EXCLUSIVE'Everyone's on universal credit here'. As bombshell report says welfare system encourages people to claim they're too sick to work, a shocking dispatch from the disability benefits capital of the UK

Merseyside's metropolitan borough of Knowsley was once best known for being the home of Knowsley Safari Park, housed in the grounds of Knowsley Hall, the family seat of the Earl of Derby.

When the 18th earl opened the park in partnership with circus impresario Jimmy Chipperfield in 1971, the area was on the crest of a manufacturing boom. People flocked to the area to find work and the population peaked at almost 200,000. But it's been downhill ever since.

The safari park's lions, rhinos and giraffes are still in situ but tens of thousands of human residents left Knowsley as economic decline set in.

Today, it is an unemployment blackspot in which around 25,500 people, or 27 per cent of the working-age population, are considered 'economically inactive' – meaning they are neither in a job nor looking for one.

It also has the dubious distinction of being known as the 'disability benefits capital of Britain' because about 13,000 of its residents – 13.2 per cent, double the national average – are entitled to PIP (Personal Independence Payment).

This is a non-means-tested UK government benefit paid to individuals who claim to have long-term physical or mental health conditions, and more people claim it in Knowsley than any other parliamentary constituency in Britain.

Indeed, peers warned yesterday that Britain's soaring benefits bill is down to a flawed welfare system which ‘incentivises’ claimants to declare themselves long-term sick. Those eligible to claim health-related benefits could double their income by leaving the workforce, according to the scathing House of Lords report. Ministers are drawing up options to overhaul the system.

Knowsley is also ranked as Britain's obesity capital, with three-quarters of adults classed as clinically overweight.

There's no better place to examine how this depressing situation came to pass than the town of Huyton, home of Knowsley's council headquarters.

A man uses a rollator to get about in Knowsley, Merseyside

Its pedestrianised High Street is a predictably grim thoroughfare on which more shops are boarded up than open.

It is patrolled by a battalion of people on mobility scooters. In the course of a single day, I saw scores of them. And loitering next to a market stall selling odds and ends, I come across 40-year-old Jimmy, his right arm in a navy-coloured sling held together with flimsy-looking sticky tape.

He will spend his entire day strolling up and down the High Street or hovering in the cold, puffing on roll-ups and chatting aimlessly with passers-by. He tells me he has been unemployed 'for quite a long time' and has always received fortnightly £180 Universal Credit (UC) payments. 'Everyone gets Universal Credit,' he says.

When he was looking after his ill brother and sickly mother – who both passed away almost a decade ago – he also claimed a weekly £60 Carer's Allowance.

There is an alphabet soup of different benefits available to the disabled, from LCWRA (Limited Capability for Work-Related Activity) to WCA (Work Capability Assessment). But Jimmy is evasive when I ask him what other benefits he receives. He claims that he has been frequenting employment centres such as Knowsley Works and Ingeus for years in his search for work but describes them as 's***'.

He admits there are some part-time roles available but he doesn't want them because he would be paid basically the same amount he receives on UC.

It's a claim backed up by a study from the Centre For Social Justice think tank which found that people on sickness benefits could be paid as much as £23,900 a year, considerably more than someone working for the minimum wage, who receives just £20,650 after tax.

Jimmy points out another flaw in the system. 'If you're [working] part-time, you'd be paying the same amount of council tax as if someone is full-time, and that's not fair. I went to two different Citizens Advice centres and they did a calculation and said I'd only be £20 better off with part-time work than I am now. But if someone offered me a full-time job tomorrow, I would love to work.'

I ask him if he's been to the Jobcentre. 'No,' he admits, 'I only go when my job adviser wants me to come in.' Nor does he apply for jobs on his own account. 'No. They do it for me. I don't use a computer because I am dyslexic. It makes it harder.

'How can I do any more? You can only try and apply for jobs and if you don't get an interview what can you do?

'Like I said, if someone offered me a job tomorrow . . .'

Well, how many jobs have you applied for today? I ask. 'Listen, love,' he shouts, now clearly angry with me. 'I can't be applying for jobs day in and day out. You've got to have some 'me time'.'

When I ask him what he is doing today, he says: 'Well, obviously I am going to hospital later today to get this checked out,' he says, pointing at his sling, 'and then I am doing other things. All kinds of things. Maybe I will go to a friend's house or they will come to mine.'

As we chat in the street, we are interrupted by Barry Savage, 62, a friend of Jimmy's who works at Amazon. 'There are loads of jobs, mate,' he says. 'When you finish one job, you get straight back into a new job. That's how it works.'

Jimmy replies: 'Are you joking? You're joking, mate!'

'I'd be careful with that arm, mate,' Barry quips, pointing at Jimmy's sling. 'It's supposed to look broke.' Later, out of earshot of his old friend, Barry says: 'Jimmy's a liar. He wants to be on the dole, he wants to be sick. We tell him 'Jimmy, get into work' – but he wants this.

'Where he is living now, he's in [his late mother's] three-bedroom house. With the social pay, he gets it all covered; all his council tax. It frustrates me because I know he is a good worker. And he's well off because of the state benefits.'

This frustration is echoed by employment centre workers based on Huyton's High Street who are on the front line of Knowsley's worklessness crisis. They help people in Merseyside find jobs by advising them on how to write their CVs and preparing them for interviews.

A young man walks on crutches in the town of Huyton

One employee on a smoke break spoke to me candidly about the problems in Knowsley on the condition of anonymity. 'It is the worst December it has ever been for finding people jobs,' she says. 'Normally, come October, there are loads of Christmas jobs going everywhere – warehouses and shops. But it is terrible this year. Drink is a big problem around here because people have nothing to do. There are shops closing down everywhere, so people just hang out in the streets and smash things. Some people do their best and try really hard to find work. But lots of people don't want to try [to get work] because they are getting paid from the social.

