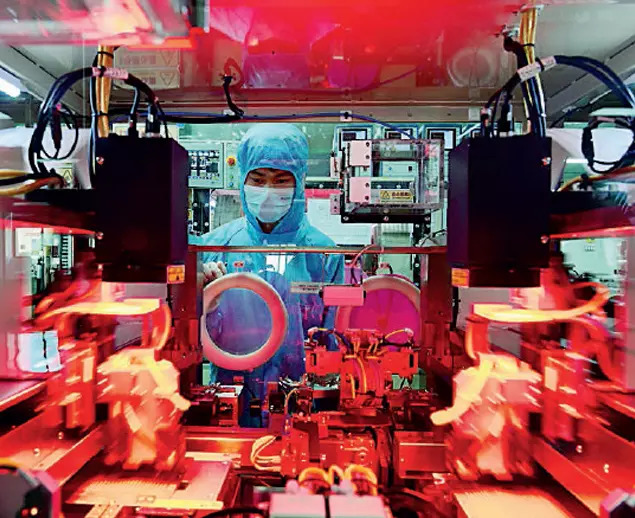

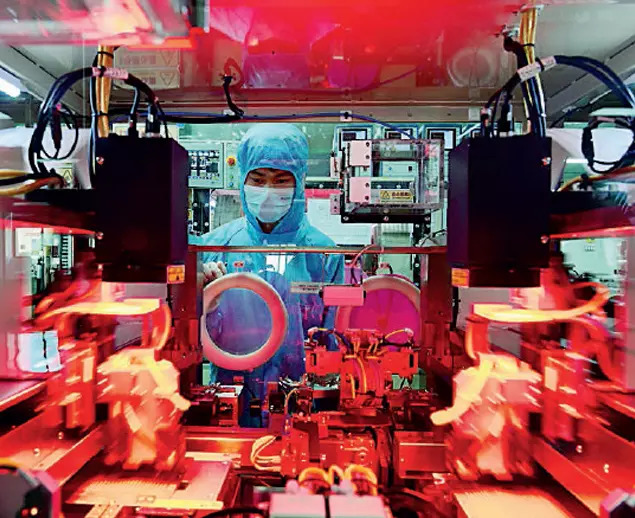

QUICK MOVER: China holds advantages in critical mineral development now (Credit: Getty Images and iStock)

QUICK MOVER: China holds advantages in critical mineral development now (Credit: Getty Images and iStock)

Certain areas also became important with the tempo of state and capitalist interests. This includes the US West in the 19th century — as American bureaucracy and corporations grew more powerful, their representatives started infiltrating the Rocky Mountains and other areas which would become sites of extraction in the gold and silver rushes. The late 19ᵗʰ century in fact revealed considerable coordination between the American government and companies. Railroad barons, for instance, depended on subsidies from the US government because this was seen as mutually beneficial, providing national security — termed as ‘protection’ against native nations outside the US project — and paths to international trade networks.

Did minerals influence global American diplomacy — and war?

■ Minerals certainly factored in a broader calculus of how the US related to the world. In the history of US foreign relations, scholars highlight geopolitical prestige, secur ing strategic trade routes and markets alongside cultural ideologies and a sense of entitlement and superiority, which were racial in orientation. Minerals were a piece of this puzzle, which helped justify an augmented American presence.

In the mid-20ᵗʰ century, the US used minerals from around the world to facilitate its arsenal in WWII. Some came from then-official US territories, like the Philippines, some, from allies in Latin America. Interestingly, the US saw its increasing mineral consumption as a problem — in 1949, a chart was made by an expert, claiming the US represented 7% of the world population, used 50% of the world’s minerals, 70% of the world’s oil and did 40% of the world’s work or manufacturing. The claim to use 50% of the world’s minerals hinted at a projection of strength different from territorial power — this was also about trade relations.

My work further studies the part international development agendas played in facilitating strategic mineral priorities for the US. The literature would not suggest the motive for international development was getting minerals in India, Colombia or Afghanistan. Certainly, there were geopolitical priori ties like securing allies — but there were also mineral interests. Fast-forward to the 1990s — American leaders were openly declaring both a raw material interest in the Persian Gulf and a humanitarian project there. Hence, activists critical of the Iraq War spoke of ‘blood for oil’ — this was a historic moment when a very important commodity moved from playing a supporting role to a lead persona.

