‘The ‘resource curse’ drives petro-aggression — the US left Greenland facing Project Iceworm’

Jeff Colgan is Richard Holbrooke Professor of Political Science and International and Public Affairs at Brown University. Speaking to Srijana Mitra Das at Times Evoke, he explains oil — and conflict:

What does ‘petro-aggression’ mean?

■ ‘Petro-aggression’ is a term I coined to capture the high propensity of oil-rich states to get into wars and international conflicts. Classic examples include Iran, Iraq, Libya and Venezuela — these were all countries that had disputes with their neighbours and the United States. Such nations share problems associated with the ‘resource curse’ — countries which are blessed with abundant oil and other natural resources hope to gain economic benefits from these but instead, a series of political problems emerge. These include more corruption, a higher tendency for civil wars and a greater degree of authoritarianism.

You link fossil fuels and militarism — how is Europe, which is heavily dependent on these, faring now with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

Vladimir Putin did not come to power with a domestic revolution but he does seem to have aggressive preferences — he’s also using his oil wealth to put political and economic pressure on Europe by strategically deploying Russia’s energy resources. Prior to the war, Europe was highly dependent on oil and natural gas from Russia. Then, there were very big questions about whether Europe could find other ways to generate energy. What Europe has done quite successfully is finding alternative suppliers of natural gas and speeding up its transition to renewable energy. Power was very expensive in 2022 — but prices have come down since.

Vladimir Putin did not come to power with a domestic revolution but he does seem to have aggressive preferences — he’s also using his oil wealth to put political and economic pressure on Europe by strategically deploying Russia’s energy resources. Prior to the war, Europe was highly dependent on oil and natural gas from Russia. Then, there were very big questions about whether Europe could find other ways to generate energy. What Europe has done quite successfully is finding alternative suppliers of natural gas and speeding up its transition to renewable energy. Power was very expensive in 2022 — but prices have come down since.

Can you tell us about the Seven Sisters?

■ In the 1950s-60s, there were seven Anglo-American multinational oil companies — these were the ‘Seven Sisters’, which was a very powerful international oil cartel. They effectively controlled the supply of oil for the whole world. When they wanted to inflate prices, they suppressed supply. From their view, there was just too much oil in the world — they could see all kinds of geological reserves globally. Also, demand was much lower than today as cars, etc., were only just starting to take off. So, the Seven Sisters wielded supremacy in the field.

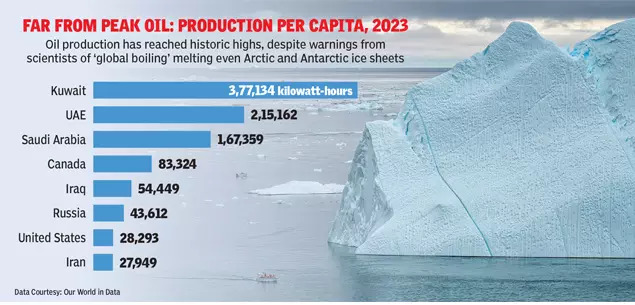

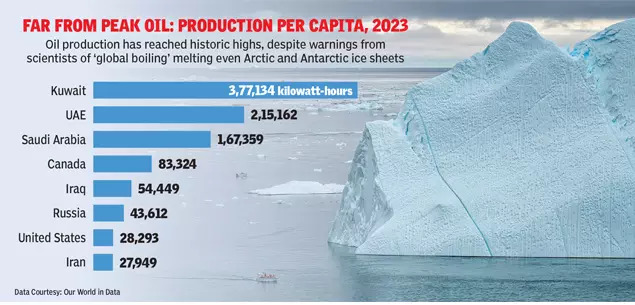

However, in the early 1970s, oil demand caught up with global supply — suddenly, there was a very tight market with supply being inadequate. That gave certain countries we now know as members of OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) an opportunity to turn the tables on these seven companies. The OPEC countries included Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Venezuela, Iraq and Iran. They wanted to sell more oil because their government revenues were based on this but they were limited by the Seven Sisters — so, they broke the cartel and ever since, they’ve operated their own.

How does OPEC act as a cartel now, both generally and regarding climate action?

■ I see OPEC mainly as a political club, rather than an economic cartel. OPEC is actually not very good at cooperating. They have regular meetings and production targets — but these are mostly ratifying what the countries would have done anyway. Only a couple of players have real market leverage because of their size — Saudi Arabia has genuine market power. Recently, OPEC+ has also grown, which includes Russia — that is big enough as well to have real impacts on oil prices. These two nations drive most of the politics shaping OPEC.