'The people that get benefits go on more holidays than I do. By the time they're done adding up the child tax benefit and this benefit, that benefit and the other benefit, yeah, they are going on more holidays than I can.

'I am in full-time employment but I am getting on and can't afford to retire. Some people around here are used to not working. They are born into [on the] social families.'

When I ask if she ever sees people lying on claimant forms she gives a knowing shrug and says: 'It didn't come from me. Don't quote me!

'In other European countries you simply can't do this sort of thing. That's why everyone wants to come in. Because the Government will give it away. [In Europe] if you're on benefits you don't get a new washing machine and a new this and a new that. You get basic money to live on or you get a job.'

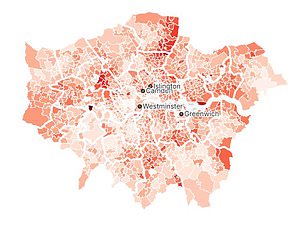

While ill health and worklessness are apparent in Knowsley, they are a growing problem nationwide. The number of working-age people deemed economically inactive has swelled to 9.2 million, according to the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Of these, a record 2.8 million are out of work as a result of 'long-term sickness', a staggering rise of 650,000 since the pandemic hit.

This is costing Britain dearly. Total spending on working-age disability and ill-health benefits has increased to a colossal £69 billion, according to a report by the Department for Work and Pensions (DWP). This figure is expected to rise to £100 billion by the end of the decade.

You might have thought that the overwhelming majority of people classed as economically inactive because of long-term health problems would be aged 50 to 65. In fact, this age group accounts for only half the claimants, with the proportion of young people on the rise as mental health diagnoses increase and more young people apply for benefits.

Just under 950,000 young people aged between 16 and 24 are now classed as 'Neets' (not in education, employment or training), according to data published by the ONS last week.

Many attribute this to the effects of the pandemic lockdowns, which left some young people feeling isolated and depressed.

But, as the Mail has reported, there is also evidence that some are gaming the system – helped by 'sickfluencers' on social media platforms such as TikTok and YouTube. These online stars have gone viral for teaching others how to fill in their benefit forms most effectively.

Tracey Smith, a TikTok personality who claims PIP for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), told her followers: 'When you're claiming PIP you need to believe you deserve to claim it because ADHD is a disability. Don't be embarrassed to talk about how you wear the same pair of knickers and clothes for days on end and how you don't get washed – all these things happen because your brain is not sending you the right signals.'

Some influencers have gone even further. YouTuber Charlie Anderson offers free 'PIP evidence templates' with answers to copy – designed to maximise the odds of a successful claim. She charges up to £950 for a four-hour, one-to-one session in which she helps her 'clients' write their PIP application forms over Zoom. 'I have only lost one case,' she brags on her YouTube channel.

The number of new PIP awards approved each month has more than doubled over the past five years from 2,200 in 2019 to 5,300.

Last month, Work and Pensions Secretary Liz Kendall published the Labour Government's long-awaited £240 million Get Britain Working white paper.

But it proved to be a damp squib, with any attempt to review or reform the benefits system postponed until at least next year – even as Britain continues to haemorrhage money.

Instead, Ms Kendall's blueprint focused on reforms to Jobcentres and the establishment of a new 'youth guarantee', which will offer jobs and training to thousands of young people not in work.

She also wants to focus on supporting people with disabilities and mental health issues by integrating the NHS and job services, with the aim of increasing employment in Britain to 80 per cent of the working-age population.

In response, Helen Whately, the shadow work and pensions secretary, accused Prime Minister Keir Starmer of dodging 'tough choices on welfare costs' and 'kicking the can down the road'. The truth, according to critics, is that generations of reliance on benefits, compounded by poor education, ill health and limited job opportunities, have left many in places such as Knowsley unwilling to join the workforce.

Those who can have moved away and pursued careers elsewhere, with the result that, in 2024, Kirkby (a town in the borough of Knowsley) is dominated by an ageing, sickly population, many of whom have spent their entire life out of work.

In Northwood – Knowsley's most deprived ward – the life expectancy for women is 76.8 years, more than six years shorter than the national average and 9.5 years shorter than women in the wealthy London borough of Kensington and Chelsea, where the average is 86.3 years.

A woman in a mobility scooter in the local shopping area

John O'Connell, chief executive of the TaxPayers' Alliance, says: 'The fact that Personal Independence Payments are not means-tested, combined with the growing pressure on GPs to sign off on applications, have stretched the system to breaking point and created a disastrous incentive structure where for too many it pays to be sick. The Government needs to look seriously at reforming the system to ensure its affordability for taxpayers.'

Residents I speak to in Kirkby candidly describe their hometown as a 's***hole'.

Many of the workless there dream of finding jobs in travel – just to get away from here.

I meet mother-of-three Julie, 57, standing under twinkling Christmas lights smoking a cigarette. She tells me she hasn't worked in more than 40 years. After she left school, she briefly had a job as a healthcare assistant but left after getting pregnant, aged 16, with her first child. Since then, she has relied on food banks, PIP and Universal Credit to get by.

'Not everyone wants to work,' she tells me when I ask her why there is such an epidemic of unemployment. 'People get comfortable with benefits and become dependent on Universal Credit.'

As I make my way down the run-down street, a local quips: 'At least someone's smiling round here.'

Tragically, this town's prevailing mood is one of depressed inertia.