Which technologies have been key here?

■ The history of extraction is filled with technological changes that increased capacities to mine — in the Gold Rush, hydraulic processes and using cyanide and other chemicals to release gold from the reefs it was interwoven in intensified mining. Initially, this was low-energy panning in riverbeds but now, it went to becoming a technologically-dependent — and environmentally devastating — form of extraction.

Floth flotation changed the calculus of which ores were economic because it made it easier to separate materials with chemicals — this made ores which may have only 0.5% of a desired mineral more viable. The scale expanded. Open-pit mining was another transformative technology — in the early 20th century, you carved the ground from the top rather than developing shafts underneath. Through the 20ᵗʰ century, this grew central to extractions of coal, gold and copper. Different chemical treatments also let people remove byproducts they didn’t want but there’d be tailings the size of a lake, a fluid chemical cocktail from those processes which needed dams to hold it back. Sensing technologies also play a role, with mineral industries becoming enthused by satellites and how these could get a much broader mosaic of Earth than traditional aerial surveys. The story of these technological changes shows an increasingly vast footprint on Earth.

You research American mining — today, how should we understand China’s pursuit of mineral wealth?

There are many resonances in political, economic, technological and environmental ways with the US here. Minerals fulfil security and economic priorities for nations. Julie Klinger, a geographer, has written about how China approached rare earths — 2010 was an important moment when people began talking about these being in Mongolia, etc. Klinger argues that China exploiting its own hinterland for minerals was partly about what these could do for its manufacturing — and partly meeting its political goal to control borderlands.

China’s extractive agenda spans Africa and Latin America now. The way the US criticises that or declares a need to counter China’s presence with its own is ironic. What China is doing now is not exceptional in history — the US has done all this, as have the British, French, etc., all of whom projected their presence in overseas places of mineral interest. We need to think about what the mineral rush means now for local communities, labour conditions and environmental impacts — we also need to view the mineral push as linked to climate change obstructionism. China and India point out the hypocrisy of the US demanding caps on industrialisation when it has long shown up on foreign shores, seeking fossil fuels and offloading polluting industries. One consequence of America inserting itself into the mineral landscapes of other nations has been several global resentments — and many degradations.

Which minerals have played a crucial role in shaping Earth’s economic history?

■ That entails different answers at different moments. Historically, the US bureaucracy understood minerals as vital for industrialisation — but they were a moving target. The US Interior Department, Geological Survey and the now-defunct Bureau of Mines kept shifting their attention, based on what was going on in the world.

In the late 19ᵗʰ century, for instance, gold and silver were of prime concern — that coincided with a huge expansion in coal, iron and steel, aimed to boost railroads. In the 20ᵗʰ century, war-time mobilisation and atomic energy brought minerals like cobalt, needed for industrial cutting machines, and uranium, used in enrichment to provide the chain reactions nuclear arms produced, into focus. Today, the energy story remains central — after the oil shocks of the 1970s, the US started prioritising energy beyond oil and petroleum. This included sources like low sulphur strippable coal and natural gas. Many commentators today are looking at a different set of minerals for the renewable energy transition — lithium is foremost here because of its part in battery storage and electric vehicles.

Minerals are therefore not one thing — they are many things that depend on geopolitics, national politics, economics and the environment, as evidenced by the energy transition which is making different minerals rise to the surface in the popular imagination now.

In America, which were some key sites of mineral riches — and who did these enrich?

■ The sites of extraction changed over time — they also tracked the altering cartography of a settler nation. For instance, the political map of America in the 1830s shows a lot of territory yet to be fully incorporated into the US. Con sider the Louisiana Purchase done between the US and France — this was the homeland of many First Nations, encompassing Georgia and the US southeast today. These lands were desired for their fertile soils — and gold reserves. These became the justification for a removal strategy termed ‘The Trail of Tears’, a coordinated policy from 1830 to 1850, forcing thousands of indigenous people to leave and move a thousand miles away to what was termed ‘Indian territory’, mostly in contemporary Oklahoma.