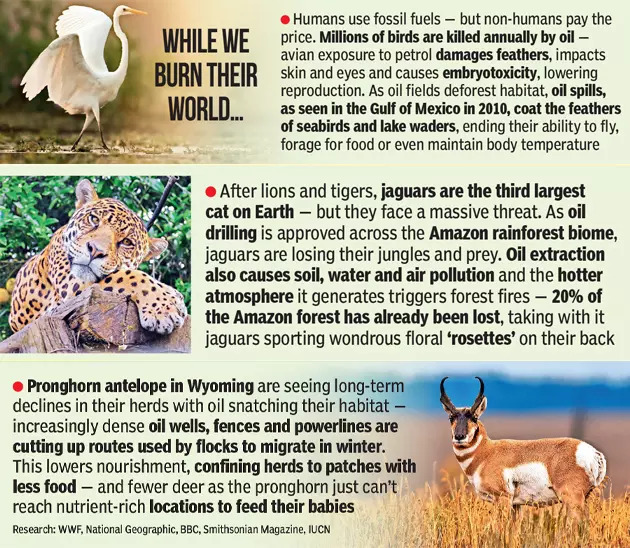

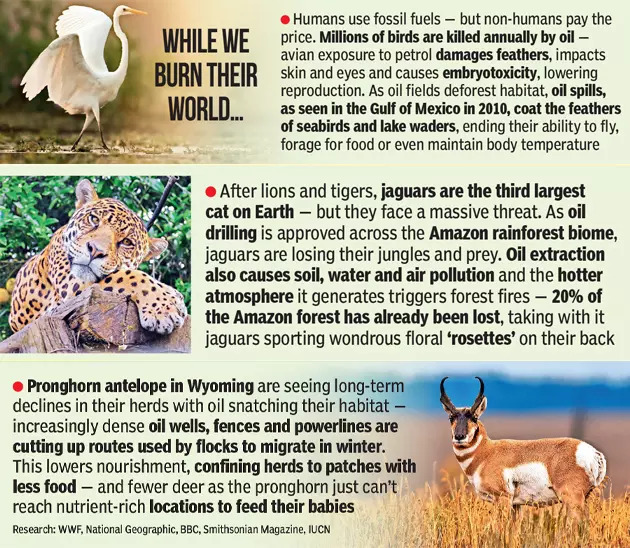

On climate change though, OPEC has been very effective in delaying or stymying progress through inter national environmental negotiations, most notably in the annual COP meetings. As oil producers, OPEC wants to continue selling, so they work very hard to prevent climate action where the demand for oil and gas are suppressed — this is very bad for the world in terms of the impacts on nature.

What would happen to big oil if the subsidies governments worldwide give to fuel were removed?

■ Oil, and all the products it allows for, like plastics, fertilisers, etc., would get more expensive. That would be uncomfortable — this is why consumers don’t want their governments to do it.

On the other hand, it is enormously wasteful for a government to be sub-sidising fossil fuels. Economically, it’s not a positive way to spend tax revenue. It is wasteful environmentally, generating over-consumption and damaging air quality, etc. And it is detrimental to health — products like cars, based on fossil fuels, cause both pollution and obesity. Relatively cheap fuel means more private transport, which reduces public transport and exercise-based modes like walking or cycling. That’s also fuelling an obesity epidemic around the world.

One argument made for fossil fuels is energy security — can renewable energies offer this to nations in the same way?

■ In fact, renewables do this better than fossil fuels. Consider western Europe and Russia in 2022 — a huge oil supplier threatens to turn off supply in the thick of winter, leading to people freezing in their homes. That is the kind of situation no politician would want. With renewables, once you have the capital equipment, like solar fields or offshore wind turbines in place, you don’t need fuel to run things. There is no way anyone can turn off the sun or wind — that makes it more secure. Suppliers of minerals or materials which compose renewable technologies could, of course, threaten not to sell you these things over time — but, if so, you have a much longer duration to react. It’s not the same thing as saying, ‘We’re going to turn off your heat tomorrow’.

While on petro-politics, can you tell us about ‘Project Iceworm’?

■ This was an absolutely crazy idea the US army had after WWII — they wanted to build a base in Greenland for upto 600 medium-range nuclear missiles that would be mounted on a train, riding 3,000 kilometres of track. This train would be buried in tunnels inside Greenland’s ice sheet — right from the start, it sounds insane, a James Bond-kind of plot, but it was real.

In the late 1950s-early 60s, the US army was very serious about this and actually built Camp Century, the central base for Project Iceworm. They brought a small nuclear reactor to Greenland to power the base. After a few years, they realised this was tech nically unfeasible and gave up — but they left a lot of nuclear wastewater at the base. They also left thousands and thousands of litres of diesel fuel — this stayed in the middle of Greenland’s ice sheet. They expected snow would cover this and it would be buried forever.

But then, climate change happened — and now, that ice is melting. The waste materials people thought would stay tens of metres below the soil surface will eventually resurface and potentially contaminate water in Greenland. Understandably, the government of Greenland would like some answers from America.

What does ‘petro-aggression’ mean?

■ ‘Petro-aggression’ is a term I coined to capture the high propensity of oil-rich states to get into wars and international conflicts. Classic examples include Iran, Iraq, Libya and Venezuela — these were all countries that had disputes with their neighbours and the United States. Such nations share problems associated with the ‘resource curse’ — countries which are blessed with abundant oil and other natural resources hope to gain economic benefits from these but instead, a series of political problems emerge. These include more corruption, a higher tendency for civil wars and a greater degree of authoritarianism.

You link fossil fuels and militarism — how is Europe, which is heavily dependent on these, faring now with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine?

■ Russia’s invasion of Ukraine looks very much like petro-aggression. Interestingly, Russia is not a typical case of this — often, with petro-aggression, we see a combination of oil wealth with revolutionary government. That generates a leader with very aggressive preferences, someone who wants to get into conflicts. This was the case with Saddam Hussein in Iraq or Muammar Gaddafi in Libya.

Can you tell us about the Seven Sisters?

■ In the 1950s-60s, there were seven Anglo-American multinational oil companies — these were the ‘Seven Sisters’, which was a very powerful international oil cartel. They effectively controlled the supply of oil for the whole world. When they wanted to inflate prices, they suppressed supply. From their view, there was just too much oil in the world — they could see all kinds of geological reserves globally. Also, demand was much lower than today as cars, etc., were only just starting to take off. So, the Seven Sisters wielded supremacy in the field.

However, in the early 1970s, oil demand caught up with global supply — suddenly, there was a very tight market with supply being inadequate. That gave certain countries we now know as members of OPEC (the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries) an opportunity to turn the tables on these seven companies. The OPEC countries included Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, Venezuela, Iraq and Iran. They wanted to sell more oil because their government revenues were based on this but they were limited by the Seven Sisters — so, they broke the cartel and ever since, they’ve operated their own.

How does OPEC act as a cartel now, both generally and regarding climate action?

■ I see OPEC mainly as a political club, rather than an economic cartel. OPEC is actually not very good at cooperating. They have regular meetings and production targets — but these are mostly ratifying what the countries would have done anyway. Only a couple of players have real market leverage because of their size — Saudi Arabia has genuine market power. Recently, OPEC+ has also grown, which includes Russia — that is big enough as well to have real impacts on oil prices. These two nations drive most of the politics shaping OPEC.

On climate change though, OPEC has been very effective in delaying or stymying progress through inter national environmental negotiations, most notably in the annual COP meetings. As oil producers, OPEC wants to continue selling, so they work very hard to prevent climate action where the demand for oil and gas are suppressed — this is very bad for the world in terms of the impacts on nature.

What would happen to big oil if the subsidies governments worldwide give to fuel were removed?

■ Oil, and all the products it allows for, like plastics, fertilisers, etc., would get more expensive. That would be uncomfortable — this is why consumers don’t want their governments to do it.

On the other hand, it is enormously wasteful for a government to be sub-sidising fossil fuels. Economically, it’s not a positive way to spend tax revenue. It is wasteful environmentally, generating over-consumption and damaging air quality, etc. And it is detrimental to health — products like cars, based on fossil fuels, cause both pollution and obesity. Relatively cheap fuel means more private transport, which reduces public transport and exercise-based modes like walking or cycling. That’s also fuelling an obesity epidemic around the world.

One argument made for fossil fuels is energy security — can renewable energies offer this to nations in the same way?

■ In fact, renewables do this better than fossil fuels. Consider western Europe and Russia in 2022 — a huge oil supplier threatens to turn off supply in the thick of winter, leading to people freezing in their homes. That is the kind of situation no politician would want. With renewables, once you have the capital equipment, like solar fields or offshore wind turbines in place, you don’t need fuel to run things. There is no way anyone can turn off the sun or wind — that makes it more secure. Suppliers of minerals or materials which compose renewable technologies could, of course, threaten not to sell you these things over time — but, if so, you have a much longer duration to react. It’s not the same thing as saying, ‘We’re going to turn off your heat tomorrow’.

While on petro-politics, can you tell us about ‘Project Iceworm’?

■ This was an absolutely crazy idea the US army had after WWII — they wanted to build a base in Greenland for upto 600 medium-range nuclear missiles that would be mounted on a train, riding 3,000 kilometres of track. This train would be buried in tunnels inside Greenland’s ice sheet — right from the start, it sounds insane, a James Bond-kind of plot, but it was real.

In the late 1950s-early 60s, the US army was very serious about this and actually built Camp Century, the central base for Project Iceworm. They brought a small nuclear reactor to Greenland to power the base. After a few years, they realised this was tech nically unfeasible and gave up — but they left a lot of nuclear wastewater at the base. They also left thousands and thousands of litres of diesel fuel — this stayed in the middle of Greenland’s ice sheet. They expected snow would cover this and it would be buried forever.

But then, climate change happened — and now, that ice is melting. The waste materials people thought would stay tens of metres below the soil surface will eventually resurface and potentially contaminate water in Greenland. Understandably, the government of Greenland would like some answers from America.

Download

The Times of India News App for Latest India News

Subscribe

Start Your Daily Mornings with Times of India Newspaper! Order Now

All Comments ()+^ Back to Top

Refrain from posting comments that are obscene, defamatory or inflammatory, and do not indulge in personal attacks, name calling or inciting hatred against any community. Help us delete comments that do not follow these guidelines by marking them offensive. Let's work together to keep the conversation civil.

HIDE