Certain areas also became important with the tempo of state and capitalist interests. This includes the US West in the 19th century — as American bureaucracy and corporations grew more powerful, their representatives started infiltrating the Rocky Mountains and other areas which would become sites of extraction in the gold and silver rushes. The late 19ᵗʰ century in fact revealed considerable coordination between the American government and companies. Railroad barons, for instance, depended on subsidies from the US government because this was seen as mutually beneficial, providing national security — termed as ‘protection’ against native nations outside the US project — and paths to international trade networks.

Did minerals influence global American diplomacy — and war?

■ Minerals certainly factored in a broader calculus of how the US related to the world. In the history of US foreign relations, scholars highlight geopolitical prestige, secur ing strategic trade routes and markets alongside cultural ideologies and a sense of entitlement and superiority, which were racial in orientation. Minerals were a piece of this puzzle, which helped justify an augmented American presence.

In the mid-20ᵗʰ century, the US used minerals from around the world to facilitate its arsenal in WWII. Some came from then-official US territories, like the Philippines, some, from allies in Latin America. Interestingly, the US saw its increasing mineral consumption as a problem — in 1949, a chart was made by an expert, claiming the US represented 7% of the world population, used 50% of the world’s minerals, 70% of the world’s oil and did 40% of the world’s work or manufacturing. The claim to use 50% of the world’s minerals hinted at a projection of strength different from territorial power — this was also about trade relations.

My work further studies the part international development agendas played in facilitating strategic mineral priorities for the US. The literature would not suggest the motive for international development was getting minerals in India, Colombia or Afghanistan. Certainly, there were geopolitical priori ties like securing allies — but there were also mineral interests. Fast-forward to the 1990s — American leaders were openly declaring both a raw material interest in the Persian Gulf and a humanitarian project there. Hence, activists critical of the Iraq War spoke of ‘blood for oil’ — this was a historic moment when a very important commodity moved from playing a supporting role to a lead persona.

Which technologies have been key here?

■ The history of extraction is filled with technological changes that increased capacities to mine — in the Gold Rush, hydraulic processes and using cyanide and other chemicals to release gold from the reefs it was interwoven in intensified mining. Initially, this was low-energy panning in riverbeds but now, it went to becoming a technologically-dependent — and environmentally devastating — form of extraction.

Floth flotation changed the calculus of which ores were economic because it made it easier to separate materials with chemicals — this made ores which may have only 0.5% of a desired mineral more viable. The scale expanded. Open-pit mining was another transformative technology — in the early 20th century, you carved the ground from the top rather than developing shafts underneath. Through the 20ᵗʰ century, this grew central to extractions of coal, gold and copper. Different chemical treatments also let people remove byproducts they didn’t want but there’d be tailings the size of a lake, a fluid chemical cocktail from those processes which needed dams to hold it back. Sensing technologies also play a role, with mineral industries becoming enthused by satellites and how these could get a much broader mosaic of Earth than traditional aerial surveys. The story of these technological changes shows an increasingly vast footprint on Earth.

You research American mining — today, how should we understand China’s pursuit of mineral wealth?

There are many resonances in political, economic, technological and environmental ways with the US here. Minerals fulfil security and economic priorities for nations. Julie Klinger, a geographer, has written about how China approached rare earths — 2010 was an important moment when people began talking about these being in Mongolia, etc. Klinger argues that China exploiting its own hinterland for minerals was partly about what these could do for its manufacturing — and partly meeting its political goal to control borderlands.

China’s extractive agenda spans Africa and Latin America now. The way the US criticises that or declares a need to counter China’s presence with its own is ironic. What China is doing now is not exceptional in history — the US has done all this, as have the British, French, etc., all of whom projected their presence in overseas places of mineral interest. We need to think about what the mineral rush means now for local communities, labour conditions and environmental impacts — we also need to view the mineral push as linked to climate change obstructionism. China and India point out the hypocrisy of the US demanding caps on industrialisation when it has long shown up on foreign shores, seeking fossil fuels and offloading polluting industries. One consequence of America inserting itself into the mineral landscapes of other nations has been several global resentments — and many degradations.

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Subscribe

Start Your Daily Mornings with Times of India Newspaper! Order Now

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE